Hello everyone and welcome to what will almost certainly my final post of 2012. This is my 117th post of the year, just barely surpassing last year's total of 112 posts, and I hope that people have found them interesting and informative. I'd like to send 2012 off by taking a look at the Clairette grape, which I thought would be relatively easy to find a bottle of, but which turned out to be more difficult to track down than I had thought. There were about 6,000 acres of Clairette planted in France as of 2009, but this number has been declining dramatically over the past half century. Plantings stood at almost 35,000 acres in 1958, but they were down to around 7,500 acres by the 1990's. It is also grown to a limited extent in Italy (where, oddly enough, it is permitted in the blend for Nuragus di Cagliari), Australia and South Africa with a few hundred acres under vine in each of those countries..

The reason for Clairette's recent decline can mostly be chalked up to changing fashions. Clairette is a very low-acid grape that has a tendency to oxidize very easily. There was a time when white wines were expected to be a little (or a lot) oxidized, and when those characteristics were prized by consumers and connoisseurs, Clairette was a much more popular grape. Furthermore, these characteristics also made Clairette popular for the production of Vermouth, but as the popularity of that particular drink has declined, so has the popularity of Clairette. In today's world, Clairette is typically used as a blending grape and it is often paired with higher acid grapes like Picpoul de Pinet or with Grenache Blanc, Roussanne and/or Marsanne. Clairette usually contributes aromatic elements and softness to the final blend when it is used. There are a handful of appellations where Clairette is required to be the dominant or the sole grape in the blend and nearly all of them have the word "Clairette" right in them for convenience. Clairette de Die, Clairette de Bellegarde and Clairette de Languedoc are probably the most common, but there's also Coteaux de Die and, somewhat surprisingly, Crémant de Die, which is a sparkling wine made predominantly from Clairette grapes.

References to a grape called Clairette can be traced back to the 16th Century, but it isn't clear whether this is the same grape that we know as Clairette today. Clairette means something like "light white," and could conceivably have referred to many different grape varies through the years. There's a bit of confusion even today, as Ugni Blanc is sometimes known as Clairette Ronde in some parts of the Languedoc (though the two grapes are not related to one another). The Erbaluce grape in Italy has a similar etymology, and this study done in 2001 found that the two grapes shared 50% of their alleles at the microsatellite loci investigated, but further testing has not been done to see whether the two grapes are really related to one another genetically or merely linguistically. There is also some evidence that suggests that Clairette may be related to Airén and/or Roditis, but further study needs to be done to determine just what the relationship might be.

I searched for well over year for a varietal Clairette wine, but was unable to find one. I eventually picked up a bottle of the 2011 Jean-Luc Colombo "Les Abeilles," which is 80% Clairette and 20% Roussane, from my friends over at Brookline Liquor Mart for around $14. In the glass the wine was a pale silvery lemon color. The nose was intense with aromas of peach, grapefruit, melon, white flowers and lime. On the palate the wine was medium bodied with fairly low acidity. There were flavors of grapefruit and pear along with a touch of grassy herbaceousness and a stony mineral finish. The flavor profile was broad and fat with a little bit of bitter citrus pith on the finish as well. The nose was really lovely, but the lack of acid kind of sunk this for me. The grassy flavor reminded me of Sauvignon Blanc, but it lacked the energy and vitality that really nice Sauvignon Blanc based wines have. If you're not really into high-acid white wines, then this is probably right up your alley, but if you're an acid freak like me, then you won't find very much to like here.

A blog devoted to exploring wines made from unusual grape varieties and/or grown in unfamiliar regions all over the world. All wines are purchased by me from shops in the Boston metro area or directly from wineries that I have visited. If a reviewed bottle is a free sample, that fact is acknowledged prior to the bottle's review. I do not receive any compensation from any of the wineries, wine shops or companies that I mention on the blog.

Friday, December 21, 2012

Monday, December 17, 2012

Roter Veltliner - Niederösterreich, Austria

I suppose when you decide to write about a grape called Roter Veltliner, it's probably best to go ahead and address the elephant in the room before going any further: no, Roter Veltliner is not related to Grüner Veltliner (or at least not very closely). This seems difficult to believe given the similarities of their names, but in 1998, an Austrian research team was able to show that not only were Grüner Veltliner and Roter Veltliner not related to one another, but further that Roter Veltliner actually seems to be the more important of the two cultivars in terms of genetic history and parentage (citation 1 below). Today I'd like to take a closer look at the Roter Veltliner grape and its little family circle.

Grüner Veltliner is certainly more widely available, widely grown and widely hailed than Roter Veltliner, but it has very limited family connections with other Austrian grape varieties. Grüner is the offspring of Savagnin/Traminer and an obscure grape called St. Georgen-Rebe, which was discovered in an overgrown patch in an abandoned lot in Austria (source). If there are any other grapes that Grüner has a first-degree relationship with, I have not come across them in any of the literature. Roter Veltliner, on the other hand, is a key part of what is commonly known as the "Veltliner family," which Grüner is actually not a member of. The family relationships break down like this:

- Roter Veltliner crossed with Savagnin to create Rotgipfler (which makes Rotgipfler and Grüner Veltliner half-siblings since they share Savagnin as a parent)

- Roter Veltliner also crossed with Silvaner (which is itself an offspring of Savagnin and Österreichisch weiß) to create Neuburger and Frühroter Veltliner

- Frühroter Veltliner was crossed with Grauer Portugieser (which is the pink-berried form of Blauer Portugieser) to create Jubiläumsrebe

Wine Grapes reports that Roter Veltliner likely crossed with a close relative of Traminer/Savagnin to create Zierfandler, but the paper that they cite for support for this doesn't seem to mention Zierfandler at all (though it is in German, and I could be missing it [link immediately begins to download PDF]). Furthermore, in the 1998 paper referenced above, the authors specifically say "in contrast to previous assumptions...no close genetic relationship between Rotgipfler and Zierfandler could be detected." If the two grapes shared a common parent, you would expect them to have between 50 and 100% similar DNA, but this study indicates that they could find no such similarity between the two. The lead author on the Wine Grapes referenced paper is actually also an author on the 1998 paper mentioned above (as well as the lead author on a follow-up paper in 2000, citation 2 below, which also doesn't mention Zierfandler but which traces the Veltliner family tree pretty thoroughly), so it seems odd that he'd not include those findings in either of the papers I've cited but would in the German paper cited by WG. Since I can't find any published results which show a first degree relationship between Zierfandler and Roter Veltliner or Rotgipfler, and since the papers I've read certainly would have performed the analysis to check for a relationship, I feel OK in saying that there probably isn't one.

Some of you may still be puzzling over the fact that there is no relationship between Roter Veltliner and Grüner Veltliner despite their similar sounding names. Since Grüner means "green"(and Grüner's berries are green) and Roter means "red" (and Roter's berries are red) we should be able to find some link between the two grapes through the word "Veltliner," right? Unfortunately, it isn't totally clear just where the "Veltliner" part of the name comes from. Many believe that it comes from the word "Veltlin," which is the German word for "Valtellina," which is a valley in northern Lombardia in Italy that borders Switzerland. The story goes that Grüner Veltliner was named for this valley because it was introduced from there by the Romans. The problem with this is that the name only seems to appear in print after 1855 and prior to that, the grape was called Weißgipfler or Grüner Muskateller (despite the fact that it is not related to the Muscat family either). If the Veltliner were a reference to a Roman origin, it should be traceable further back than that through the historical record, but it doesn't seem to be. This piece gives some interesting history, but it seems that the answer to the origin of the Veltliner name is still a mystery (though it is worth nothing that all of this research was done for Grüner and not Roter Veltliner, which is apparently not popular enough to warrant this kind of scholarship on its own).

Grüner Veltliner is easily the most widely planted grape in Austria, covering just over 42,000 acres of land in Austria. Roter Veltliner, by contrast, is only planted on about 640 acres in Austria and is in fact more widely planted in Slovakia, where it covers nearly 900 acres of land. As you might expect, wines made from it are considerably harder to find than wines made from Grüner, but I was able to find a bottle of the 2009 Ecker Eckhof Roter Veltliner from my friends at the Spirited Gourmet for around $20. In the glass the wine was a medium silvery lemon color. The nose was fairly intense with lemon and lime citrus aromas along with some green apple and a touch of apricot. On the palate the wine was medium bodied with fairly high acidity. There were flavors of lemon, green apple, lime peel, and lees with a mouthwatering, stony mineral finish. It was bright, zippy and tart but with nice body and complexity as well. I thoroughly enjoyed it and found myself disappointed that there weren't more examples around that I could try. It's definitely something I'll be keeping an eye out for in the future.

1) Sefc, KM, Steinkellner, H, Glossl, J, Kampfer, S, & Regner, F. 1998. Reconstruction of a grapevine pedigree by microsatellite analysis. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 97, pp 227-231

2) Regner, F, Sefc, K, Glossl, J & Steinkellner, H. 2000. Parentage analysis and pedigree reconstruction of vine cultivars using microsatellite markers. Acta Horticulturae. 528, pp 133-138,

Grüner Veltliner is certainly more widely available, widely grown and widely hailed than Roter Veltliner, but it has very limited family connections with other Austrian grape varieties. Grüner is the offspring of Savagnin/Traminer and an obscure grape called St. Georgen-Rebe, which was discovered in an overgrown patch in an abandoned lot in Austria (source). If there are any other grapes that Grüner has a first-degree relationship with, I have not come across them in any of the literature. Roter Veltliner, on the other hand, is a key part of what is commonly known as the "Veltliner family," which Grüner is actually not a member of. The family relationships break down like this:

- Roter Veltliner crossed with Savagnin to create Rotgipfler (which makes Rotgipfler and Grüner Veltliner half-siblings since they share Savagnin as a parent)

- Roter Veltliner also crossed with Silvaner (which is itself an offspring of Savagnin and Österreichisch weiß) to create Neuburger and Frühroter Veltliner

- Frühroter Veltliner was crossed with Grauer Portugieser (which is the pink-berried form of Blauer Portugieser) to create Jubiläumsrebe

Wine Grapes reports that Roter Veltliner likely crossed with a close relative of Traminer/Savagnin to create Zierfandler, but the paper that they cite for support for this doesn't seem to mention Zierfandler at all (though it is in German, and I could be missing it [link immediately begins to download PDF]). Furthermore, in the 1998 paper referenced above, the authors specifically say "in contrast to previous assumptions...no close genetic relationship between Rotgipfler and Zierfandler could be detected." If the two grapes shared a common parent, you would expect them to have between 50 and 100% similar DNA, but this study indicates that they could find no such similarity between the two. The lead author on the Wine Grapes referenced paper is actually also an author on the 1998 paper mentioned above (as well as the lead author on a follow-up paper in 2000, citation 2 below, which also doesn't mention Zierfandler but which traces the Veltliner family tree pretty thoroughly), so it seems odd that he'd not include those findings in either of the papers I've cited but would in the German paper cited by WG. Since I can't find any published results which show a first degree relationship between Zierfandler and Roter Veltliner or Rotgipfler, and since the papers I've read certainly would have performed the analysis to check for a relationship, I feel OK in saying that there probably isn't one.

Some of you may still be puzzling over the fact that there is no relationship between Roter Veltliner and Grüner Veltliner despite their similar sounding names. Since Grüner means "green"(and Grüner's berries are green) and Roter means "red" (and Roter's berries are red) we should be able to find some link between the two grapes through the word "Veltliner," right? Unfortunately, it isn't totally clear just where the "Veltliner" part of the name comes from. Many believe that it comes from the word "Veltlin," which is the German word for "Valtellina," which is a valley in northern Lombardia in Italy that borders Switzerland. The story goes that Grüner Veltliner was named for this valley because it was introduced from there by the Romans. The problem with this is that the name only seems to appear in print after 1855 and prior to that, the grape was called Weißgipfler or Grüner Muskateller (despite the fact that it is not related to the Muscat family either). If the Veltliner were a reference to a Roman origin, it should be traceable further back than that through the historical record, but it doesn't seem to be. This piece gives some interesting history, but it seems that the answer to the origin of the Veltliner name is still a mystery (though it is worth nothing that all of this research was done for Grüner and not Roter Veltliner, which is apparently not popular enough to warrant this kind of scholarship on its own).

Grüner Veltliner is easily the most widely planted grape in Austria, covering just over 42,000 acres of land in Austria. Roter Veltliner, by contrast, is only planted on about 640 acres in Austria and is in fact more widely planted in Slovakia, where it covers nearly 900 acres of land. As you might expect, wines made from it are considerably harder to find than wines made from Grüner, but I was able to find a bottle of the 2009 Ecker Eckhof Roter Veltliner from my friends at the Spirited Gourmet for around $20. In the glass the wine was a medium silvery lemon color. The nose was fairly intense with lemon and lime citrus aromas along with some green apple and a touch of apricot. On the palate the wine was medium bodied with fairly high acidity. There were flavors of lemon, green apple, lime peel, and lees with a mouthwatering, stony mineral finish. It was bright, zippy and tart but with nice body and complexity as well. I thoroughly enjoyed it and found myself disappointed that there weren't more examples around that I could try. It's definitely something I'll be keeping an eye out for in the future.

1) Sefc, KM, Steinkellner, H, Glossl, J, Kampfer, S, & Regner, F. 1998. Reconstruction of a grapevine pedigree by microsatellite analysis. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 97, pp 227-231

2) Regner, F, Sefc, K, Glossl, J & Steinkellner, H. 2000. Parentage analysis and pedigree reconstruction of vine cultivars using microsatellite markers. Acta Horticulturae. 528, pp 133-138,

Friday, December 14, 2012

Altesse/Roussette - Jongieux, Savoie & Montagnieu, Bugey, France

It's kind of hard to believe that it's been almost two years since I wrote about the Jacquère grape from Savoie and the Mondeuse grape from Bugey in the eastern Alpine regions of France, but it's true. It is also true that I haven't written any other posts on wines from those two regions since those first two (though I did write the section on Savoie for the AG Wine iPhone/iPad app). The reason is pretty simple: these are small regions in France that not only don't make very much wine, but also don't export very much either. They're big skiing areas that attract a lot of tourists, and much of the local production is consumed within the region by the tourists and the locals. Jacquère is getting a bit more common on US shelves, but it's not becoming a mainstream wine by any stretch of the imagination. It's much more difficult to find wines made from some of the other grapes from these regions, but I was recently able to try three different wines featuring Altesse, which is also known as Roussette, so I'd like to talk a little bit about that grape today.

Though it is found almost exclusively in Savoie and Bugey in eastern France, Altesse has long been suspected of being an import from somewhere further east. Its first mention in print is in 1774, and the story given at that time was that the vine was brought to the region from Cyprus by one of the local princes. The name Altesse means "highness," and it was long thought that this name came from the fact that some royal or noble person brought the vine to the area from somewhere else. I would have assumed that "highness" was a reference to the altitude of the Alpine vineyards in the area and not to the stature of its alleged importer, but that explanation seems to have been a bit too pedestrian for some early historians. Wine Grapes gives at least four different explanations that have been scattered through the literature which purportedly give an account of how and when Altesse came to the vineyards of Savoie with dates varying between the 14th and 16th Centuries. Some say the grape came from Cyprus, while others say it came from Turkey. In the latter part of the 20th Century, the great French ampelographer Pierre Galet suggested that the vine actually came from Hungary, and, further, may actually be the same as Furmint, since he believed it did not appear to bear any relationship to any other French cultivars.

It looks like Galet, and most of the early historians, were probably wrong about Altesse, though. While I can't find any specific paper directly comparing the two grapes, the VIVC database does have DNA profiles for both Altesse and Furmint, and it's pretty clear that they're not only different grapes, but also probably not even that closely related. Wine Grapes says that Altesse is actually more closely related to Chasselas, and if you speak (or read) French, you can read a little bit about that here. Chasselas is thought to be native to the area around Lake Geneva, which sits right on the border between France and Switzerland and which is just northeast of Savoie. If Altesse is closely related to Chasselas, and Chasselas is essentially native to the region, then it stands to reason that Altesse is also likely native to the region, and is not an import from some exotic eastern land.

Altesse is also known as Roussette in many places because the grapes begin to take on a reddish hue as they ripen and the French word for reddish hue (or russet-colored) is rousse. It is particularly susceptible to a variety of fungal infections (both downy and powdery mildews as well as botrytis). Altesse is found most often in the Roussette de Savoie and the Roussette de Bugey AOCs, which are in Savoie and Bugey respectively, as you may have guessed. There are a few village names that can be appended to either AOC, and it used to be the case that wines labeled with a village name needed to be made from 100% Altesse, while wines simply carrying the Roussette de Savoie/Bugey label could have up to 50% Chardonnay added in. This practice is no longer allowed, and all wines labeled either Roussette de Bugey or Savoie must now be 100% Altesse. As of 2008, there were almost 900 acres of Altesse in France and just a little bit in Switzerland (compared to the nearly 2500 acres of Jacquère in France).

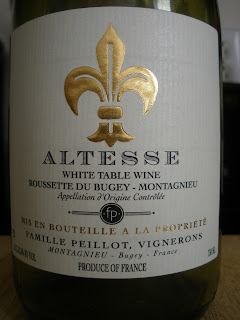

I was able to try three different wines featuring the Altesse grape. The first was the 2009 Famille Peillot Altesse from Bugey, which I picked up from my friends at the Wine Bottega for about $18. The wine is from the village of Montagnieu, which is one of the villages allowed to append its name to its wines. In the glass the wine was a pale silvery lemon color. The nose was reserved with a little bit of pear and chalk, but not much else. On the palate the wine was on the lighter side of medium with fairly high acidity. There were flavors of lime peel and light lime citrus along with some white pear, green apple, a touch of pineapple and chalk. It had the hallmark clean, fresh flavors, zippy acidity and solid minerality that I associate with Alpine wines and it had them in spades. It was lithe and nervy and was a real pleasure to drink. It represents an excellent value at only $18 and was still drinking very well after sitting in my cellar for over a year (I do sometimes lose things down there). I found myself wondering how much different an Altesse wine might be closer to the vintage year, so when I came across a 2011 wine, I snapped it up.

I picked up the 2011 Domaine Eugene Carrel Roussette de Savoie from my friends at the Spirited Gourmet for about $17. This wine is from the village of Jongieux, which is a village that can add its name to Vin de Savoie wines, but not to Roussette de Savoie wines (there is a separate cru designation called Marestel that can be added to the label for Roussette de Savoie, but this wine doesn't appear to be from that particular area of the village). In the glass the wine was a medium lemon gold color. The nose was fairly intense with fresh cut lemon, white pear, green apple, lime peel and chalk. On the palate the wine was medium bodied with medium acidity. There were flavors of banana, pear, lemon, green apple and a touch of lees with a strong, stony mineral finish. The banana is much more present as the wine warms up, though it does eventually blow off a little bit. The nose was much more intense on this wine than on the previous one, but I thought it was a bit flabbier on the palate and wasn't quite as focused. It's still a very nice wine for the money, but if I was forced to choose between the two, I'd reach for the wine from Bugey most of the time.

The final wine that I tried was a little bit different. It was the 2010 Côtillon des Dames from Jean-Yves Péron in Bugey, and it was an orange wine made from a combination of Altesse and Jacquère grapes. I picked this wine up from my friends at the Wine Bottega for about $25. In the glass the wine was a medium orange/amber-bronze color and was a little cloudy. The nose was fairly intense with honey, peach, honeysuckle flower, orange and pink grapefruit aromas. On the palate the wine was medium bodied with high acidity and a light tannic grip and maybe just a slight tickle of CO2. There were flavors of peach, grapefruit, honeysuckle and Meyer lemon along with a slight oxidative cidery tang. The flavors were rich and intense, but also nicely fresh and citrusy. The nose was just gorgeous and it was a little difficult to move past it and actually drink the wine. Once I did, though, I found it lithe and electric as the citrus fruits really danced around the bright nervy acid core. This was definitely my favorite of the three Altesse wines I tried, though it's not exactly a traditional bottling. If you come across it, though, give it a shot as it's a really fantastic bottle.

Though it is found almost exclusively in Savoie and Bugey in eastern France, Altesse has long been suspected of being an import from somewhere further east. Its first mention in print is in 1774, and the story given at that time was that the vine was brought to the region from Cyprus by one of the local princes. The name Altesse means "highness," and it was long thought that this name came from the fact that some royal or noble person brought the vine to the area from somewhere else. I would have assumed that "highness" was a reference to the altitude of the Alpine vineyards in the area and not to the stature of its alleged importer, but that explanation seems to have been a bit too pedestrian for some early historians. Wine Grapes gives at least four different explanations that have been scattered through the literature which purportedly give an account of how and when Altesse came to the vineyards of Savoie with dates varying between the 14th and 16th Centuries. Some say the grape came from Cyprus, while others say it came from Turkey. In the latter part of the 20th Century, the great French ampelographer Pierre Galet suggested that the vine actually came from Hungary, and, further, may actually be the same as Furmint, since he believed it did not appear to bear any relationship to any other French cultivars.

It looks like Galet, and most of the early historians, were probably wrong about Altesse, though. While I can't find any specific paper directly comparing the two grapes, the VIVC database does have DNA profiles for both Altesse and Furmint, and it's pretty clear that they're not only different grapes, but also probably not even that closely related. Wine Grapes says that Altesse is actually more closely related to Chasselas, and if you speak (or read) French, you can read a little bit about that here. Chasselas is thought to be native to the area around Lake Geneva, which sits right on the border between France and Switzerland and which is just northeast of Savoie. If Altesse is closely related to Chasselas, and Chasselas is essentially native to the region, then it stands to reason that Altesse is also likely native to the region, and is not an import from some exotic eastern land.

Altesse is also known as Roussette in many places because the grapes begin to take on a reddish hue as they ripen and the French word for reddish hue (or russet-colored) is rousse. It is particularly susceptible to a variety of fungal infections (both downy and powdery mildews as well as botrytis). Altesse is found most often in the Roussette de Savoie and the Roussette de Bugey AOCs, which are in Savoie and Bugey respectively, as you may have guessed. There are a few village names that can be appended to either AOC, and it used to be the case that wines labeled with a village name needed to be made from 100% Altesse, while wines simply carrying the Roussette de Savoie/Bugey label could have up to 50% Chardonnay added in. This practice is no longer allowed, and all wines labeled either Roussette de Bugey or Savoie must now be 100% Altesse. As of 2008, there were almost 900 acres of Altesse in France and just a little bit in Switzerland (compared to the nearly 2500 acres of Jacquère in France).

I was able to try three different wines featuring the Altesse grape. The first was the 2009 Famille Peillot Altesse from Bugey, which I picked up from my friends at the Wine Bottega for about $18. The wine is from the village of Montagnieu, which is one of the villages allowed to append its name to its wines. In the glass the wine was a pale silvery lemon color. The nose was reserved with a little bit of pear and chalk, but not much else. On the palate the wine was on the lighter side of medium with fairly high acidity. There were flavors of lime peel and light lime citrus along with some white pear, green apple, a touch of pineapple and chalk. It had the hallmark clean, fresh flavors, zippy acidity and solid minerality that I associate with Alpine wines and it had them in spades. It was lithe and nervy and was a real pleasure to drink. It represents an excellent value at only $18 and was still drinking very well after sitting in my cellar for over a year (I do sometimes lose things down there). I found myself wondering how much different an Altesse wine might be closer to the vintage year, so when I came across a 2011 wine, I snapped it up.

I picked up the 2011 Domaine Eugene Carrel Roussette de Savoie from my friends at the Spirited Gourmet for about $17. This wine is from the village of Jongieux, which is a village that can add its name to Vin de Savoie wines, but not to Roussette de Savoie wines (there is a separate cru designation called Marestel that can be added to the label for Roussette de Savoie, but this wine doesn't appear to be from that particular area of the village). In the glass the wine was a medium lemon gold color. The nose was fairly intense with fresh cut lemon, white pear, green apple, lime peel and chalk. On the palate the wine was medium bodied with medium acidity. There were flavors of banana, pear, lemon, green apple and a touch of lees with a strong, stony mineral finish. The banana is much more present as the wine warms up, though it does eventually blow off a little bit. The nose was much more intense on this wine than on the previous one, but I thought it was a bit flabbier on the palate and wasn't quite as focused. It's still a very nice wine for the money, but if I was forced to choose between the two, I'd reach for the wine from Bugey most of the time.

The final wine that I tried was a little bit different. It was the 2010 Côtillon des Dames from Jean-Yves Péron in Bugey, and it was an orange wine made from a combination of Altesse and Jacquère grapes. I picked this wine up from my friends at the Wine Bottega for about $25. In the glass the wine was a medium orange/amber-bronze color and was a little cloudy. The nose was fairly intense with honey, peach, honeysuckle flower, orange and pink grapefruit aromas. On the palate the wine was medium bodied with high acidity and a light tannic grip and maybe just a slight tickle of CO2. There were flavors of peach, grapefruit, honeysuckle and Meyer lemon along with a slight oxidative cidery tang. The flavors were rich and intense, but also nicely fresh and citrusy. The nose was just gorgeous and it was a little difficult to move past it and actually drink the wine. Once I did, though, I found it lithe and electric as the citrus fruits really danced around the bright nervy acid core. This was definitely my favorite of the three Altesse wines I tried, though it's not exactly a traditional bottling. If you come across it, though, give it a shot as it's a really fantastic bottle.

Labels:

Altesse,

Bugey,

France,

Jacquère,

Jongieux,

Montagnieu,

Roussette,

Savoie,

White Wine

Wednesday, December 12, 2012

Çimixà (Scimiscià) - Colline del Genovesato, Liguria, Italy

Though most of the wines I write about on this site are things that I've come across on my own, I do occasionally receive tips from readers about interesting grapes and wines they've come across that I might also be interested in. One of my more prolific tipsters is Tony from Pennsylvania who, in addition to providing a tasting note for my post on Nuragus, also has a sharp eye for unusual wines. He has previously pointed me to Albarín Blanco and Tempranillo Blanco, but the grape he directed me to for today's post is definitely more obscure than either of those.

A few months ago, Tony asked if I had ever heard of a grape called Çimixà from Liguria. Çimixà was definitely a new one on me, and a cursory glance on the internet revealed virtually no information the grape. I saw that Bisson, whose wines I had featured in some prior posts, and whose portfolio seems to be pretty well represented in the Boston area, made a varietal Çimixà, so I set about trying to track a bottle down. I asked around locally to see if anybody could get their hands on some, and came up empty. Not only that, but none of the guys I asked about ordering the wine had ever even heard of it, and these guys are pretty tough to stump. I was now getting more and more anxious to get my hands on a bottle. Tony pointed me in the direction of MCF Rare Wine in New York City, who had about half a dozen bottles in stock and who was willing to sell a bottle to me (all legally, of course).

Though I pulled the cork on my bottle a month or so ago, I've been quietly dreading having to write this post because, as I mentioned above, I wasn't able to find any information at all about Çimixà when I had previously searched online, and a new Google search didn't really get me very much new information either. I went to look the grape up in Wine Grapes, and began to get despondent when I didn't see an entry under Çimixà, so I checked the index and found that it was listed under the name Scimiscià. I know I was a little harsh on Wine Grapes in my review of that book, and I still stand by my criticisms, but it is really an excellent reference work and is very helpful for situations just like this one. Their entry on the grape indicates that it is one of those grapes (like Pugnitello or Nascetta or Pecorino, etc) that was on the brink of extinction, but was rescued by a gentleman named Marco Baciagalupo, a pastry chef from Genoa, Liguria. In the 1970's, Marco gathered together about 500 vines that were purported to be Çimixà and planted them all together in a single plot. A local cooperative took over the job of caring for these vines in the 1990's, and by 2003, the grape was included in the national register of varieties in Italy.

Eagle-eyed readers may note that the picture I've included with this post is for a grape called Genovese, and not Çimixà or Scimiscià. The reason for that is that a study done in 2009 found that the Scimiscià of Liguria was not only the same as the grape known as Frate Pelato in the Cinque Terre, but was also the same as the Genovese of Corsica. It had been suspected that the Corsican Genovese was actually either a local curiosity or was identical to the Bianchetta Genovese/Albarola or the Bosco of Liguria, but this team was able to show that none of these hypotheses were true. Though the three grapes share some morphological similarities, it doesn't look like any of them have any first degree relationships with one another, though Bosco and Albarola appear to be more closely related to one another than either is to Scimiscià.

The last published agricultural census for Italy was carried out before Scimiscià was added to the national register of varieties, so there currently is no figure on total plantings of the grape in Italy (though one imagines that the total is probably pretty minuscule). According to this site, the Çimixà and Scimiscià names are dialectical variants of one another, and both refer to bedbugs because the vine apparently has these spots on it that look like bedbug bites, which is not very appetizing at all. Under the name Genovese, Scimiscià can be found in some Corsican wines, but is pretty much used as a blending grape there. As Frate Pelato, the grape is occasionally used in the blends of the Cinque Terre. There are a handful of Ligurian producers making varietal wines from the grape, and nearly all of them use either the Çimixà or the Scimiscià name for their products.

Bisson chooses to use the Çimixà name on their label, though the wine itself is called "L'Antico." I paid about $30 for my bottle from MCF Rare Wine in New York. I am not sure whether any Italian DOC allows for a 100% Çimixà wine, but this was bottled as an IGT, so it's not really a problem. In the glass the wine was a medium lemon gold color. The nose was moderately intense with lovely, delicate aromas of peach, pear, lime, white flowers and chalk. On the palate the wine was on the lighter side of medium with medium acidity. There were flavors of apricot, lime peel, ripe pear, and golden apple with some chalky minerality on the finish. The wine was subtle, delicate and elegant and was really just lovely to drink. It's not a wine to lay down, though, and it had completely unraveled by the next day, but while it held together, it was very pretty. It is a bit on the expensive side, as many wines from Liguria tend to be, but it's a really unique drinking experience and I don't feel slighted by the price at all.

A few months ago, Tony asked if I had ever heard of a grape called Çimixà from Liguria. Çimixà was definitely a new one on me, and a cursory glance on the internet revealed virtually no information the grape. I saw that Bisson, whose wines I had featured in some prior posts, and whose portfolio seems to be pretty well represented in the Boston area, made a varietal Çimixà, so I set about trying to track a bottle down. I asked around locally to see if anybody could get their hands on some, and came up empty. Not only that, but none of the guys I asked about ordering the wine had ever even heard of it, and these guys are pretty tough to stump. I was now getting more and more anxious to get my hands on a bottle. Tony pointed me in the direction of MCF Rare Wine in New York City, who had about half a dozen bottles in stock and who was willing to sell a bottle to me (all legally, of course).

Though I pulled the cork on my bottle a month or so ago, I've been quietly dreading having to write this post because, as I mentioned above, I wasn't able to find any information at all about Çimixà when I had previously searched online, and a new Google search didn't really get me very much new information either. I went to look the grape up in Wine Grapes, and began to get despondent when I didn't see an entry under Çimixà, so I checked the index and found that it was listed under the name Scimiscià. I know I was a little harsh on Wine Grapes in my review of that book, and I still stand by my criticisms, but it is really an excellent reference work and is very helpful for situations just like this one. Their entry on the grape indicates that it is one of those grapes (like Pugnitello or Nascetta or Pecorino, etc) that was on the brink of extinction, but was rescued by a gentleman named Marco Baciagalupo, a pastry chef from Genoa, Liguria. In the 1970's, Marco gathered together about 500 vines that were purported to be Çimixà and planted them all together in a single plot. A local cooperative took over the job of caring for these vines in the 1990's, and by 2003, the grape was included in the national register of varieties in Italy.

Eagle-eyed readers may note that the picture I've included with this post is for a grape called Genovese, and not Çimixà or Scimiscià. The reason for that is that a study done in 2009 found that the Scimiscià of Liguria was not only the same as the grape known as Frate Pelato in the Cinque Terre, but was also the same as the Genovese of Corsica. It had been suspected that the Corsican Genovese was actually either a local curiosity or was identical to the Bianchetta Genovese/Albarola or the Bosco of Liguria, but this team was able to show that none of these hypotheses were true. Though the three grapes share some morphological similarities, it doesn't look like any of them have any first degree relationships with one another, though Bosco and Albarola appear to be more closely related to one another than either is to Scimiscià.

The last published agricultural census for Italy was carried out before Scimiscià was added to the national register of varieties, so there currently is no figure on total plantings of the grape in Italy (though one imagines that the total is probably pretty minuscule). According to this site, the Çimixà and Scimiscià names are dialectical variants of one another, and both refer to bedbugs because the vine apparently has these spots on it that look like bedbug bites, which is not very appetizing at all. Under the name Genovese, Scimiscià can be found in some Corsican wines, but is pretty much used as a blending grape there. As Frate Pelato, the grape is occasionally used in the blends of the Cinque Terre. There are a handful of Ligurian producers making varietal wines from the grape, and nearly all of them use either the Çimixà or the Scimiscià name for their products.

Bisson chooses to use the Çimixà name on their label, though the wine itself is called "L'Antico." I paid about $30 for my bottle from MCF Rare Wine in New York. I am not sure whether any Italian DOC allows for a 100% Çimixà wine, but this was bottled as an IGT, so it's not really a problem. In the glass the wine was a medium lemon gold color. The nose was moderately intense with lovely, delicate aromas of peach, pear, lime, white flowers and chalk. On the palate the wine was on the lighter side of medium with medium acidity. There were flavors of apricot, lime peel, ripe pear, and golden apple with some chalky minerality on the finish. The wine was subtle, delicate and elegant and was really just lovely to drink. It's not a wine to lay down, though, and it had completely unraveled by the next day, but while it held together, it was very pretty. It is a bit on the expensive side, as many wines from Liguria tend to be, but it's a really unique drinking experience and I don't feel slighted by the price at all.

Friday, December 7, 2012

Vidal Blanc - Massachusetts and Finger Lakes, New York, USA

Vidal Blanc is either a grape you've never heard of or a grape that you can't get away from, depending on where you live and, to some extent, how you shop. Here in the cold northeastern United States, Vidal is seemingly everywhere, but only if you go to the local wineries to sample their wares. It is still difficult to find on store shelves in the Boston area, and if you do run across one in your local shop, chances are it's a Canadian ice wine. I've made many visits to most of the wineries in Massachusetts and to many others throughout New England, though, and I came across so many Vidal Blanc based wines that, for awhile, I thought that perhaps Vidal Blanc wasn't really a fringe grape. I was surprised, though, when I saw some of the planting statistics for the grape. Canada certainly leads the way in Vidal plantings at nearly 2,000 acres, much of which is ultimately used to make ice wine, but I was shocked to learn that Virginia actually leads the way in US plantings of Vidal at 150 acres,* followed closely by Michigan (145 acres) and Missouri (118 acres) before dropping off precipitously to 35 acres in Indiana and 32 in Illinois. Clearly the vine isn't quite as ubiquitous as it seemed to me, so I decided to write about the Vidal Blanc grape itself and a few local wines that I've come across recently.

Vidal Blanc was created in 1930 by Jean-Louis Vidal, a French grape breeder who was trying to create new grapes for Cognac production. Jean-Louis created Vidal Blanc by crossing Ugni Blanc (aka Trebbiano Toscano, one the grapes still most commonly used to make Cognac) with Rayon d'Or, which is itself a hybrid created by our old friend Albert Seibel by crossing two other Seibel hybrid grapes together (Seibel 405 & 2007, for those filling out your pedigree charts at home). Jean-Louis Vidal created several thousand different grapes throughout his career, but Vidal Blanc has definitely been the most successful and is easily the most widely cultivated grape bred by him. Even though the grape was created in France by a French breeder, it is virtually non-existent there today.

Vidal Blanc came to the New World, or at least to Canada, in 1945, when a man named Adhémar de Chaunac imported 35 French hybrids (one of which was Vidal Blanc) and four vinifera varieties into Canada. De Chaunac was the technical director at TG Bright winery in Niagara Falls, and he was looking for new grapes to grow at his winery other than the foxy native American varieties that had been widely used to that point in Canadian wine history. Most plantings with vinifera varieties had not gone well, as they were generally unable to tolerate the harsh Canadian winters, so De Chaunac was hoping to find some cold hardy varieties in this group that could withstand the difficult climate and still make European-style wines. Test plots were planted and wine making trials began and by the 1960's, the hybrid grapes that showed the most potential were gaining ground in the Canadian planting statistics. Maréchal Foch, Seyval Blanc, Verdelet, De Chaunac and Vidal Blanc were the most popular, and many of those grapes are still somewhat widely planted throughout Canada.

Vidal Blanc is perhaps best known for the ice wines created from it in many parts of Canada and the northeastern United States. As mentioned in my post on an ice wine made from Cabernet Sauvignon in Canada, true ice wines are made from grapes that are left on the vine well after the regular harvest and allowed to freeze there. The frozen grapes are harvested in the dead of night (to prevent their thawing) and are pressed while still frozen. What happens when a grape freezes is that much of the water in the grape turns to ice, but most of the sugar doesn't freeze, so when you press the frozen grapes, the solid ice stays behind, but a concentrated, sugary syrup comes out. This syrup is then partially fermented, since it is impossible to convert all of that sugar into alcohol, and the result is a rich, lusciously sweet wine.

It may seem like a simple thing to just leave some grapes on the vine and harvest the frozen juice, but not all grapes are suited to making good ice wine. First of all, the grapes need to stay on the vine a very long time, and as grapes hang on the vine and ripen, they tend to lose their acidity. Acidity is key in sweet wines, though, since without it, wines just taste syrupy and cloyingly sweet. Secondly, the longer grapes hang on the vine, the greater the chance that they can be damaged either by diseases such as molds or mildews, by insects or birds, or just from the wind and weather. Thick grape skins help protect grapes while they are waiting for the first freeze to arrive, so while thin-skinned varieties like Semillon are valued for the production of botrytised sweet wines (since their thin skins allow the botrytis to more easily infect the grapes), thick skinned varieties are preferred for the production of ice wines. Vidal Blanc happens to have thick skins and relatively high acidity, which makes it an ideal grape for ice wine production.

When I visited the Finger Lakes region of New York a year or so ago, I picked up a bottle of the 2009 Vidal Ice from Standing Stone Vineyards for about $25 for a half bottle. This is not a true ice wine, since the grapes were picked and then later frozen before ultimately being pressed. In the glass it was a light tawny gold color. The nose was fairly intense with aromas of honey, dried apricot, quince, baked apple and pineapple. On the palate the wine was on the fuller side of medium with fairly high acidity. It was lusciously sweet with flavors of honey, apricot, baked pineapple, and orange creme with a bright, zippy vein of tart green apple running through it. It was dense and rich, but it was also lively and snappy thanks to the fresh acidity. I found it really well balanced and enjoyed it an awful lot. I've bought Vidal Blanc based ice wines from Canada before and have paid almost $100 for half bottles of some of them, so at only $25 per half bottle, this is a tremendous value.

In his Wines of Canada (which I've used extensively throughout this post), John Schreiner gives the following quote about Vidal Blanc from the CEO of the Canadian wine powerhouse Vincor, Donald Triggs: "Vidal is in that magical area of not making a really great table wine but a phenomenal Icewine." While Canada tends to focus on making ice wine from their Vidal grapes, most American producers make dry table wines from theirs, and I was able to pick up a few local examples recently and test whether Triggs' assessment of its potential as a table wine grape was accurate or not.

The first bottle that I tried was the 2010 Vidal Blanc from Running Brook Vineyards in North Darthmouth, Massachusetts, which set me back about $13. Running Brook was founded by Pedro Teixeira and Manuel Morais, both of whom spent much of their separate childhoods in the Azores islands of Portugal. Manuel started his first vineyard in 1975 and was one of the first people to grow grapes commercially in New England. Pedro was actually his dentist and the two quickly realized that they both shared a passion for the vine and wine and decided to go into business together. They opened Running Brook Vineyards in 1998, according to their website, though their labels say "Est. 2000."

In the glass, this wine was a medium lemon gold color. The nose was moderately intense with pear, banana, grapefruit and honeysuckle flower aromas. On the palate the wine was on the fuller side of medium with medium acidity. It was medium sweet with flavors of honeyed pink grapefruit, poached pear, candied pineapple and coconut. The image that sprang to mind while drinking this wine was a Dole fruit cup, meaning it was fruity and sweet with a variety of flavors going on, but was still kind of flat and ultimately not that exciting. Fans of simple, sweet white wines will find a lot to like here, especially for the price, but it's not really my thing.

The second wine that I tried was the 2009 Travessia Vidal Blanc, which I picked up for about $10 (not at the winery, but rather at the Bin Ends discount store in Braintree...the 2011 Vidal Blanc seems to cost about $15 at the winery itself). Travessia is an "urban winery" located in downtown New Bedford, Massachusetts, which is owned by Marco Montez, who also makes all the wine. Marco doesn't own any vineyards, but rather he buys most of his grapes from Running Brook and from Westport Rivers in Massachusetts. He does make wine from California and from Washington St. grapes, but he insists that his wines labeled as being from Massachusetts are made with 100% Massachusetts fruit.

In the glass, this wine was a medium lemon gold color. The nose was reserved with reserved aromas of honey, pineapple and peach. On the palate, the wine was medium bodied with high acidity. It tasted off-dry with flavors of green apple, under-ripe pineapple and lime with just a touch of peachiness. It was somewhat tart with sharp acidity, but I found that I preferred this to the flatter Running Brook wine. Both were somewhat Riesling-like, but the Running Brook was definitely broader and more generous, while the Travessia was leaner, sharper and more austere. To some extent, this could be a vintage issue, since 2010 was very hot in Massachusetts, and many wineries found themselves with very ripe grapes. 2009 was a more typical, cooler year, so the grapes probably weren't quite as ripe as in 2010, and as a result, the acidity is a bit higher and the fruits aren't quite as generous. Whatever the reason, this wine is a great value at only $10, and would still be a good value at $15 as well.

*These statistics are taken from Wine Grapes, which indicates that New York has substantial plantings, but gives no acreage for them. I haven't been able to find any specific numbers for New York myself, since most sources online only list the top 5 or so hybrid grapes grown in New York, and Vidal apparently doesn't crack that list. Further, New York seems to measure things in terms of tons of grapes processed rather than acres under vine, so even if I could find a number for Vidal, I'm not sure how enlightening it would actually be.

Vidal Blanc was created in 1930 by Jean-Louis Vidal, a French grape breeder who was trying to create new grapes for Cognac production. Jean-Louis created Vidal Blanc by crossing Ugni Blanc (aka Trebbiano Toscano, one the grapes still most commonly used to make Cognac) with Rayon d'Or, which is itself a hybrid created by our old friend Albert Seibel by crossing two other Seibel hybrid grapes together (Seibel 405 & 2007, for those filling out your pedigree charts at home). Jean-Louis Vidal created several thousand different grapes throughout his career, but Vidal Blanc has definitely been the most successful and is easily the most widely cultivated grape bred by him. Even though the grape was created in France by a French breeder, it is virtually non-existent there today.

Vidal Blanc came to the New World, or at least to Canada, in 1945, when a man named Adhémar de Chaunac imported 35 French hybrids (one of which was Vidal Blanc) and four vinifera varieties into Canada. De Chaunac was the technical director at TG Bright winery in Niagara Falls, and he was looking for new grapes to grow at his winery other than the foxy native American varieties that had been widely used to that point in Canadian wine history. Most plantings with vinifera varieties had not gone well, as they were generally unable to tolerate the harsh Canadian winters, so De Chaunac was hoping to find some cold hardy varieties in this group that could withstand the difficult climate and still make European-style wines. Test plots were planted and wine making trials began and by the 1960's, the hybrid grapes that showed the most potential were gaining ground in the Canadian planting statistics. Maréchal Foch, Seyval Blanc, Verdelet, De Chaunac and Vidal Blanc were the most popular, and many of those grapes are still somewhat widely planted throughout Canada.

Vidal Blanc is perhaps best known for the ice wines created from it in many parts of Canada and the northeastern United States. As mentioned in my post on an ice wine made from Cabernet Sauvignon in Canada, true ice wines are made from grapes that are left on the vine well after the regular harvest and allowed to freeze there. The frozen grapes are harvested in the dead of night (to prevent their thawing) and are pressed while still frozen. What happens when a grape freezes is that much of the water in the grape turns to ice, but most of the sugar doesn't freeze, so when you press the frozen grapes, the solid ice stays behind, but a concentrated, sugary syrup comes out. This syrup is then partially fermented, since it is impossible to convert all of that sugar into alcohol, and the result is a rich, lusciously sweet wine.

It may seem like a simple thing to just leave some grapes on the vine and harvest the frozen juice, but not all grapes are suited to making good ice wine. First of all, the grapes need to stay on the vine a very long time, and as grapes hang on the vine and ripen, they tend to lose their acidity. Acidity is key in sweet wines, though, since without it, wines just taste syrupy and cloyingly sweet. Secondly, the longer grapes hang on the vine, the greater the chance that they can be damaged either by diseases such as molds or mildews, by insects or birds, or just from the wind and weather. Thick grape skins help protect grapes while they are waiting for the first freeze to arrive, so while thin-skinned varieties like Semillon are valued for the production of botrytised sweet wines (since their thin skins allow the botrytis to more easily infect the grapes), thick skinned varieties are preferred for the production of ice wines. Vidal Blanc happens to have thick skins and relatively high acidity, which makes it an ideal grape for ice wine production.

When I visited the Finger Lakes region of New York a year or so ago, I picked up a bottle of the 2009 Vidal Ice from Standing Stone Vineyards for about $25 for a half bottle. This is not a true ice wine, since the grapes were picked and then later frozen before ultimately being pressed. In the glass it was a light tawny gold color. The nose was fairly intense with aromas of honey, dried apricot, quince, baked apple and pineapple. On the palate the wine was on the fuller side of medium with fairly high acidity. It was lusciously sweet with flavors of honey, apricot, baked pineapple, and orange creme with a bright, zippy vein of tart green apple running through it. It was dense and rich, but it was also lively and snappy thanks to the fresh acidity. I found it really well balanced and enjoyed it an awful lot. I've bought Vidal Blanc based ice wines from Canada before and have paid almost $100 for half bottles of some of them, so at only $25 per half bottle, this is a tremendous value.

In his Wines of Canada (which I've used extensively throughout this post), John Schreiner gives the following quote about Vidal Blanc from the CEO of the Canadian wine powerhouse Vincor, Donald Triggs: "Vidal is in that magical area of not making a really great table wine but a phenomenal Icewine." While Canada tends to focus on making ice wine from their Vidal grapes, most American producers make dry table wines from theirs, and I was able to pick up a few local examples recently and test whether Triggs' assessment of its potential as a table wine grape was accurate or not.

The first bottle that I tried was the 2010 Vidal Blanc from Running Brook Vineyards in North Darthmouth, Massachusetts, which set me back about $13. Running Brook was founded by Pedro Teixeira and Manuel Morais, both of whom spent much of their separate childhoods in the Azores islands of Portugal. Manuel started his first vineyard in 1975 and was one of the first people to grow grapes commercially in New England. Pedro was actually his dentist and the two quickly realized that they both shared a passion for the vine and wine and decided to go into business together. They opened Running Brook Vineyards in 1998, according to their website, though their labels say "Est. 2000."

In the glass, this wine was a medium lemon gold color. The nose was moderately intense with pear, banana, grapefruit and honeysuckle flower aromas. On the palate the wine was on the fuller side of medium with medium acidity. It was medium sweet with flavors of honeyed pink grapefruit, poached pear, candied pineapple and coconut. The image that sprang to mind while drinking this wine was a Dole fruit cup, meaning it was fruity and sweet with a variety of flavors going on, but was still kind of flat and ultimately not that exciting. Fans of simple, sweet white wines will find a lot to like here, especially for the price, but it's not really my thing.

The second wine that I tried was the 2009 Travessia Vidal Blanc, which I picked up for about $10 (not at the winery, but rather at the Bin Ends discount store in Braintree...the 2011 Vidal Blanc seems to cost about $15 at the winery itself). Travessia is an "urban winery" located in downtown New Bedford, Massachusetts, which is owned by Marco Montez, who also makes all the wine. Marco doesn't own any vineyards, but rather he buys most of his grapes from Running Brook and from Westport Rivers in Massachusetts. He does make wine from California and from Washington St. grapes, but he insists that his wines labeled as being from Massachusetts are made with 100% Massachusetts fruit.

In the glass, this wine was a medium lemon gold color. The nose was reserved with reserved aromas of honey, pineapple and peach. On the palate, the wine was medium bodied with high acidity. It tasted off-dry with flavors of green apple, under-ripe pineapple and lime with just a touch of peachiness. It was somewhat tart with sharp acidity, but I found that I preferred this to the flatter Running Brook wine. Both were somewhat Riesling-like, but the Running Brook was definitely broader and more generous, while the Travessia was leaner, sharper and more austere. To some extent, this could be a vintage issue, since 2010 was very hot in Massachusetts, and many wineries found themselves with very ripe grapes. 2009 was a more typical, cooler year, so the grapes probably weren't quite as ripe as in 2010, and as a result, the acidity is a bit higher and the fruits aren't quite as generous. Whatever the reason, this wine is a great value at only $10, and would still be a good value at $15 as well.

*These statistics are taken from Wine Grapes, which indicates that New York has substantial plantings, but gives no acreage for them. I haven't been able to find any specific numbers for New York myself, since most sources online only list the top 5 or so hybrid grapes grown in New York, and Vidal apparently doesn't crack that list. Further, New York seems to measure things in terms of tons of grapes processed rather than acres under vine, so even if I could find a number for Vidal, I'm not sure how enlightening it would actually be.

Wednesday, December 5, 2012

Colorino - Tuscany, Italy

Colorino is one of those grapes that the average wine drinker has almost certainly encountered, but is probably not aware of it. Colorino was historically very important in the production of Chianti, and if you've sampled a few different Chiantis in your lifetime, you've almost certainly had one with a little dollop of Colorino thrown in. Colorino has been a traditional part of the Chianti blend for many years, though it rarely makes up more than 5-10% of the final product. As you might expect from its name, the primary thing Colorino brings to the table is deep color, which it is able to impart even at such small concentrations. Its contribution to the Chianti blend has been compared to that of Petit Verdot in Bordeaux, and, like Petit Verdot, some producers have decided to see whether Colorino is interesting enough to make varietal wines from. I was able to pick one up recently, but before I get into that, let's take a little closer look at the Colorino grape itself.

As mentioned above, Colorino has long been valued for its contribution to the Chianti blend, especially for those producers who utilized the governo method. In the governo method, some of the grapes harvested in September and October were set aside and not pressed with the others. These grapes were allowed to dry out for several months before being pressed in mid to late November. As you might expect, some grapes are able to withstand this drying process better than others, and Colorino is particularly well suited to it. This concentrated, sweet juice was then added to the vats of juice that had just finished its primary alcoholic fermentation, which caused the fermentation to start up again. While this had the immediate effect of increasing the final alcohol content, the main reason for this practice was that this second fermentation often kicked off malolactic fermentation as well, which, in the days before bacterial inoculation, was not always so easy to start in a wine made from a high-acid variety like Sangiovese. The governo process made the wines drinkable much earlier than they otherwise would be, and was more heavily used when Chianti was seen as an easy-drinking, every day/every meal kind of wine. With the more recent focus on quality and creating age-worthy red wines, the governo process has fallen out of favor. Colorino continues to be used in the Chianti blend, though, for its ability to lend color to the final wine, and for a time, its popularity began to rise as many producers fought against the increasing presence of Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot in Tuscan vineyards and wines, though the gradual acceptance of the international varieties in Tuscany has caused its popularity to wane once more.

You may not be surprised to learn that a grape name like Colorino has come to be used for several different grape varieties over the years*. A study done in 1996 analyzed four different grapes known as Colorino and found that not only were they each different grape varieties, but at least one of them didn't seem to even be related to the other three at all. The outlier of the group was called Colorino Americano, while the other three were known as Colorino del Valdarno, Colorino di Pisa and Colorino di Lucca. In 2008, another study (citation 1) analyzed Colorino di Pisa and Colorino di Lucca along with a handful of other Tuscan vines and showed that the two Colorinos were in fact distinct and possibly have a parent/offspring relationship with one another. To add to the confusion, the VIVC considers Colorino di Valdarno, Colorino di Lucca and Colorino Pisano to be the same variety and doesn't have an entry for Colorino di Americano at all. They further list three other Colorinos that are different from the three mentioned above, calling them Colorino Dolce, Forte and Nostrale respectively. I have not been able to find any other information on these three varieties of Colorino, so I'm not sure how they fit in with the others or even how widely cultivated they may be. Wine Grapes tells us that the most common variety of Colorino is Colorino del Valdarno, but since it doesn't appear that the Italian authorities differentiate between these vines, any or all of the four (or seven) Colorinos could be present in your bottle. The latest Italian agricultural census (2000) indicated that there were 436 hectares planted to Colorino, and one assumes that this figure includes the various Colorino varieties altogether.

I was able to find a bottle of the 2005 La Spinetta "Il Colorino" at Panzano in Southborough for around $34. In the glass the wine was a deep, opaque purple ruby color. The nose was moderately intense with stewed black cherry, black plum, smoke and charcoal aromas. On the palate the wine was on the fuller side of medium with fairly high acidity and medium tannins. There were flavors of black cherry, blackberry, sour cherry and wild blueberry fruits along with some licorice, smoke, char, and earth. The wine was mostly dark and dense, but it had a nice bit of tart freshness from the sour cherry and blueberry flavors that kept it lively and interesting. It is often the case that one understands quickly why blending grapes are rarely seen in a starring role when one finds a varietal wine comprised of these grapes, but I had the complete opposite reaction when tasting this wine. Rather, I found myself wondering why more people wouldn't try to make wines like this, as it was complex, interesting and very tasty to boot. The price tag looks a little steep at first blush, but I wouldn't have any qualms about paying that amount again for this wine. I thoroughly enjoyed it and would definitely pick it up again if I ever run across it.

*Some sources have indicated that the Ancellotta of Emilia-Romagna and Colorino are the same grape, but it doesn't look like that's so. While I wasn't able to find any specific studies that compared the two grapes, a recent study conducted by a French team (citation 2) analyzed over 4000 different grape accessions in a particular collection. Though there is no table with all of the data shown, a later parentage study (citation 3) by many of the same team members gave a list of the 2300+ grapes used, which was culled from the results of the earlier study. Ancellotta and Colorino are listed separately, which seems to indicate that they are genetically distinct from one another. Just which Colorino variety was used, though, is unclear.

Citations

1) Vignani, R, Masi, E, Scali, M, Milanesi, C, Scalabreli, G, Wang, W, Sensi, E, Paolucci, E, Percoco, G & Cresti, M. 2008. A critical evaluation of SSRs analysis applied to Tuscan grape (Vitis vinifera L.) germplasm. Advances in Horticultural Science. 22(1), pp 33-37.

2) Lacau, et al. 2011. High throughput analysis of grape genetic diversity as a tool for germplasm collection management. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 122(6), pp 1233-1245.

3) Lacombe, T., Boursiquot, J.M., Laucou, V., Di Vecchi-Staraz, M., Peros, J.P., & This, P. 2012. Large scale parentage analysis in an extended set of grapevine cultivars (Vitis vinifera L.). Theoretical and Applied Genetics. In press.

As mentioned above, Colorino has long been valued for its contribution to the Chianti blend, especially for those producers who utilized the governo method. In the governo method, some of the grapes harvested in September and October were set aside and not pressed with the others. These grapes were allowed to dry out for several months before being pressed in mid to late November. As you might expect, some grapes are able to withstand this drying process better than others, and Colorino is particularly well suited to it. This concentrated, sweet juice was then added to the vats of juice that had just finished its primary alcoholic fermentation, which caused the fermentation to start up again. While this had the immediate effect of increasing the final alcohol content, the main reason for this practice was that this second fermentation often kicked off malolactic fermentation as well, which, in the days before bacterial inoculation, was not always so easy to start in a wine made from a high-acid variety like Sangiovese. The governo process made the wines drinkable much earlier than they otherwise would be, and was more heavily used when Chianti was seen as an easy-drinking, every day/every meal kind of wine. With the more recent focus on quality and creating age-worthy red wines, the governo process has fallen out of favor. Colorino continues to be used in the Chianti blend, though, for its ability to lend color to the final wine, and for a time, its popularity began to rise as many producers fought against the increasing presence of Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot in Tuscan vineyards and wines, though the gradual acceptance of the international varieties in Tuscany has caused its popularity to wane once more.

You may not be surprised to learn that a grape name like Colorino has come to be used for several different grape varieties over the years*. A study done in 1996 analyzed four different grapes known as Colorino and found that not only were they each different grape varieties, but at least one of them didn't seem to even be related to the other three at all. The outlier of the group was called Colorino Americano, while the other three were known as Colorino del Valdarno, Colorino di Pisa and Colorino di Lucca. In 2008, another study (citation 1) analyzed Colorino di Pisa and Colorino di Lucca along with a handful of other Tuscan vines and showed that the two Colorinos were in fact distinct and possibly have a parent/offspring relationship with one another. To add to the confusion, the VIVC considers Colorino di Valdarno, Colorino di Lucca and Colorino Pisano to be the same variety and doesn't have an entry for Colorino di Americano at all. They further list three other Colorinos that are different from the three mentioned above, calling them Colorino Dolce, Forte and Nostrale respectively. I have not been able to find any other information on these three varieties of Colorino, so I'm not sure how they fit in with the others or even how widely cultivated they may be. Wine Grapes tells us that the most common variety of Colorino is Colorino del Valdarno, but since it doesn't appear that the Italian authorities differentiate between these vines, any or all of the four (or seven) Colorinos could be present in your bottle. The latest Italian agricultural census (2000) indicated that there were 436 hectares planted to Colorino, and one assumes that this figure includes the various Colorino varieties altogether.

I was able to find a bottle of the 2005 La Spinetta "Il Colorino" at Panzano in Southborough for around $34. In the glass the wine was a deep, opaque purple ruby color. The nose was moderately intense with stewed black cherry, black plum, smoke and charcoal aromas. On the palate the wine was on the fuller side of medium with fairly high acidity and medium tannins. There were flavors of black cherry, blackberry, sour cherry and wild blueberry fruits along with some licorice, smoke, char, and earth. The wine was mostly dark and dense, but it had a nice bit of tart freshness from the sour cherry and blueberry flavors that kept it lively and interesting. It is often the case that one understands quickly why blending grapes are rarely seen in a starring role when one finds a varietal wine comprised of these grapes, but I had the complete opposite reaction when tasting this wine. Rather, I found myself wondering why more people wouldn't try to make wines like this, as it was complex, interesting and very tasty to boot. The price tag looks a little steep at first blush, but I wouldn't have any qualms about paying that amount again for this wine. I thoroughly enjoyed it and would definitely pick it up again if I ever run across it.

*Some sources have indicated that the Ancellotta of Emilia-Romagna and Colorino are the same grape, but it doesn't look like that's so. While I wasn't able to find any specific studies that compared the two grapes, a recent study conducted by a French team (citation 2) analyzed over 4000 different grape accessions in a particular collection. Though there is no table with all of the data shown, a later parentage study (citation 3) by many of the same team members gave a list of the 2300+ grapes used, which was culled from the results of the earlier study. Ancellotta and Colorino are listed separately, which seems to indicate that they are genetically distinct from one another. Just which Colorino variety was used, though, is unclear.

Citations

1) Vignani, R, Masi, E, Scali, M, Milanesi, C, Scalabreli, G, Wang, W, Sensi, E, Paolucci, E, Percoco, G & Cresti, M. 2008. A critical evaluation of SSRs analysis applied to Tuscan grape (Vitis vinifera L.) germplasm. Advances in Horticultural Science. 22(1), pp 33-37.

2) Lacau, et al. 2011. High throughput analysis of grape genetic diversity as a tool for germplasm collection management. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 122(6), pp 1233-1245.

3) Lacombe, T., Boursiquot, J.M., Laucou, V., Di Vecchi-Staraz, M., Peros, J.P., & This, P. 2012. Large scale parentage analysis in an extended set of grapevine cultivars (Vitis vinifera L.). Theoretical and Applied Genetics. In press.

Monday, December 3, 2012

Albana di Romagna - Emilia-Romagna, Italy

Though the history of viniculture and viticulture goes back several thousand years, the histories of individual grapes tend to be measure on the scale of hundreds of years at the most. There are several good reasons for this. The most important reason is that the craze for varietal wines and the consumer and winemaker focus on individual grape varieties is a very recent phenomenon. Wines were traditionally given names related to their geography, and the grapes that went into making those wines was of secondary importance at best. The linking of individual grape varieties with particular places didn't become a legal issue until the last hundred or so years when the various appellation laws began to take effect throughout Europe. While individual grape varieties may have been associated with famous wine growing regions in the distant past, there was nothing (or very little) forcing any of those growers to continue to grow those grapes in those regions other than tradition.

Another, more obvious reason for the lack of long historical records for individual grapes is that grape names have tended not to be very stable throughout history. The lands of Europe have changed hands many times over the past few thousand years and each new wave of conquerors brought their own languages and their own attitudes towards wine making and wine drinking. The mix of materials, languages and cultures made it difficult for a stable vocabulary to develop so even if a particular grape variety has been in continuous cultivation for a thousand years, it would be easy to lose track of it through the historical record as that record shifted from conqueror to conqueror and from language to language. Throw in the lack of a consistent and thorough historical record for all wine making regions throughout history and the lack of a unified ampelography, and you end up running into a lot of trouble when you try to trace an individual grape very far back through the written histories.

Some grapes do have long historical roots, though, and Albana is one of them. The first written record of a grape known as Albana comes to us from a work written in 1305 AD. Pietro de Crescenzi, a Medieval agricultural writer, writes of Albana that it makes "a powerful wine with an excellent taste." You can find some variation on this theme in just about any source you pick up that mentions the grape, though I've often wondered how anyone can be sure that the grape called Albana 700 years ago is the same as the grape currently known by that name. This becomes an even more troubling question when you take a look at the two etymological reasons given for the grape's name. The most common reason given is that the grape's name comes from the Latin word alba, meaning "white," and it was given its name because of its exemplary stature in comparison with other white grapes. The second explanation for the grape's name is that it was originally cultivated around the Alban Hills of Lazio and was named for them*. Both explanations seem to allow for the possibility of a lot of confusion with similarly named grapes, and I would be very surprised if it turned out that Crescenzi's Albana and ours were the same grape. Since there's probably no way to say for sure, though, we should probably just note our skepticism and move along.

What we can say for sure about Albana is that it is an important piece of the Garganega family tree. Garganega is the great white grape of Soave, and recent studies have shown that it has a parent/offspring relationship with a staggering number and variety of grapes throughout Italy. One of those grapes is Albana, though Garganega also has a parent/offspring relationship with Catarratto, Trebbiano Toscana and Malvasia di Candia, among others. What is really shocking about these findings is the geographical dispersion of these grapes, as they can be found from the Veneto in the northeast to Emilia Romagna in the center-west, all the way down to the island of Sicily in the south. It isn't clear whether Garganega is the parent to all of the varieties listed or whether one of them is one of its parents, which means that Albana is either a grandparent to the others (if it happens to be a parent to Garganega), or is a half-sibling to them and possibly a grandchild of one.