A few months ago, I went to a cellar clean-out sale at one of my favorite wine shops, The Wine Bottega. While I usually find a lot of really amazing wines at the Bottega, I wasn't really expecting to find anything all that unusual this time around since most of their really weird stuff tends to move off the shelves pretty quickly and doesn't hang around long enough for clearance sales. Some of the bottles were things that Matt, one of the co-owners, had socked away, though, so there was a chance that something really cool was there to be found. I poked around for a few minutes and quickly found a bottle with an odd little orange label and the word "Abouriou" on the front. Thinking that the word sounded vaguely familiar, I asked Matt what it was and he told me it was a really obscure grape from southwestern France. It was the last bottle that they had in the shop and I eagerly took it off their hands. I recently pulled the cork on it and today I'd like to tell you a little bit about the grape itself before getting into my impressions of the wine.

Abouriou was once rather widely grown in the Lot-et-Garonne region of southwestern France, but after phylloxera swept through Europe, Abouriou nearly became extinct. It was rescued from oblivion by Numa Naugé, a grapevine breeder from Casseneuil in the Lot-et-Garonne department of France, and one of the local names for the grape, Précoce Naugé, is an homage to the person who preserved Abouriou for all of us. Naugé's story was that the vine was a local seedling discovered growing on a local castle's walls by a farmer in the 1840's. The other part of the name, Précoce, is a reference to the grape's early ripening, and in fact, Abouriou actually means "early" in the local dialect. For many years, there was a grape grown in California called Early Burgundy and it has recently been discovered that many of those vines were actually Abouriou (though some are actually Blauer Portuguesier). Only a few acres remain there today, though, and OddBacchus has a really cool interview with Steven Washuta of Old World Winery who makes wine from some of those old Abouriou vines.

In some areas of France, Abouriou is also known as Beaujolais, Gamay Beaujolais and Gamay-Saint-Laurent, but it is not related to either Gamay Noir or Pinot Noir from Burgundy, and it is a little unclear where those synonyms came from. Interestingly, Abouriou does seem to be related to both Merlot and Malbec, though the precise relationship is unclear. In 2009, a French team (citation 1) set out to try and find the parents of Merlot. They analyzed over 2300 different vines in the INRA grape repository and discovered that Merlot's parents were Cabernet Franc and an obscure grape that had no name. This unknown grape was added to the repository in 1996 when someone took cuttings from an abandoned vine growing on the slopes of Mont Garrot near Saint-Malo in Brittany. In 2004, 2005 and 2007, four more vines were found growing on arbors in front of people's homes around the area of Charentes, nearly 400 km away from the original finding. The local growers called the vine "Raisin de la Madeleine" or "Madeleina," because the vine ripened very early and was said to be ripe in time for Sainte-Madeleine's day, which is July 22. Because there are many other grapes called Madeleine or which have Madeleine in the name, these researchers decided to name this particular grape Magdeleine Noire des Charentes, after a reference in an 1847 work to a grape known as Magdeleine that was known for ripening in July, and the Charentes region where so many of the vines were found.

It turned out that Magdeleine Noire des Charentes was the mother of both Merlot and Malbec (Malbec's father is Prunelard). Furthermore, the authors discovered that Magdeleine Noire des Charentes had a parent-offspring relationship with Abouriou, though they were unable to find the other parent in the triad and so they are not sure which direction the relationship arrow points (see my post on Ciliegiolo for more details on parent/offspring relationships in grapevines). If Abouriou is the parent of Magdeleine Noire, then that means it is a grandparent to both Merlot and Malbec. If it is an offspring, then that means that Abouriou is a half sibling to those grapes (which are themselves half-siblings of one another). Because of its early ripening and its ability to resist many fungal diseases, Abouriou has been used to breed some other grapes. Most notably, it is one of the parents of Egiodola, which we'll cover shortly, and in the 1970's it was crossed with a grape called Castets in order to breed a handful of grapes in Slovakia.

Current plantings of Abouriou stand around 800 acres, which is about half of what the totals were 50 years ago. Nearly all of those plantings can be found in the district of Marmande, which is apparently most famous for the tomatoes grown there. Marmande is just up the Garonne river from Sauternes, Cadillac and Loupiac and up until the French revolution, this area was considered to be a part of Bordeaux and wines from here were sold with the Bordeaux name on them. After the French revolution, a gentleman by the name of Monsieur Lakanal was sent to the area to remove all traces of the nobility there. He also stuck his fingers in various aspects of the local wine trade and one of his decrees stated that only wines made in the department of the Gironde were permitted to use the name Bordeaux. The vineyards of the Marmandais were just over the border in the Lot-et-Garonne, and so the wine makers here suddenly found that they no longer had access to the prestigious Bordeaux name and sales immediately suffered. It wasn't until the 1950's that the region was granted VDQS status and an upgrade to AOC status has only recently been approved on the condition that one quarter of the vines in every vineyard should consist of the specific local grape varieties Syrah, Malbec, Tannat and/or Abouriou.

In his South-West France: The Wines and Winemakers (which much of the above is indebted to), Paul Strang describes Abouriou as "a rustic plant giving juice of an amazingly deep colour and big, heavy tannins, a sort of super-tannat." I pulled the cork on my 2008 Elian da Ros Abouriou ($27 on sale) to see for myself. In the glass the wine was a deep, opaque purple-ruby color. The nose was moderately intense with aromas of blackberry, black cherry, bacon, smoke, charcoal and crushed wild berries. On the palate the wine was full bodied with medium acidity and medium tannins. There were flavors of smoke, blackberry, black raspberry, bacon, wild strawberry and a touch of sweaty funk. The wine was dark and smoky with soft berryish fruits and some savory meaty flavors as well. I found it very interesting and distinctive and thought it was a reasonable value for the money. Fans of rustic French wines (those from Cahors or Madiran or made from the Fer Servadou or Duras grape variety) will definitely find a lot to like here. I'd be very interested to try one of the few California examples being produced to see how it compares with a wine from the grape's home.

CITATION

Boursiquot, JM, Lacombe, T, Laucou, V, Julliard, S, Perrin, FX, Lanier, N, Legrand, D, Meredith, C, & This, P. 2009. Parentage of Merlot and related winegrape cultivars of southwestern France: discovery of the missing link. Australian Journal of Wine and Grape Research, 15(2), pp 144-155.

A blog devoted to exploring wines made from unusual grape varieties and/or grown in unfamiliar regions all over the world. All wines are purchased by me from shops in the Boston metro area or directly from wineries that I have visited. If a reviewed bottle is a free sample, that fact is acknowledged prior to the bottle's review. I do not receive any compensation from any of the wineries, wine shops or companies that I mention on the blog.

Thursday, January 31, 2013

Monday, January 28, 2013

Inzolia/Ansonica - Sicily and Isola del Giglio, Tuscany, Italy

A few days ago, we took a look at a grape known as Garganega in the Veneto in northeastern Italy and as Grecanico Dorato in Sicily way down in southern Italy, but virtually nowhere in between. While I found that particular geographical situation odd, it is certainly not unique. Today's grape, for example, is found primarily in Sicily, but is also fairly well represented in Tuscany and has been known in each of those areas for over 300 years, but aside from a few stray vines in Sardinia, Campania and Lazio, it isn't really grown anywhere else. In Sicily, that grape is known as Inzolia while in Tuscany, it is known as Ansonica and today I'd like to take a closer look at it and its journey.

As mentioned above, Inzolia/Ansonica are first mentioned definitively in the literature around the 16th or 17th centuries. I say definitively because the ancient Roman writer Pliny the Elder mentions a grape called Irziola in his Naturalis Historia, which some have taken to be the first mention of Inzolia in print, but aside from their similar sounds, there is no evidence that indicates that Pliny was talking about the grape we know as Inzolia today. In Sicily, Inzolia has historically been found mainly on the western end of the island where it is has been valued as an ingredient, along with Grillo, in high-end Marsala production. As the production of high-end Marsala has fallen, Inzolia has given way to Catarratto, which is more widely used for low-end Marsala production. Inzolia is still relatively widely planted, though, as current Sicilian acreage stands at around 19,000 acres. As table wine production has taken off in Sicily over the past few decades, more and more of the existing Inzolia plantings have been used for that purpose as well.

In Tuscany, the grape is known as Ansonica and is planted mainly along the coast and on some of the nearby islands of the Tuscan archipelago. The most famous of these seven islands is Elba, where Napoleon was banished in 1814, and while Ansonica is grown there, the island we're most concerned with is called Giglio. Giglio is a small (about 1.36 square miles), mountainous island made primarily of granite and located about 10 miles from the Tuscan shore. It has been inhabited since the Stone Age and has been ruled over by the Etruscans, Greeks, Romans and Florentines among others. At various times throughout history, the island has been completely abandoned as invading forces deported the native population, but it has always been resettled eventually. Grapes have been grown on this island since at least the 6th Century BC, and today, Ansonica is the mostly widely planted grape there.

Despite their geographical distance, ampelographers have long suspected that Inzolia and Ansonica were the same grape and the Italian authorities have recognized them as the same for many years. In 1999, the first DNA evidence started coming in which validated this particular hypothesis. An Italian team used AFLP markers, which are a little bit different from the microsatellite markers primarily used today, to show that the Ansonica from Giglio was most closely related to Ansonica from the Tuscan mainlaind, Inzolia from Sicily, Roditis from Greece, Airén from Spain and Clairette from France. While these results are interesting, we do have to take them with a grain of salt. AFLP analysis is looking at DNA sites throughout a sample's genome, which means that it can be more precise than microsatellite analysis, but that precision isn't necessarily a good thing. If you're looking for a murderer, then you want to be as precise as possible, but when you're dealing with families of plants that are subject to genetic mutation over time, that precision can indicate differences in two plants that you would otherwise consider to be identical.* Clonal variants can show up in AFLP analysis as different varieties, as can geographically disparate populations that shared a common ancestor hundreds of years ago, but which have been evolving separately from one another ever since. This is the case with Inzolia and Ansonica, and this AFLP analysis was able to show that there were differences not only between Tuscan Ansonica and Sicilian Inzolia, but also between Ansonica from Giglio and Ansonica from Tuscany. The two Ansonicas were closer to one another than to Inzolia from Sicily and the Tuscan Ansonica was closer to the Sicilian Inzolia than the Giglio Ansonica was, which would indicate that the grape likely came from Sicily to Tuscany and then to Giglio.

I mentioned above that this study also found similarities between Inzolia/Ansonica and Roditis, Airén and Clairette, and this probably needs a bit of explanation as well. Many genetic studies compare large groups of grapes from specific geographic regions in order to see how similar they are to one another genetically. The theory is that grapes from a certain region have likely been together a very long time and are probably distantly related to one another in ways that are too complicated to tease out with pedigree analysis. When testing a large pool of grapes, the scientists look to see which grapes have the most DNA in common with one another and then hypothesize that these grapes are then more closely related to one another than to the other grapes in the study. The main problem in interpreting the results is that you are limited by the number and the variety of grapes in a study. The results are really only telling you that these grapes are more like each other than the other grapes in the study, which can be problematic if you've chosen your samples poorly. Imagine a study like this done with human beings where you're Italian and your family has lived in a small village for hundreds of years. The researchers select you and a handful of people from your town and compare them with another group from the mountains of Tibet. The study should show that you are more closely related to the people from your village than the villagers of Tibet. Now imagine that the study took you, one person from the village in Tibet, and a pack of chimpanzees. Suddenly you and the Tibetan villager look a lot more closely related.

The point is that these relatedness studies can be useful, but they can also be misleading. The group above sampled a very high number of Greek grapes along with a handful of grapes from a whole bunch of different regions all over the world. They tested very few Sicilian or Tuscan varieties, which one would expect to be more closely related, and so the results may be a little skewed. They interpreted their results as showing that Inzolia likely came from Greece, due to its relatedness to Roditis, into Sicily before moving to Tuscany and then to Giglio. In Wine Grapes, Vouillamoz points to a 2010 study (citation 1) where another Italian team analyzed 82 different Sicilian grapes to see how closely they were related as refutation of the study above. They found that Inzolia was mostly closely related to a few other varieties with Inzolia in the name (but which are separate varieties) such as Inzolia Imperiale and Inzolia Nera (which is not a red-berried mutation of Inzolia at all, but rather a separate variety). Further, this group also had similarities with Coda di Volpe, Grecanico, Frappato, Carricante and Nerello Mascalese among others. Vouillamoz claims that the relatedness of Inzolia to these other Sicilian grapes indicates that it is likely from Sicily and not from Greece. Since this particular study did not include any Greek grape varieties, it seems difficult to compare the results from the different studies and come to that kind of conclusion. Both studies do seem to indicate that Inzolia came from Sicily to Tuscany, but whether it is native to Sicily or whether its ancestors or Greek seems to still be an open question.

I was able to try two different wines, one from Sicily and one from Giglio, made from the Inzolia/Ansonica grape. The first was the 2009 Ansonaco from Familia Carfagna, which I picked up for around $50 from my friends at the Wine Bottega (though I have recently seen it available at Curtis Liquors as well). In the glass the wine was a medium bronze gold color. The nose was intense with aromas of ripe red apples, toasted nuts, apple cider, poached pear, brown sugar, dried apple and abundant autumn spice. On the palate the wine was medium bodied with fairly acidity. There were flavors of dried apricot, red apple, apple cider, toasted almonds, autumn spice and dried leaves. I would have sworn that this wine saw some skin contact, but this website seems to indicate no maceration. I thought this was a really gorgeous wine that was an absolute pleasure to drink. It should be drunk at cellar or room temperature, as the cold really blunts the aromas and flavors. It is a bit pricey but I thought it was worth every penny. You probably could pair this with some food, but I really just enjoyed it on its own.

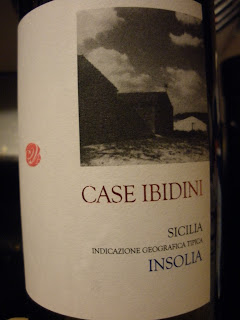

The second wine that I tried was the 2010 Case Ibidni Inzolia from Sicily, which I picked up from my friends at the Wine Bottega for around $12. In the glass the wine was a medium lemon yellow color. The nose was moderately intense with aromas of ripe white pear, green melon, ripe apple and something vaguely tropical. On the palate the wine was on the lighter side of medium with medium acidity. There were flavors of ripe, round white pear and red apple along with a touch of mild pineapple and banana. Inzolia does have a tendency to get flabby if not picked early enough, and I think that these grapes maybe hung on the vine a little too long. It had some of those flat fruit-cocktail kinds of flavors going on and really wasn't my thing.

Reader and frequent commenter WineKnurd was able to try a more recent vintage (2011) of this wine which he picked up from his friends at Wine Authorities in Durham, North Carolina. His tasting note reads:

"100% Insolia from Sicily, 12.5% abv with a slight spritz in the glass on first pour. Classic Italian white wine nose full of wet stone and minerals backed with notes of fresh cut granny smith apple and some hints of cantaloupe rind. The palate was lighter and less intense than I was expecting based on the nose and the wine in general had lower acidity than what I was expecting for an Italian white. Up front there are flavors of sour apple and melon rind but somewhere along the mid-palate it thins out and finishes weak. My guess is that this needs to be consumed as fresh as possible in Sicily, not a year behind in the USA. At $12.99 it doesn't break the bank but this is money better spent elsewhere."

As mentioned above, Inzolia/Ansonica are first mentioned definitively in the literature around the 16th or 17th centuries. I say definitively because the ancient Roman writer Pliny the Elder mentions a grape called Irziola in his Naturalis Historia, which some have taken to be the first mention of Inzolia in print, but aside from their similar sounds, there is no evidence that indicates that Pliny was talking about the grape we know as Inzolia today. In Sicily, Inzolia has historically been found mainly on the western end of the island where it is has been valued as an ingredient, along with Grillo, in high-end Marsala production. As the production of high-end Marsala has fallen, Inzolia has given way to Catarratto, which is more widely used for low-end Marsala production. Inzolia is still relatively widely planted, though, as current Sicilian acreage stands at around 19,000 acres. As table wine production has taken off in Sicily over the past few decades, more and more of the existing Inzolia plantings have been used for that purpose as well.

In Tuscany, the grape is known as Ansonica and is planted mainly along the coast and on some of the nearby islands of the Tuscan archipelago. The most famous of these seven islands is Elba, where Napoleon was banished in 1814, and while Ansonica is grown there, the island we're most concerned with is called Giglio. Giglio is a small (about 1.36 square miles), mountainous island made primarily of granite and located about 10 miles from the Tuscan shore. It has been inhabited since the Stone Age and has been ruled over by the Etruscans, Greeks, Romans and Florentines among others. At various times throughout history, the island has been completely abandoned as invading forces deported the native population, but it has always been resettled eventually. Grapes have been grown on this island since at least the 6th Century BC, and today, Ansonica is the mostly widely planted grape there.

Despite their geographical distance, ampelographers have long suspected that Inzolia and Ansonica were the same grape and the Italian authorities have recognized them as the same for many years. In 1999, the first DNA evidence started coming in which validated this particular hypothesis. An Italian team used AFLP markers, which are a little bit different from the microsatellite markers primarily used today, to show that the Ansonica from Giglio was most closely related to Ansonica from the Tuscan mainlaind, Inzolia from Sicily, Roditis from Greece, Airén from Spain and Clairette from France. While these results are interesting, we do have to take them with a grain of salt. AFLP analysis is looking at DNA sites throughout a sample's genome, which means that it can be more precise than microsatellite analysis, but that precision isn't necessarily a good thing. If you're looking for a murderer, then you want to be as precise as possible, but when you're dealing with families of plants that are subject to genetic mutation over time, that precision can indicate differences in two plants that you would otherwise consider to be identical.* Clonal variants can show up in AFLP analysis as different varieties, as can geographically disparate populations that shared a common ancestor hundreds of years ago, but which have been evolving separately from one another ever since. This is the case with Inzolia and Ansonica, and this AFLP analysis was able to show that there were differences not only between Tuscan Ansonica and Sicilian Inzolia, but also between Ansonica from Giglio and Ansonica from Tuscany. The two Ansonicas were closer to one another than to Inzolia from Sicily and the Tuscan Ansonica was closer to the Sicilian Inzolia than the Giglio Ansonica was, which would indicate that the grape likely came from Sicily to Tuscany and then to Giglio.

I mentioned above that this study also found similarities between Inzolia/Ansonica and Roditis, Airén and Clairette, and this probably needs a bit of explanation as well. Many genetic studies compare large groups of grapes from specific geographic regions in order to see how similar they are to one another genetically. The theory is that grapes from a certain region have likely been together a very long time and are probably distantly related to one another in ways that are too complicated to tease out with pedigree analysis. When testing a large pool of grapes, the scientists look to see which grapes have the most DNA in common with one another and then hypothesize that these grapes are then more closely related to one another than to the other grapes in the study. The main problem in interpreting the results is that you are limited by the number and the variety of grapes in a study. The results are really only telling you that these grapes are more like each other than the other grapes in the study, which can be problematic if you've chosen your samples poorly. Imagine a study like this done with human beings where you're Italian and your family has lived in a small village for hundreds of years. The researchers select you and a handful of people from your town and compare them with another group from the mountains of Tibet. The study should show that you are more closely related to the people from your village than the villagers of Tibet. Now imagine that the study took you, one person from the village in Tibet, and a pack of chimpanzees. Suddenly you and the Tibetan villager look a lot more closely related.

The point is that these relatedness studies can be useful, but they can also be misleading. The group above sampled a very high number of Greek grapes along with a handful of grapes from a whole bunch of different regions all over the world. They tested very few Sicilian or Tuscan varieties, which one would expect to be more closely related, and so the results may be a little skewed. They interpreted their results as showing that Inzolia likely came from Greece, due to its relatedness to Roditis, into Sicily before moving to Tuscany and then to Giglio. In Wine Grapes, Vouillamoz points to a 2010 study (citation 1) where another Italian team analyzed 82 different Sicilian grapes to see how closely they were related as refutation of the study above. They found that Inzolia was mostly closely related to a few other varieties with Inzolia in the name (but which are separate varieties) such as Inzolia Imperiale and Inzolia Nera (which is not a red-berried mutation of Inzolia at all, but rather a separate variety). Further, this group also had similarities with Coda di Volpe, Grecanico, Frappato, Carricante and Nerello Mascalese among others. Vouillamoz claims that the relatedness of Inzolia to these other Sicilian grapes indicates that it is likely from Sicily and not from Greece. Since this particular study did not include any Greek grape varieties, it seems difficult to compare the results from the different studies and come to that kind of conclusion. Both studies do seem to indicate that Inzolia came from Sicily to Tuscany, but whether it is native to Sicily or whether its ancestors or Greek seems to still be an open question.

I was able to try two different wines, one from Sicily and one from Giglio, made from the Inzolia/Ansonica grape. The first was the 2009 Ansonaco from Familia Carfagna, which I picked up for around $50 from my friends at the Wine Bottega (though I have recently seen it available at Curtis Liquors as well). In the glass the wine was a medium bronze gold color. The nose was intense with aromas of ripe red apples, toasted nuts, apple cider, poached pear, brown sugar, dried apple and abundant autumn spice. On the palate the wine was medium bodied with fairly acidity. There were flavors of dried apricot, red apple, apple cider, toasted almonds, autumn spice and dried leaves. I would have sworn that this wine saw some skin contact, but this website seems to indicate no maceration. I thought this was a really gorgeous wine that was an absolute pleasure to drink. It should be drunk at cellar or room temperature, as the cold really blunts the aromas and flavors. It is a bit pricey but I thought it was worth every penny. You probably could pair this with some food, but I really just enjoyed it on its own.

The second wine that I tried was the 2010 Case Ibidni Inzolia from Sicily, which I picked up from my friends at the Wine Bottega for around $12. In the glass the wine was a medium lemon yellow color. The nose was moderately intense with aromas of ripe white pear, green melon, ripe apple and something vaguely tropical. On the palate the wine was on the lighter side of medium with medium acidity. There were flavors of ripe, round white pear and red apple along with a touch of mild pineapple and banana. Inzolia does have a tendency to get flabby if not picked early enough, and I think that these grapes maybe hung on the vine a little too long. It had some of those flat fruit-cocktail kinds of flavors going on and really wasn't my thing.

Reader and frequent commenter WineKnurd was able to try a more recent vintage (2011) of this wine which he picked up from his friends at Wine Authorities in Durham, North Carolina. His tasting note reads:

"100% Insolia from Sicily, 12.5% abv with a slight spritz in the glass on first pour. Classic Italian white wine nose full of wet stone and minerals backed with notes of fresh cut granny smith apple and some hints of cantaloupe rind. The palate was lighter and less intense than I was expecting based on the nose and the wine in general had lower acidity than what I was expecting for an Italian white. Up front there are flavors of sour apple and melon rind but somewhere along the mid-palate it thins out and finishes weak. My guess is that this needs to be consumed as fresh as possible in Sicily, not a year behind in the USA. At $12.99 it doesn't break the bank but this is money better spent elsewhere."

CITATION

1) Carimi, F, Mercati, F, Abbate, L, & Sunseri, F. 2010. Microsatellite analyses for evaluation of genetic diversity among Sicilian grapevine cultivars. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 57(5): pp 703-719.

*It really seems to be taken for granted that Inzolia and Ansonica are genetically identical, but I actually was not able to find any studies that specifically prove the synonymy. I checked the microsatellite profile data in the VIVC with the data given for Inzolia in Citation 1 and found that the adjusted values matched at all six sites, so that's good enough for me.

Labels:

Ansonica,

Inzolia,

Isola del Giglio,

Italy,

SCIENCE,

Sicily,

Tuscany,

White Wine

Friday, January 25, 2013

Mtsvane Kakhuri - Kakheti, Georgia

In my prior two posts featuring wines with a splash of Mtsvane, I was under the impression that there was a single Mtsvane grape and that the references to Mtsvane in each of the two wines were references to that grape. It turns out that there are many grapes with the word Mtsvane in their names because in Georgian, Mtsvane just means "green." Many grapes are called Mtsvane Something, and typically the Something part of the name has to do with where the grape is from (or thought to be from). Mtsvane Goruli (or Goruli Mtsvane) means "green from Gori," which is a town in the Kartli region in the Caucasus mountains of south-central Georgia. This is the grape that was used in the Bagrationi sparkling wine that I wrote about in 2011. Today's grape is called Mtsvane Kakhuri, which means "green from Kakheti" since it is thought to be native to the Kakheti region of Georgia. This is the grape that was also in the Tsinandali wine I wrote about way back in 2010. Confusingly, both grapes are generally known and generally labeled merely as Mtsvane so to figure out which one you're dealing with, you have to know where in Georgia your wine is from.

There are many other Mtsvane Something vines (the VIVC has around a dozen listed), but Goruli and Kakhuri are the most common. Of those two, Kakhuri is more widely planted with nearly 600 acres devoted to it as of 2004. Mtsvane Kakhuri is also grown to some extent in Armenia, Moldova, Russia and the Ukraine, but not really anywhere else. Georgia's wine making history is thought to be older than any other country's, and many grapes currently grown there are said to have very ancient roots, but these claims are often difficult to back up. Nearly all of the evidence for early wine making is archaeological and it gives little idea as to exactly what grapes may have been used for those ancient wines. Further, as we've noted above, names like Mtsvane are very common and it is unclear which Mtsvane may be referenced when there are are textual sources available. Finally, Georgia has had a complicated relationship with Russia throughout its history and was stuck behind the Iron Curtain for much of the 20th Century. This relationship may have corrupted or destroyed some records as well.

The wine that I was able to try was the NV (though it was possibly from 2009, according to a comment below from the wine's importer) Telavi Wine Cellar "Marani" Mtsvane from the Kakheti region of Georgia. This bottle set me back about $12. In the glass the wine was a silvery lemon color. The nose was somewhat reserved with aromas of apricot, pear, and green apple with a weird chemical or metallic kind of smell. On the palate the wine was medium bodied with fairly low to low acidity. There were broad flavors of pear, golden apple, white peach and lemon peel/lemon water. The flavors were pretty washed out and when you coupled that with the fairly low acidity, you end up with a wine that's not a whole lot of fun to drink. While there are a lot of good wines coming out of Georgia, there's still also a lot of lackluster and sometimes straight up bad wines coming out as well and it's difficult to know what you're getting yourself into when you're trying something new. This isn't a bad wine, but merely an average one that I have a hard time imagining a place for at my table or in my cellar.

Tuesday, January 22, 2013

Manzoni Bianco (Incrocio Manzoni 6.0.13) - Benaco Bresciano, Lombardy, and Vignetti Delle Dolomiti, Trentino, Italy

Most countries that have an established wine industry also tend to have oenology and viticulture research programs which have a number of different aims. In general, these programs are responsible for carrying out research to try and improve the wine quality within a given country. At one time, grape breeding was a big part of this particular mission. Many of the French hybrid grapes were created in an effort to combat the phylloxera louse, while many of the German crossings (such as Sheurebe, Kerner and Dornfelder, among others) were created in an effort to match individual grapes with various aspects of the difficult German climate. In the United States, much of the work done in grape breeding was done by Harold Olmo at UC Davis (who created Symphony, Emerald Riesling and Early Muscat), though the University of Cornell has released a few grapes (like Chardonel) as have some private breeders like Elmer Swenson (who created St. Croix). The one huge wine power who seems to be missing in this story is Italy.

Italy does have research institutions throughout the country devoted to grape research, but grape breeding has never really been their focus. There are specific Italian crosses, but they aren't as well known or as widely spread as those efforts from other countries for a variety of reasons. The primary reason is that Italy is embarrassingly rich in native grape varieties with several hundred approved for use and an estimated several thousand actually spread throughout the country. Another big reason for the lack of Italian crossings/hybrids is that Italy does not have the same challenging climates as countries like Germany or the USA and so there wasn't and isn't any real need to develop new varieties that could survive. Furthermore, even some of the more difficult climates in Italy have been growing grapes for hundreds of years that are native to the area and thus already adapted to the local weather systems. In short, why would you need to create any new grapes when you have so many varieties close at hand and when you have climates that are essentially tailor-made for the growth of vines?

One of things that makes us human, though, is our inability to accept the limitations that nature has laid upon us. Yes, we have many excellent grapes that grow well in our climates, but surely we can do better? It was in that spirit that Professor Luigi Manzoni began his work in grape breeding at the Viticulture and Oenology School of Conegliano in the Veneto region of Italy. Manzoni, who lived from 1888 until 1968, was involved in many different kinds of research on the vine, and one of the areas he was experimenting in was grape breeding. He was not the only grape breeder active in Italy (see also Bruno Bruni, creator of Incrocio Bruni 54), but he was perhaps the most successful. His aim was to try and create new varieties for the Veneto that were of higher quality than those already being cultivated, but which would also yield more prolifically and be more disease resistant. Manzoni was not the only grape breeder active in Italy (see also Bruno Bruni, creator of Incrocio Bruni 54), but he was perhaps the most successful.

Manzoni created many different crossings throughout his career, but as with most grape breeders, only a few have had any lasting importance. He created Manzoni Moscato by crossing Moscato di Amburgo and Raboso, Manzoni Rosa (or Manzoni 1.50) by crossing Trebbiano and Traminer, and Incrocio Terzi N.1 by crossing Barbera with Cabernet Franc. Two of his most famous red grapes are known as Incrocio Manzoni 2-14 and Incrocio Manzoni 2-15, and both are supposedly made by crossing Glera and Cabernet Sauvignon, but a recent study (citation 1) seems to indicate that 2-15 is actually a crossing between Mathiasz Janosne (Mathiasz 210) and Kövidinka. Many of these grapes are grown in commercial quantities in northeastern Italy, but just barely.

The most famous Manzoni creation, though, is almost certainly Manzoni Bianco, or Manzoni 6.0.13. Manzoni created this grape at some point in the early 1930's supposedly by crossing Pinot Bianco and Riesling. Wine Grapes indicates that this parentage was disputed by a few Italian authors who believed that the grape was actually a Chardonnay and Riesling cross, but Vouillamoz assures us that his DNA research shows that the given pedigree is correct (I do not have access either to the original dispute or to Vouillamoz's DNA data, so I suppose I'll take his word for it). You may be surprised to learn that Manzoni Bianco is currently the 13th most widely planted grape in all of Italy with nearly 24,000 acres devoted to it. It is permitted in a few DOCs in the Veneto and in Trentino, but most of the plantings are actually further south in Calabria, Puglia and Molise where it is likely used for bulk wine production.

I was able to track down two wines featuring the Manzoni Bianco grape. The first was the 2009 Pratello "Lieti Conversari," which I picked up from my friends at the Spirited Gourmet for around $25. This wine is 100% Manzoni Bianco from the Brescia region of Lombardy. The grapes for this wine are hand harvested and 80% are fermented in stainless steel while 20% are fermented in oak barrels for 3-4 months (it is unclear whether it is new oak or not, but the wine didn't taste oaky to me at all and I would have guessed this saw 100% stainless steel). In the glass the wine was a medium lemon gold color. The nose was moderately intense with aromas of white peach, green apple, pear and grapefruit. On the palate the wine was on the lighter side of medium with fairly high acidity. There were flavors of grapefruit, lime, racy green apple, pear and white peach. It felt like there was still a slight prickle of CO2 to the wine as well, but since it didn't really dissipate, it was probably just an effect of the acidity. It was bright and zippy, despite the fact that it clocked in at a pretty hefty 14% alcohol. I found it lithe, vibrant and very enjoyable overall. Fans of snappy high acid whites will find a lot to like here, but be careful as it wears the 14% alcohol well and it can sneak up on you.

The second wine that I tried was the 2010 "Fontanasanta" from Elisabetta Foradori, which I picked up for around $28 from my friends at the Wine Bottega. This wine is 100% Manzoni Bianco from the hills above Trentino that is left in contact with its skins after crushing for about a week in large, egg shaped cement containers (there's a biodynamic reason for this that I don't really buy, so I'll just leave it at that). The wine is then aged for 12 months in acacia casks prior to bottling. In the glass the wine was a medium bronze gold color. The nose was moderately intense with aromas of pear, toasted almond, honey, red apple and lemon peel. On the palate the wine was medium bodied with medium acidity. There were flavors of ripe apple, pear, almond, honeysuckle flower, pineapple and a touch of apple cider. It's difficult to imagine two wines more different from one another than the two I tried for this tasting. The Foradori was deep, rich and honeyed with lovely cidery notes and bit of oxidative tang. What it lacked in vibrancy and freshness, it made up for in depth and complexity. It's difficult to say which wine is "better" since both were clearly made to be such different things. In the spring and summer months, I'd probably reach for the Pratello, but in the cooler fall and winter, I'd definitely go for the Foradori. Both are very good, very interesting wines that really show what Incrocio Manzoni is capable of in careful hands.

CITATIONS

1) Lacombe, T., Boursiquot, J.M., Laucou, V., Di Vecchi-Staraz, M., Peros, J.P., & This, P. 2012. Large scale parentage analysis in an extended set of grapevine cultivars (Vitis vinifera L.). Theoretical and Applied Genetics. In press.

Italy does have research institutions throughout the country devoted to grape research, but grape breeding has never really been their focus. There are specific Italian crosses, but they aren't as well known or as widely spread as those efforts from other countries for a variety of reasons. The primary reason is that Italy is embarrassingly rich in native grape varieties with several hundred approved for use and an estimated several thousand actually spread throughout the country. Another big reason for the lack of Italian crossings/hybrids is that Italy does not have the same challenging climates as countries like Germany or the USA and so there wasn't and isn't any real need to develop new varieties that could survive. Furthermore, even some of the more difficult climates in Italy have been growing grapes for hundreds of years that are native to the area and thus already adapted to the local weather systems. In short, why would you need to create any new grapes when you have so many varieties close at hand and when you have climates that are essentially tailor-made for the growth of vines?

One of things that makes us human, though, is our inability to accept the limitations that nature has laid upon us. Yes, we have many excellent grapes that grow well in our climates, but surely we can do better? It was in that spirit that Professor Luigi Manzoni began his work in grape breeding at the Viticulture and Oenology School of Conegliano in the Veneto region of Italy. Manzoni, who lived from 1888 until 1968, was involved in many different kinds of research on the vine, and one of the areas he was experimenting in was grape breeding. He was not the only grape breeder active in Italy (see also Bruno Bruni, creator of Incrocio Bruni 54), but he was perhaps the most successful. His aim was to try and create new varieties for the Veneto that were of higher quality than those already being cultivated, but which would also yield more prolifically and be more disease resistant. Manzoni was not the only grape breeder active in Italy (see also Bruno Bruni, creator of Incrocio Bruni 54), but he was perhaps the most successful.

Manzoni created many different crossings throughout his career, but as with most grape breeders, only a few have had any lasting importance. He created Manzoni Moscato by crossing Moscato di Amburgo and Raboso, Manzoni Rosa (or Manzoni 1.50) by crossing Trebbiano and Traminer, and Incrocio Terzi N.1 by crossing Barbera with Cabernet Franc. Two of his most famous red grapes are known as Incrocio Manzoni 2-14 and Incrocio Manzoni 2-15, and both are supposedly made by crossing Glera and Cabernet Sauvignon, but a recent study (citation 1) seems to indicate that 2-15 is actually a crossing between Mathiasz Janosne (Mathiasz 210) and Kövidinka. Many of these grapes are grown in commercial quantities in northeastern Italy, but just barely.

The most famous Manzoni creation, though, is almost certainly Manzoni Bianco, or Manzoni 6.0.13. Manzoni created this grape at some point in the early 1930's supposedly by crossing Pinot Bianco and Riesling. Wine Grapes indicates that this parentage was disputed by a few Italian authors who believed that the grape was actually a Chardonnay and Riesling cross, but Vouillamoz assures us that his DNA research shows that the given pedigree is correct (I do not have access either to the original dispute or to Vouillamoz's DNA data, so I suppose I'll take his word for it). You may be surprised to learn that Manzoni Bianco is currently the 13th most widely planted grape in all of Italy with nearly 24,000 acres devoted to it. It is permitted in a few DOCs in the Veneto and in Trentino, but most of the plantings are actually further south in Calabria, Puglia and Molise where it is likely used for bulk wine production.

I was able to track down two wines featuring the Manzoni Bianco grape. The first was the 2009 Pratello "Lieti Conversari," which I picked up from my friends at the Spirited Gourmet for around $25. This wine is 100% Manzoni Bianco from the Brescia region of Lombardy. The grapes for this wine are hand harvested and 80% are fermented in stainless steel while 20% are fermented in oak barrels for 3-4 months (it is unclear whether it is new oak or not, but the wine didn't taste oaky to me at all and I would have guessed this saw 100% stainless steel). In the glass the wine was a medium lemon gold color. The nose was moderately intense with aromas of white peach, green apple, pear and grapefruit. On the palate the wine was on the lighter side of medium with fairly high acidity. There were flavors of grapefruit, lime, racy green apple, pear and white peach. It felt like there was still a slight prickle of CO2 to the wine as well, but since it didn't really dissipate, it was probably just an effect of the acidity. It was bright and zippy, despite the fact that it clocked in at a pretty hefty 14% alcohol. I found it lithe, vibrant and very enjoyable overall. Fans of snappy high acid whites will find a lot to like here, but be careful as it wears the 14% alcohol well and it can sneak up on you.

The second wine that I tried was the 2010 "Fontanasanta" from Elisabetta Foradori, which I picked up for around $28 from my friends at the Wine Bottega. This wine is 100% Manzoni Bianco from the hills above Trentino that is left in contact with its skins after crushing for about a week in large, egg shaped cement containers (there's a biodynamic reason for this that I don't really buy, so I'll just leave it at that). The wine is then aged for 12 months in acacia casks prior to bottling. In the glass the wine was a medium bronze gold color. The nose was moderately intense with aromas of pear, toasted almond, honey, red apple and lemon peel. On the palate the wine was medium bodied with medium acidity. There were flavors of ripe apple, pear, almond, honeysuckle flower, pineapple and a touch of apple cider. It's difficult to imagine two wines more different from one another than the two I tried for this tasting. The Foradori was deep, rich and honeyed with lovely cidery notes and bit of oxidative tang. What it lacked in vibrancy and freshness, it made up for in depth and complexity. It's difficult to say which wine is "better" since both were clearly made to be such different things. In the spring and summer months, I'd probably reach for the Pratello, but in the cooler fall and winter, I'd definitely go for the Foradori. Both are very good, very interesting wines that really show what Incrocio Manzoni is capable of in careful hands.

CITATIONS

1) Lacombe, T., Boursiquot, J.M., Laucou, V., Di Vecchi-Staraz, M., Peros, J.P., & This, P. 2012. Large scale parentage analysis in an extended set of grapevine cultivars (Vitis vinifera L.). Theoretical and Applied Genetics. In press.

Friday, January 18, 2013

Garganega/Grecanico Dorato - Veneto and Sicily, Italy

I wasn't sure whether I was going to write about the Garganega grape or not. It is the 11th most planted grape in Italy with nearly 30,000 acres devoted to it and is the star grape (making up at least 70% of the blend) in one of the most common white wines from Italy, Soave. It's a grape right on the fringe of being fringe and I went back and forth about it for a long time. I ultimately decided to write about it, though, because it turns out that Garganega is a really interesting grape with connections to a surprisingly large number of other Italian grapes. I was also able to find some interesting wines made from it outside of the Soave region of the Veneto so I thought, what the heck, let's take a look at Garganega.

Garganega is one of the oldest grapes known in Italy. Its first appearance in the literature dates to a 13th century work by Pietro de Crescenzi which says that it was cultivated around Bologna (in Emilia-Romagna) and Padova (in the Veneto) at that time. It seemingly hasn't moved very much from this general area in the 800 or so years since de Crescenzi wrote his book since nearly all of the plantings of Garganega and nearly all of the DOC regions where it is approved for use are clustered in the Veneto with just a few in Lombardy, Trentino-Alto Adige and Umbria as well. There's a little bit of twist to that story, though. Some ampelographers noticed that Garganega looked an awful lot like a grape called Grecanico Dorato grown in Sicily, but nobody could quite figure out how or why the same grape would show up in such geographically disparate regions and nowhere in between. Grecanico had been known and grown in Sicily for hundreds of years while Garganega had been known in northeastern Italy for longer than that so while the hypothesis of the two grapes' synonymy was intriguing, it remained just a theory for many years.

In 2003, an Italian research team conducted a study on vines from the Veneto to see if and how any of them were related to one another. They tested three clones of each of fourteen different Veronese grapes, one of which was Garganega. The team then took the DNA data they obtained from their Garganega samples and compared them to an exiting profile for Grecanico Dorato from another team's experiments and found that "these cultivars are highly related and most likely represent the same grapevine." In 2008, another Italian team decided to look at the DNA from Garganega and Sangiovese and compare it to a wide range of grapes from all over Italy in order to see if they could find any interesting relationships. They tested samples of both Garganega and Grecanico Dorato and found that the two vines were definitely identical. This result confirmed a study done a year earlier (citation 1) that showed that not only was Garganega the same as Grecanico Dorato, but it was also the same as a grape called Malvasia de Manresa from Spain (which raises a whole bunch of interesting questions that I'm afraid I can't answer). The vine is no longer cultivated in Spain, but there are still some vines in holding collections in Europe.

The most interesting findings in these last two papers had to do with the other grape varieties that had a close relationship with Garganega. The team from citation 1 found that Garganega and another grape called Uva Sogra were the parents of Susumaniello, a red grape grown primarily in Puglia today. They also found that Garganega has a likely parent-offspring relationship with Malvasia di Candia, Trebbiano Toscana and a few other grapes that I've never heard of before. These results were confirmed in the 2008 study mentioned above and augmented by the discovery that Garganega also appears to have a parent-offspring relationship with Marzemina Bianca, Catarratto, Albana, Greco del Pollino and Empibotte. The connection with so many different grapes throughout Italy makes Garganega one of the most important cultivars in the history of Italian wine grape evolution. Though it is a very interesting question, I don't believe than anyone has given a satisfactory answer as to how the grape moved throughout the country of Italy to end up in two places so far apart, leaving only relatives in its wake. It is thought that since Garganega is more closely related to the vines of the Veneto, it likely came from there originally before making its way south to Sicily, and that's as good an explanation as any, I suppose.

I was able to try a variety of wines made from Garganega/Grecanico from both the Veneto and from Sicily. The first was the 2008 "Pico" from Angiolino Maule, which I picked up from my friends at the Wine Bottega for around $30. This wine is 100% Garganega from Maule's vines in the Veneto. The grapes are crushed and left to ferment in open vats without any temperature control for 2-4 days. The wine is then moved to old (neutral) 1500 liter barrels for a year prior to bottling without any fining or filtration. In the glass the wine was a hazy medium gold color. The nose was fairly intense with aromas of ripe apple, white flowers, pineapple, honeysuckle, pear and grapefruit. It was deep and wonderful, revealing something new with every sniff. On the palate the wine was medium bodied with fairly high acidity and just a touch of tannic grip. There were flavors of ripe apple, honey, pineapple, apple cider, Meyer lemon, almonds and grapefruit. This blows every Soave I've ever had completely out of the water. It is a complex, fascinating wine that was an absolute delight to drink. If you've given up on the Garganega grape because you've only had a few bland examples from Soave, let this bottle change your mind.

The second wine that I tried was the 2010 Planeta "La Segreta" ($15 retail) from Sicily. This is a blended wine made from 50% Grecanico, 30% Chardonnay, 10% Viognier and 10% Fiano. In the glass the wine was a medium lemon gold color. The nose was moderately intense with aromas of pear, white peach, lemon peel, chalk and something faintly tropical. On the palate the wine was medium bodied with medium acidity. There were flavors of white grapefruit, cut grass, citrus peel, pear and ripe apple with a subtle stony minerality to the finish. Overall, I found the wine sharp and snappy with a bit of fleshiness to it that helped to balance it out. It was really citrusy and grassy and reminded me a lot of Sauvignon Blanc, which is one of the few grapes not in the blend at all. It almost tasted a little under-ripe, which is surprising when you consider how much warmer Sicily is than the Veneto. I thought it was a decent enough wine, but there wasn't too much in it to get me excited and it really just seemed flat and uninteresting after drinking the Pico.

The final wine that I tried was the Cornelissan Munjebel Bianco 6 from Sicily, which I picked up on clearance at the Spirited Gourmet for around $67. I've written about Frank Cornelissan before, but his story is worth telling again. In short, Frank Cornelissan is what happens when you extend the natural wine movement to its most extreme end. His 8.5 hectares of vines consist of many different native Sicilian vines, inter-planted among one another, that are never sprayed and which are all harvested at the same time. I don't know precisely what is in the Munjebel Bianco, but I've been told that the bulk of it is likely Grecanico with some Coda di Volpe, Carricante and Catarratto as well. After harvest, the grapes are crushed and fermented in 400 liter terracotta vessels buried in the ground. The skins and seeds are left in contact with the fermenting juice for up to a whopping 7-14 months for both red and white wines. The wines are then pressed and returned to terracotta vessels to be aged "until several full cosmic cycles have passed" before bottling. The vines are planted on a slope of Mt. Etna and his three different price points for his wines correspond to the altitude at which the grapes used for the wine are planted (the higher the altitude, the higher the price). Munjebel is the middle tier, and the six refers to the fact that this is the sixth Munjebel white that Frank has produced. The wines are not vintage dated, but savvy Cornelissan drinkers can tell which vintage a given wine is from the wine's name and its number. I'm not one of those drinkers, so I have no idea what year this wine is from (though Jamie Goode over at the Wine Anorak says that it's 2009, and I suppose he would know).

Cornelissan's wines are bottled with no sulfur dioxide and with no fining or filtration at any step along the way. When you look through the bottle at the liquid inside, I'll admit it doesn't look very appetizing as there are frequently both large chunks and fine cloudy particulates that float around inside the bottle at the slightest movement. The wines can be a bit of a gamble since the lack of preservatives means that if the wine was stored improperly, the chance of microbial spoilage goes up considerably. This is a sobering prospect for a bottle that costs $67 on clearance, and an even more sobering prospect for the $150 demanded for his highest-end bottling, the Magma. I was sure to store my bottle carefully and also carefully poured it into my glass, where it was a hazy bronze color that was almost a little tawny. The nose was moderately intense with aromas of cider, honey, caramel apple, toasted nuts and autumn spice. On the palate the wine was medium bodied with high acid. The first descriptor I have in my notes is "crazy." There was a slight tingle of CO2 followed by flavors of toasted nuts, unfiltered cider, golden apple, pear and pickle juice. I've tasted only a handful of wines from Cornelissan and only drunk two full bottles of his wines, but their hallmark to me is the excellent balance between oxidation and bright, zippy freshness. I have always found his wines fascinating and deeply interesting, but I understand that they are an acquired taste in a niche market. I wouldn't pair this wine with any food at all. It's the kind of thing that really needs to be experienced on its own. It really demands the drinker's full attention and should be drunk slowly, over the course of several hours, so one can really see the wine evolve and devolve. These aren't wines that I would want to drink every day, but when I do find myself with a Cornelissan wine open in front of me, it's always a memorable experience.

Garganega is one of the oldest grapes known in Italy. Its first appearance in the literature dates to a 13th century work by Pietro de Crescenzi which says that it was cultivated around Bologna (in Emilia-Romagna) and Padova (in the Veneto) at that time. It seemingly hasn't moved very much from this general area in the 800 or so years since de Crescenzi wrote his book since nearly all of the plantings of Garganega and nearly all of the DOC regions where it is approved for use are clustered in the Veneto with just a few in Lombardy, Trentino-Alto Adige and Umbria as well. There's a little bit of twist to that story, though. Some ampelographers noticed that Garganega looked an awful lot like a grape called Grecanico Dorato grown in Sicily, but nobody could quite figure out how or why the same grape would show up in such geographically disparate regions and nowhere in between. Grecanico had been known and grown in Sicily for hundreds of years while Garganega had been known in northeastern Italy for longer than that so while the hypothesis of the two grapes' synonymy was intriguing, it remained just a theory for many years.

In 2003, an Italian research team conducted a study on vines from the Veneto to see if and how any of them were related to one another. They tested three clones of each of fourteen different Veronese grapes, one of which was Garganega. The team then took the DNA data they obtained from their Garganega samples and compared them to an exiting profile for Grecanico Dorato from another team's experiments and found that "these cultivars are highly related and most likely represent the same grapevine." In 2008, another Italian team decided to look at the DNA from Garganega and Sangiovese and compare it to a wide range of grapes from all over Italy in order to see if they could find any interesting relationships. They tested samples of both Garganega and Grecanico Dorato and found that the two vines were definitely identical. This result confirmed a study done a year earlier (citation 1) that showed that not only was Garganega the same as Grecanico Dorato, but it was also the same as a grape called Malvasia de Manresa from Spain (which raises a whole bunch of interesting questions that I'm afraid I can't answer). The vine is no longer cultivated in Spain, but there are still some vines in holding collections in Europe.

The most interesting findings in these last two papers had to do with the other grape varieties that had a close relationship with Garganega. The team from citation 1 found that Garganega and another grape called Uva Sogra were the parents of Susumaniello, a red grape grown primarily in Puglia today. They also found that Garganega has a likely parent-offspring relationship with Malvasia di Candia, Trebbiano Toscana and a few other grapes that I've never heard of before. These results were confirmed in the 2008 study mentioned above and augmented by the discovery that Garganega also appears to have a parent-offspring relationship with Marzemina Bianca, Catarratto, Albana, Greco del Pollino and Empibotte. The connection with so many different grapes throughout Italy makes Garganega one of the most important cultivars in the history of Italian wine grape evolution. Though it is a very interesting question, I don't believe than anyone has given a satisfactory answer as to how the grape moved throughout the country of Italy to end up in two places so far apart, leaving only relatives in its wake. It is thought that since Garganega is more closely related to the vines of the Veneto, it likely came from there originally before making its way south to Sicily, and that's as good an explanation as any, I suppose.

I was able to try a variety of wines made from Garganega/Grecanico from both the Veneto and from Sicily. The first was the 2008 "Pico" from Angiolino Maule, which I picked up from my friends at the Wine Bottega for around $30. This wine is 100% Garganega from Maule's vines in the Veneto. The grapes are crushed and left to ferment in open vats without any temperature control for 2-4 days. The wine is then moved to old (neutral) 1500 liter barrels for a year prior to bottling without any fining or filtration. In the glass the wine was a hazy medium gold color. The nose was fairly intense with aromas of ripe apple, white flowers, pineapple, honeysuckle, pear and grapefruit. It was deep and wonderful, revealing something new with every sniff. On the palate the wine was medium bodied with fairly high acidity and just a touch of tannic grip. There were flavors of ripe apple, honey, pineapple, apple cider, Meyer lemon, almonds and grapefruit. This blows every Soave I've ever had completely out of the water. It is a complex, fascinating wine that was an absolute delight to drink. If you've given up on the Garganega grape because you've only had a few bland examples from Soave, let this bottle change your mind.

The second wine that I tried was the 2010 Planeta "La Segreta" ($15 retail) from Sicily. This is a blended wine made from 50% Grecanico, 30% Chardonnay, 10% Viognier and 10% Fiano. In the glass the wine was a medium lemon gold color. The nose was moderately intense with aromas of pear, white peach, lemon peel, chalk and something faintly tropical. On the palate the wine was medium bodied with medium acidity. There were flavors of white grapefruit, cut grass, citrus peel, pear and ripe apple with a subtle stony minerality to the finish. Overall, I found the wine sharp and snappy with a bit of fleshiness to it that helped to balance it out. It was really citrusy and grassy and reminded me a lot of Sauvignon Blanc, which is one of the few grapes not in the blend at all. It almost tasted a little under-ripe, which is surprising when you consider how much warmer Sicily is than the Veneto. I thought it was a decent enough wine, but there wasn't too much in it to get me excited and it really just seemed flat and uninteresting after drinking the Pico.

Cornelissan's wines are bottled with no sulfur dioxide and with no fining or filtration at any step along the way. When you look through the bottle at the liquid inside, I'll admit it doesn't look very appetizing as there are frequently both large chunks and fine cloudy particulates that float around inside the bottle at the slightest movement. The wines can be a bit of a gamble since the lack of preservatives means that if the wine was stored improperly, the chance of microbial spoilage goes up considerably. This is a sobering prospect for a bottle that costs $67 on clearance, and an even more sobering prospect for the $150 demanded for his highest-end bottling, the Magma. I was sure to store my bottle carefully and also carefully poured it into my glass, where it was a hazy bronze color that was almost a little tawny. The nose was moderately intense with aromas of cider, honey, caramel apple, toasted nuts and autumn spice. On the palate the wine was medium bodied with high acid. The first descriptor I have in my notes is "crazy." There was a slight tingle of CO2 followed by flavors of toasted nuts, unfiltered cider, golden apple, pear and pickle juice. I've tasted only a handful of wines from Cornelissan and only drunk two full bottles of his wines, but their hallmark to me is the excellent balance between oxidation and bright, zippy freshness. I have always found his wines fascinating and deeply interesting, but I understand that they are an acquired taste in a niche market. I wouldn't pair this wine with any food at all. It's the kind of thing that really needs to be experienced on its own. It really demands the drinker's full attention and should be drunk slowly, over the course of several hours, so one can really see the wine evolve and devolve. These aren't wines that I would want to drink every day, but when I do find myself with a Cornelissan wine open in front of me, it's always a memorable experience.

Wednesday, January 16, 2013

Seyval Blanc - Haverhill, Massachusetts, USA

Hello friends and neighbors and welcome to Fringe Wine's 250th post! We've covered hundreds of grapes over the course of the previous 249 posts, but there are still literally thousands of others out there. My ambition is not to try all of them, but merely to try as many as I can and write what I learn about them and what I think about the wines they produce. Today I'd like to take a look at a hybrid grape that's relatively common around where I live (the northeastern United States) and in a few other (cold climate) places, but which isn't very well known outside of these limited areas. The grape I'm talking about is called Seyval Blanc, or more cumbersomely Seyve-Villard 5276. It was created by the French father and son-in-law team of Victor Villard and Bertille Seyve who were themselves disciples of the great French hybridizer Albert Seibel, creator of thousands of grapes like Chancellor and Verdelet. Bertille Seyve was also the father of Joannes Seyve, who created the Chambourcin grape, and Bertille Seyve, Jr., who also tried his hand at breeding grapes, but was not as successful as his brother and father.

Seyval Blanc was created in Saint-Vallier, France (the name Seyval is a contraction of Seyve and Vallier), by crossing Seibel 5656 with Rayon d'Or. Both of these grapes are complex hybrids, which just means that they have more than two different grape species in their lineage. A simple hybrid would be the result of a crossing between two grapes that were of different species and which had no other species in its its parentage. A pure Vitis vinifera crossed with a pure Vitis labrusca would produce a simple hybrid. If we crossed this simple hybrid with a pure Vitis aesitvalis, the resulting offspring would have three different species of grapes in its lineage and it would be a complex hybrid. This pedigree chart (from the publisher of Wine Grapes) shows just how complex Seyval Blanc's lineage is (it is erroneously listed as Seibel 5276 on the chart and is on the third row from the bottom towards the left of page 2). While Seyval Blanc isn't quite as complex as Traminette, there are still many different grape species in its pedigree as well as several vinifera vines as well.

Seyval Blanc is also important as a parent variety and was used to breed Cayuga White, Chardonel, La Crosse and Melody, among others. It is prized by growers and breeders alike for its high yields, disease resistance and its cold hardiness as well as its lack of foxy aromas and flavors. It can generally be found in cool climate areas where other varieties, especially vinifera varieties, are unable to get fully ripe. It was at one time the most widely planted grape in the UK, but its plantings have fallen to less than 100 hectares as of 2009 (which is still 6.5% of the total vineyard area of the country, though). It is also popular in Canada and the mid-western and northeastern United States, where it was once the most widely planted grape in that region (and still may be, but I haven't seen any recent statistics).

A few months back, I was in northern Massachusetts and paid a visit to Willow Spring Vineyards in Haverhill. I met with Jim Parker, owner of the winery, and he gave me a tour of his vineyards and of the grand centerpiece of the whole endeavor, the 18th Century barn located on the property. When Jim and Cindy bought the property, the barn was in a state of dilapidation and disrepair, as was the land surrounding it. Very shortly after finalizing the purchase, the pair received a letter from the city building inspector informing them that the barn was a condemned building and must be either torn down immediately or repaired. Jim promised the barn's former owner that he would fix up the property, and so that's exactly what he set out to do. Jim's a handy guy and so he decided to do the renovation himself. He bought the property in 2001 and has been working on it for more than 10 years at this point, but the finished (or near finished) product is remarkable. When I arrived for my scheduled visit, Jim was out front with some of his friends and a backhoe putting the finishing touches on the front entrace. That entrance leads into the tasting room which still has much of the original lumber used to build the barn. It's a wide open area that also doubles as an event center. There's a large wraparound porch that Jim has added that looks out onto his vines. The winery itself is located underneath the main floor of the barn (see the white door beneath the deck in the picture below).

Jim knew when he bought the property that he wanted to grow something on the land, but wasn't sure exactly what. After visiting a micro brewery with some friends on a ski trip, Jim's friends suggested that he grow hops, but for some reason, Jim said he saw vines growing on the property. He had never tried to grow grapes before, but that didn't stop him from jumping in with both feet. Jim read widely and voraciously on viticulture and enology, met other local winemakers and went to conferences to learn as much as he could. He started out planting Vignoles, Seyval Blanc, Marechal Foch and Leon Millot and has since added a few vines of Chardonnay as well. The vineyards are on a south facing slope so they get maximum exposure to the sun and the cold air flows down the hill to protect the vines from frost, which is very important this far north. Jim and his friends tend to the vines themselves and Jim's daughter Brandi has recently joined the team as head winemaker after an apprenticeship at another local winery. When I visited, Willow Spring was available to visit by appointment only, though they plan to open to the public soon. Those interested in visiting can email Jim directly at jim.willowspring@yahoo.com, and I highly recommend that you do as the barn is beautiful and Jim is an engaging and gracious host whose enthusiasm for his project is infectious.

When I was there, I picked up a bottle of his Leon Millot, which I'll be writing about a bit later, as well as the last bottle of his 2011 Seyval Blanc (his wines are not labeled with a vintage, though they are vintage wines, and he told me this was the 2011). This bottle cost about $14 in the tasting room. In the glass the wine was a very pale silvery lemon color. The nose was somewhat reserved with aromas of green melon, pear, golden apple and banana. On the palate the wine was light bodied with high acidity. It was maybe just a touch off-dry with flavors of lime, green apple, tart pineapple and green melon. It clocks in at only 11.5% abv and is lean, racy and sharp. I love high acid white wines and this particular bottle was right up my alley. It's difficult to believe that these guys have only been making wine for a few vintages as this was a very polished effort that definitely shows a lot of promise. Willow Spring is a winery to keep an eye on and is a place I will certainly be visiting again before too long.

Those interested in learning more about Willow Spring should check out this video feature on YouTube and this article.

Seyval Blanc was created in Saint-Vallier, France (the name Seyval is a contraction of Seyve and Vallier), by crossing Seibel 5656 with Rayon d'Or. Both of these grapes are complex hybrids, which just means that they have more than two different grape species in their lineage. A simple hybrid would be the result of a crossing between two grapes that were of different species and which had no other species in its its parentage. A pure Vitis vinifera crossed with a pure Vitis labrusca would produce a simple hybrid. If we crossed this simple hybrid with a pure Vitis aesitvalis, the resulting offspring would have three different species of grapes in its lineage and it would be a complex hybrid. This pedigree chart (from the publisher of Wine Grapes) shows just how complex Seyval Blanc's lineage is (it is erroneously listed as Seibel 5276 on the chart and is on the third row from the bottom towards the left of page 2). While Seyval Blanc isn't quite as complex as Traminette, there are still many different grape species in its pedigree as well as several vinifera vines as well.

Seyval Blanc is also important as a parent variety and was used to breed Cayuga White, Chardonel, La Crosse and Melody, among others. It is prized by growers and breeders alike for its high yields, disease resistance and its cold hardiness as well as its lack of foxy aromas and flavors. It can generally be found in cool climate areas where other varieties, especially vinifera varieties, are unable to get fully ripe. It was at one time the most widely planted grape in the UK, but its plantings have fallen to less than 100 hectares as of 2009 (which is still 6.5% of the total vineyard area of the country, though). It is also popular in Canada and the mid-western and northeastern United States, where it was once the most widely planted grape in that region (and still may be, but I haven't seen any recent statistics).

|

| Inside the barn/tasting room |

|

| Exterior of barn. The wraparound deck is now covered. |

When I was there, I picked up a bottle of his Leon Millot, which I'll be writing about a bit later, as well as the last bottle of his 2011 Seyval Blanc (his wines are not labeled with a vintage, though they are vintage wines, and he told me this was the 2011). This bottle cost about $14 in the tasting room. In the glass the wine was a very pale silvery lemon color. The nose was somewhat reserved with aromas of green melon, pear, golden apple and banana. On the palate the wine was light bodied with high acidity. It was maybe just a touch off-dry with flavors of lime, green apple, tart pineapple and green melon. It clocks in at only 11.5% abv and is lean, racy and sharp. I love high acid white wines and this particular bottle was right up my alley. It's difficult to believe that these guys have only been making wine for a few vintages as this was a very polished effort that definitely shows a lot of promise. Willow Spring is a winery to keep an eye on and is a place I will certainly be visiting again before too long.

Those interested in learning more about Willow Spring should check out this video feature on YouTube and this article.

Monday, January 14, 2013

Malvar - Vinos de Madrid, Spain

|

| Image from the excellent Vinos Ambiz blog |

I checked out some of the citations given for the differentiation between Lairén and Airén and also some of the other papers concerning Spanish wines that I have on hand and noticed something interesting. Not only do none of these papers indicate that Malvar and Lairén are synonyms, but several of them (citation 1 and 2 below) have huge charts showing the genetic profiles of all the grapes that were analyzed in each particular study. These charts had entries for Airén, Lairén and Malvar and all three profiles were different. For those new to these studies (some background here), if all three grapes have distinct DNA profiles (as these three do), then they're all separate grape varieties. Furthermore, one of these studies (citation 1) was specifically cited by Vouillamoz in Wine Grapes as providing evidence that Lairén and Airén were two different grapes (the other study he cites also shows that those two grapes are different, but it doesn't mention Malvar at all, so it doesn't concern us here).

Despite the claim put forward in the OCW and in Wine Grapes, I cannot find any evidence that indicates that Malvar and Lairén are the same grape. A few sources indicate that Malvar and Airén have historically been confused with one another, and one paper even has a sample labeled Malvar that was actually Airén, but they clarify this finding by saying "'Malvar' is sometimes confused with 'Airén' (IBAÑEZ et al. 2003), but is clearly separable by microsatellite analysis; hence, accession 3 is considered to be a misnamed genotype and not a homonym of 'Malvar' (43)." As you might expect, Lairén and Airén have historically been confused for one another as well, but as we've already indicated, several DNA analyses have shown that these are two different grapes. No study that I've been able to find has given any indication that Malvar is the same grape as Lairén, and in fact, all the genetic evidence that I've seen seems to clearly indicate that they are separate grapes.

Now that we know what Malvar probably isn't, let's try to find out a little bit more about what it is. Malvar is a white wine grape that is grown to a very limited extent in central Spain, and in 2008 its planting figures stood at around 650 acres. It is most often found in the Vinos de Madrid DO, which is located just south of the city of Madrid and just north of the region of La Mancha. It is also permitted in Mondéjar and Ribera del Guadiana, but it is really most important in Madrid. Compared to Airén, Malvar is a less generous yielder and more of an early ripener. It also has higher acidity and some producers produce a late harvest wine from its berries because of its ability to maintain balance late into its ripening process. When made into a table wine, Malvar is often blended with Airén, but several producers do make varietal versions as well.