Roscetto is one of those rare Italian grapes that is grown in a single place and made by a single producer and is not produced anywhere else in the world. If you've found this page, you've probably gone through quite a few pages that have written about the grape and every single one of them mentions a single producer and winemaker: Riccardo Cotarella of Falesco Winery. Wikipedia comes up empty, Jancis Robinson's Oxford Companion of Wine makes no mention, and even the VIVC (Vitis International Variety Catalog) has no results for Roscetto. The only information that is available is coming from the winery, either in articles written about the winery or winemaker or from the winery's website itself. Normally, I like to use a variety of sources so I can check them against one another, but in this case, not only is all the wine on earth made from this grape coming from a single estate, but seemingly all the information on earth about the same grape is coming from there as well.

So what do we know? Falesco winery has a bottling called Ferentano that is the only 100% varietally bottled Roscetto on earth (some of their Roscetto crop goes into their Est! Est!! Est!!! bottling). According to Falesco, the grape is an ancient variety indigenous to the Lazio region (and more specifically, Montefiascone, a town in northeastern Lazio about 100 km from Rome). It is a white grape that turns a little pinkish as it ripens. It has thick skins and after the grapes are crushed, the skins and juice are held together at a very low temperature for awhile (a process called cryomaceration) in order to extract the phenolic compounds from the skins. The wine was first bottled by the Falesco winery in the 1998 vintage. And that's about all I can find. There's plenty of information out there about the winery itself, which is perhaps best known for their Merlot bottling called Montiano, though they have a pretty wide variety of offerings. Wine.com informs me that "in 2006, our customers purchased more bottles of wine from Falesco than from any other winery in the world." I don't know how many cases of the Ferentano are produced, but I have found this wine in two different wine shops in the Boston area so I don't think production is down in the cult numbers.

The bottle I was able to pick up was from the 2006 vintage (oddly, both local stores where I've found this wine were from the 2006 vintage). It cost me $12 at Bin Ends, but I picked it up from a sale rack marked 50% off. I believe this usually retails for around $20.

The wine had a rich, gold color in the glass. When I first pulled the cork, the wine had a heady, appley perfume that faded pretty quickly into something fairly neutral with some buttery toast notes. It was rich and full-bodied on the palate with good acidity and a creamy texture. There were ripe apple, buttery toast, lime peel and toasted nut flavors with some vanilla. It was pretty clear that this had seen some oak, and the winery web site confirms that the wine spends four months in oak barriques. I was very pleasantly surprised at how lively this was at five years old. This probably has the stuffing for a few more years in bottle. It's very similar to white Burgundy or some of the more restrained California Chardonnays. I don't know what kind of oak is used here, but it's almost certainly not American, and if you made me choose, I'd guess its mostly new French oak. This is not really the style of white wine I go for, but this was really an exceptional bottle. If you can track this bottle down, definitely give it a shot as it's a very unique grape (even if it is made in an international style).

A blog devoted to exploring wines made from unusual grape varieties and/or grown in unfamiliar regions all over the world. All wines are purchased by me from shops in the Boston metro area or directly from wineries that I have visited. If a reviewed bottle is a free sample, that fact is acknowledged prior to the bottle's review. I do not receive any compensation from any of the wineries, wine shops or companies that I mention on the blog.

Friday, April 29, 2011

Wednesday, April 27, 2011

Teroldego - Trentino and Tuscany, Italy

I'm going to confess something: I'm kind of a geek. I guess anyone who has read more than one of my posts probably could have figured that out, but I'm just going to come right out and say it here. Part of why I love writing this website is that it gives me an outlet for the kind of geekery that I can't really let fly in my everyday life. I love doing the research and learning about the minutiae of these unusual grapes. I love exploring the nooks and crannies of the wine world to try and find hidden treasures and cool stories. Today, for example, I was doing a little bit of background reading to get ready to post about Teroldego when I stumbled across an article in the journal Heredity called "Geneaology of Wine Grape Cultivars" (full citation: Vouillamoz, J., & Grando, M. (2006). Genealogy of wine grape cultivars: ‘Pinot’ is related to ‘Syrah’. Heredity, 97(2), 102-110). I know, this dry, academic reading is what most people use to get through a particularly vicious attack of insomnia, but I love this stuff. My day job is also at a big time research university, so I have full access to a lot of these journals. Anyway, I started to read this article and it's talking about how for many years, scientists would look at the leaf shape of different grape varieties to try to determine the relation between different cultivars. Needless to say, this was a very inexact science. Recent progress in the field of genetics has allowed scientists to use genetic markers to identify parentage and sibling relationships between all these different grapes with much greater accuracy and with many interesting surprises (I'll spare you the excruciating details, but the method is similar to the method that forensic scientists use on DNA samples at crime scenes). So I'm reading through this article and then looking through the references and picking up new articles and I look up and I've got 5 articles printed out in front of me and I figure it's probably time to stop and get to the matter at hand.

So, Teroldego, then. It appears that there may be a sibling relationship between Teroldego and the Pinot family and there is likely a parent/offspring relationship between Teroldego and Lagrein and Marzemino (**UPDATE** Teroldego is definitely one parent of Lagrein, while the other is Schiava Gentile, according to: Cipriani, G. et al. The SSR-based molecular profile of 1005 grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) accessions uncovers new synonymy and parentages, and reveals a large admixture amongst varieties of different geographic origin. 2010. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 121: 1569-1585.). It also turns out that Teroldego is a full sibling (meaning it has the same two parent vines) to a grape called Dureza, which is one of the parent grapes of Syrah. This is interesting in light of a comment from Jim Clendenen of Au Bon Climat winery in California which is quoted in Oz Clarke's Grapes and Wines. Clarke has Clarendon saying that California should have planted Teroldego rather than Merlot and Barbera and, furthermore, it is his belief that if Teroldego were planted on the slopes of Crozes-Hermitage rather than Syrah then the wine there would be greatly improved. Bold talk indeed. Au Bon Climat is primarily a Pinot Noir producer and their terroir isn't necessarily conducive to the Teroldego grape, but I believe that they do have a little Teroldego under vine (according to Eric Asimov of the NYT), though I don't know if they actually bottle and sell any of it (there is no mention on their website). It is possible in California to blend up to 25% of other grape varietals into a single-varietal bottling in California without mentioning it on the label, so its possible that they could use those grapes for that purpose. Some California producers are notorious for adding high color wines like Syrah to their Pinot bottlings for added color and depth so it wouldn't necessarily surprise me, but I'm certainly not going to accuse the winemaker of doing that based on a hunch and some anecdotal evidence.

Teroldego's home is Trentino in the Trentino-Alto Adige region of Italy. We've spent a little time in the Alto Adige visiting with Schiava. Trentino is the southerly portion of this region where the Germanic/Austrian influence isn't quite as pronounced. There are references to Teroldego from Trentino mentioned as far back as the 15th Century. The grape is well suited to warm weather, which may seem a little odd for northern Italy, but they have some areas in the valleys and river basins where the grape can get all the sun and warmth that it needs. It is a thin-skinned variety that produces a deeply colored wine, somehow. There are competing theories about the origin of the name of the grape. I've read that a court in Vienna once called the wine "The Gold of the Tyrol," and somehow that ended up as "Teroldego." I've also read that it has more to do with the wire harnesses, or "tirelles" used to trellis the vine. Matt Kramer, in his Making Sense of Italian Wine contends that that the name derives from the Gernman word teer which means "tar," a flavor which Teroldego can sometimes take on. Take your pick, I guess.

The first wine that I was able to try was the 2005 Teroldego Rotalino (the official DOC name of the region in Trentino where most Teroldego is grown, named for the gravelley river bottom plain called Campo Rotalino near the Adige river) Riserva from Mezzacorona. I was able to pick this up from my friends at Bin Ends for about $20. In the glass, the wine was a dense purple ruby color nearly all the way to the rim. The nose was full of smoky black cherry and black plum with some blackberry and blueberry. On the palate, the wine was close to full bodied with fairly high acid and very little tannin. The grape can be tannic in its youth, but at 6 years out, most of that seemed to be pretty well integrated. There were flavors of black plum, smoky earth, tart cherries and stewed blackberries. The wine was much fruitier and exciting on the nose than on the palate. The finish is kind of abrupt as the fruit really falls off rather than fade away. People have mixed feelings about the age-ability of Teroldego, and after this bottle, I can understand the misgivings.

Talk to people familiar with the grape and they'll tell you that Teroldego grows in Trentino and nowhere else; in fact, Bastianich and Lynch (in their Vino Italiano) quote Elisabetta Foradori, one of the leading producers of Teroldego in Trentino as saying "you can't find it anywhere in the world." Well, somebody forgot to tell Poggio al Casone. This estate grows Teroldego and bottles it under their "La Cattura" label with a little bit of Syrah added to it (the bottle I had was 90% Teroldego and 10% Syrah, but their website currently lists the blend as 85/15). I picked my bottle up from the Gypsy Kitchen for about $16. The wine was a deep purple ruby color in the glass and had aromas of black cherry and black plum with a bit of stewed black fruit and a smoky, meaty kind of aroma that I'm guessing may be from the touch of Syrah. On the palate the wine was close to full bodied with medium acidity and soft, well-integrated tannins. There was lush black cherry and plum fruit flavors grounded with some savory earthy notes and a nice long, evolving finish. This wine was the better of the two and really shows what Teroldego is capable of. It's very similar in style to a northern Rhone wine for a fraction of the cost of what many of those bottlings would run you.

So, Teroldego, then. It appears that there may be a sibling relationship between Teroldego and the Pinot family and there is likely a parent/offspring relationship between Teroldego and Lagrein and Marzemino (**UPDATE** Teroldego is definitely one parent of Lagrein, while the other is Schiava Gentile, according to: Cipriani, G. et al. The SSR-based molecular profile of 1005 grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) accessions uncovers new synonymy and parentages, and reveals a large admixture amongst varieties of different geographic origin. 2010. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 121: 1569-1585.). It also turns out that Teroldego is a full sibling (meaning it has the same two parent vines) to a grape called Dureza, which is one of the parent grapes of Syrah. This is interesting in light of a comment from Jim Clendenen of Au Bon Climat winery in California which is quoted in Oz Clarke's Grapes and Wines. Clarke has Clarendon saying that California should have planted Teroldego rather than Merlot and Barbera and, furthermore, it is his belief that if Teroldego were planted on the slopes of Crozes-Hermitage rather than Syrah then the wine there would be greatly improved. Bold talk indeed. Au Bon Climat is primarily a Pinot Noir producer and their terroir isn't necessarily conducive to the Teroldego grape, but I believe that they do have a little Teroldego under vine (according to Eric Asimov of the NYT), though I don't know if they actually bottle and sell any of it (there is no mention on their website). It is possible in California to blend up to 25% of other grape varietals into a single-varietal bottling in California without mentioning it on the label, so its possible that they could use those grapes for that purpose. Some California producers are notorious for adding high color wines like Syrah to their Pinot bottlings for added color and depth so it wouldn't necessarily surprise me, but I'm certainly not going to accuse the winemaker of doing that based on a hunch and some anecdotal evidence.

Teroldego's home is Trentino in the Trentino-Alto Adige region of Italy. We've spent a little time in the Alto Adige visiting with Schiava. Trentino is the southerly portion of this region where the Germanic/Austrian influence isn't quite as pronounced. There are references to Teroldego from Trentino mentioned as far back as the 15th Century. The grape is well suited to warm weather, which may seem a little odd for northern Italy, but they have some areas in the valleys and river basins where the grape can get all the sun and warmth that it needs. It is a thin-skinned variety that produces a deeply colored wine, somehow. There are competing theories about the origin of the name of the grape. I've read that a court in Vienna once called the wine "The Gold of the Tyrol," and somehow that ended up as "Teroldego." I've also read that it has more to do with the wire harnesses, or "tirelles" used to trellis the vine. Matt Kramer, in his Making Sense of Italian Wine contends that that the name derives from the Gernman word teer which means "tar," a flavor which Teroldego can sometimes take on. Take your pick, I guess.

The first wine that I was able to try was the 2005 Teroldego Rotalino (the official DOC name of the region in Trentino where most Teroldego is grown, named for the gravelley river bottom plain called Campo Rotalino near the Adige river) Riserva from Mezzacorona. I was able to pick this up from my friends at Bin Ends for about $20. In the glass, the wine was a dense purple ruby color nearly all the way to the rim. The nose was full of smoky black cherry and black plum with some blackberry and blueberry. On the palate, the wine was close to full bodied with fairly high acid and very little tannin. The grape can be tannic in its youth, but at 6 years out, most of that seemed to be pretty well integrated. There were flavors of black plum, smoky earth, tart cherries and stewed blackberries. The wine was much fruitier and exciting on the nose than on the palate. The finish is kind of abrupt as the fruit really falls off rather than fade away. People have mixed feelings about the age-ability of Teroldego, and after this bottle, I can understand the misgivings.

Talk to people familiar with the grape and they'll tell you that Teroldego grows in Trentino and nowhere else; in fact, Bastianich and Lynch (in their Vino Italiano) quote Elisabetta Foradori, one of the leading producers of Teroldego in Trentino as saying "you can't find it anywhere in the world." Well, somebody forgot to tell Poggio al Casone. This estate grows Teroldego and bottles it under their "La Cattura" label with a little bit of Syrah added to it (the bottle I had was 90% Teroldego and 10% Syrah, but their website currently lists the blend as 85/15). I picked my bottle up from the Gypsy Kitchen for about $16. The wine was a deep purple ruby color in the glass and had aromas of black cherry and black plum with a bit of stewed black fruit and a smoky, meaty kind of aroma that I'm guessing may be from the touch of Syrah. On the palate the wine was close to full bodied with medium acidity and soft, well-integrated tannins. There was lush black cherry and plum fruit flavors grounded with some savory earthy notes and a nice long, evolving finish. This wine was the better of the two and really shows what Teroldego is capable of. It's very similar in style to a northern Rhone wine for a fraction of the cost of what many of those bottlings would run you.

Monday, April 25, 2011

Mauzac - Blanquette de Limoux, France

Welcome, friends and neighbors, to Fringe Wine's 50th post! In honor of reaching this milestone, I've decided to write about an interesting little wine I had recently from southwestern France.

Southwestern France has not, historically, been a hotbed for fine wine growing. The Languedoc (on the Mediterranean coast near the Spanish border) was, and for the most part still is, the most significant contributor to the "wine lake" that exists in France, accounting for approximately one-third of all of the grapes produced in France. Like La Mancha in Spain, though, the tide seems to be turning here as more producers are starting to focus on quality wine production and money from outside investors is starting to come in. Some regions are definitely farther ahead of the curve than others, and one of those regions is Limoux.

Limoux has a very old wine-making tradition. There are records that show that the Romans traded wines from Limoux during their occupation of the region thousands of years ago. Local lore has it that the world's first sparkling wine was made in Limoux in 1531, predating Dom Pérignon by more than a century (we do all know that the Dom Pérignon invention of Champagne is a myth anyway, right?). Much of the wine produced in Limoux today is still sparkling wine, as 3 of the 4 approved AOC categories are dedicated to sparkling wines. There is the obligatory Crémant category that seems to pop up everywhere in France and which is made from mostly Chardonnay grapes with some Chenin Blanc vinified using the traditional Champagne method. There is also the similarly made Blanquette de Limoux which requires that 90% of the blend be from the Mauzac grape with the other 10% being from Chardonnay or Chenin Blanc. And then there's the Blanquette Méthode Ancestrale made from 100% Mauzac.

The méthode ancestrale is different and before we can really talk about how it's different, you need to know a little something about the Mauzac grape. Mauzac is mostly grown in southwestern France (mostly in Gaillac and Limoux), though it is one of the allowed white grapes in Bordeaux. The skin colors for the grapes range from green to black, and while there is a grape called Mauzac Noir, it is not related in any way to Mauzac proper. The most important thing about it, though, is that it is a very late ripener. What this means is that by the time that Mauzac has reached full ripeness in the vineyard, the temperature has already started to drop in the region. It's important to remember that there is a temperature range within which fermentation is possible: too hot and the yeast cells die off; too cold, and they go to sleep and stop doing their work. In the good old days, there wasn't any such thing as temperature control for fermentation vessels so winemakers had to hope for the weather to stay warm long enough so that the fermentation didn't stick. Most grapes are harvested in late summer/early autumn which usually gives enough time before winter sets in for the fermentation to finish its job. Mauzac, though, ripens much later, so by the time it gets to a point where the fermentation is happening, it's well into the autumn. What would traditionally happen is that Mauzac would get stuck in its fermentation when it was about halfway through. The weather would get so cold that the yeast would stop working. The wine was then bottled with the sleeping yeast cells still inside. When spring rolled around, the yeast would wake up and ferment a little more, creating bubbles in the bottle. The wine doesn't ferment all the way dry (it gets up to around 7-8% alcohol), so there's still a bit of sweetness to it. The wine also is not disgorged, so when the yeast cells have given their all and die, they stay in the bottle, which can give méthode ancestrale wines a cloudy appearance.

I was able to find a bottle of Blanquette Méthode Ancestrale from Toad Hollow Vineyards from my friends at Bin Ends for about $12. Those of you who buy a lot of California wine may recognize the Toad Hollow brand and wonder just what is going on here. Toad Hollow, located in northern California, has an agreement with Sieur d'Arques in Limoux and they sell wines made by this estate under the Toad Hollow label. I only even picked up this wine because my wife was pointing out the hideous label on this particular bottle. I had totally missed it, somehow, when combing the racks at Bin Ends, and when I saw what it was, I snatched it up right away. It is not the most aesthetically pleasing thing I've ever seen in my life, but I'm not one to judge a wine by its label. This bottling is also a little unusual in that it also has one of those rubber stoppers on a hinge that fits over the top of the bottle. It is sealed under a traditional mushroom cork, but it does have the rubber stopper for saving some wine for later, I guess.

In the glass, the wine was a pale silvery lemon color and a little fizz. I'm not sure how they did it, but this wine is clear and did not seem to have any debris or sediment floating around in it. The nose had a generous and appetizing aroma with some nice green apple flavors along with a bit of stone fruit and flowers. The wine was light bodied and semi-sweet with nice acidity. It's definitely closer to a frizzante style than a full-blown sparkler. There was candied green apple and sour apple flavors with something a little flowery about it. The flavor characteristic I keep reading about this kind of wine is that they are kind of cidery, and I can see kind of see that. There's definitely a lot of apple flavors in this. The closest comparison I can think to make is to Moscato d'Asti, though this lacks the intense aroma and flowery profile of Moscato. It would be a great wine to serve with brunch or with a apple-centered dessert. I personally had this bottle with some turkey chili and found that it went very well with that as well. It's a simple wine, but that's not always such a bad thing. It's an interesting and unique star in the constellation of worldwide wine that's worth checking out if you can find a bottle.

Southwestern France has not, historically, been a hotbed for fine wine growing. The Languedoc (on the Mediterranean coast near the Spanish border) was, and for the most part still is, the most significant contributor to the "wine lake" that exists in France, accounting for approximately one-third of all of the grapes produced in France. Like La Mancha in Spain, though, the tide seems to be turning here as more producers are starting to focus on quality wine production and money from outside investors is starting to come in. Some regions are definitely farther ahead of the curve than others, and one of those regions is Limoux.

Limoux has a very old wine-making tradition. There are records that show that the Romans traded wines from Limoux during their occupation of the region thousands of years ago. Local lore has it that the world's first sparkling wine was made in Limoux in 1531, predating Dom Pérignon by more than a century (we do all know that the Dom Pérignon invention of Champagne is a myth anyway, right?). Much of the wine produced in Limoux today is still sparkling wine, as 3 of the 4 approved AOC categories are dedicated to sparkling wines. There is the obligatory Crémant category that seems to pop up everywhere in France and which is made from mostly Chardonnay grapes with some Chenin Blanc vinified using the traditional Champagne method. There is also the similarly made Blanquette de Limoux which requires that 90% of the blend be from the Mauzac grape with the other 10% being from Chardonnay or Chenin Blanc. And then there's the Blanquette Méthode Ancestrale made from 100% Mauzac.

The méthode ancestrale is different and before we can really talk about how it's different, you need to know a little something about the Mauzac grape. Mauzac is mostly grown in southwestern France (mostly in Gaillac and Limoux), though it is one of the allowed white grapes in Bordeaux. The skin colors for the grapes range from green to black, and while there is a grape called Mauzac Noir, it is not related in any way to Mauzac proper. The most important thing about it, though, is that it is a very late ripener. What this means is that by the time that Mauzac has reached full ripeness in the vineyard, the temperature has already started to drop in the region. It's important to remember that there is a temperature range within which fermentation is possible: too hot and the yeast cells die off; too cold, and they go to sleep and stop doing their work. In the good old days, there wasn't any such thing as temperature control for fermentation vessels so winemakers had to hope for the weather to stay warm long enough so that the fermentation didn't stick. Most grapes are harvested in late summer/early autumn which usually gives enough time before winter sets in for the fermentation to finish its job. Mauzac, though, ripens much later, so by the time it gets to a point where the fermentation is happening, it's well into the autumn. What would traditionally happen is that Mauzac would get stuck in its fermentation when it was about halfway through. The weather would get so cold that the yeast would stop working. The wine was then bottled with the sleeping yeast cells still inside. When spring rolled around, the yeast would wake up and ferment a little more, creating bubbles in the bottle. The wine doesn't ferment all the way dry (it gets up to around 7-8% alcohol), so there's still a bit of sweetness to it. The wine also is not disgorged, so when the yeast cells have given their all and die, they stay in the bottle, which can give méthode ancestrale wines a cloudy appearance.

I was able to find a bottle of Blanquette Méthode Ancestrale from Toad Hollow Vineyards from my friends at Bin Ends for about $12. Those of you who buy a lot of California wine may recognize the Toad Hollow brand and wonder just what is going on here. Toad Hollow, located in northern California, has an agreement with Sieur d'Arques in Limoux and they sell wines made by this estate under the Toad Hollow label. I only even picked up this wine because my wife was pointing out the hideous label on this particular bottle. I had totally missed it, somehow, when combing the racks at Bin Ends, and when I saw what it was, I snatched it up right away. It is not the most aesthetically pleasing thing I've ever seen in my life, but I'm not one to judge a wine by its label. This bottling is also a little unusual in that it also has one of those rubber stoppers on a hinge that fits over the top of the bottle. It is sealed under a traditional mushroom cork, but it does have the rubber stopper for saving some wine for later, I guess.

In the glass, the wine was a pale silvery lemon color and a little fizz. I'm not sure how they did it, but this wine is clear and did not seem to have any debris or sediment floating around in it. The nose had a generous and appetizing aroma with some nice green apple flavors along with a bit of stone fruit and flowers. The wine was light bodied and semi-sweet with nice acidity. It's definitely closer to a frizzante style than a full-blown sparkler. There was candied green apple and sour apple flavors with something a little flowery about it. The flavor characteristic I keep reading about this kind of wine is that they are kind of cidery, and I can see kind of see that. There's definitely a lot of apple flavors in this. The closest comparison I can think to make is to Moscato d'Asti, though this lacks the intense aroma and flowery profile of Moscato. It would be a great wine to serve with brunch or with a apple-centered dessert. I personally had this bottle with some turkey chili and found that it went very well with that as well. It's a simple wine, but that's not always such a bad thing. It's an interesting and unique star in the constellation of worldwide wine that's worth checking out if you can find a bottle.

Friday, April 22, 2011

Colombard - Bas-Armagnac, France

In the United States, there was a time where it would have been laughable to consider Colombard a fringe grape. Until 1991, it was the most planted white grape in California (where it was known as French Colombard), accounting for over 70,000 acres of plantings at its peak. It formed the base for many jug wines and was allegedly prized for its aromatic profile and its ability to retain acidity in very hot climates (like the Central Valley), but I suspect growers loved it mostly for its massive yields (over 12 tons per acre or over 200 hl/ha). The Chardonnay revolution in California has displaced most Colombard plantings and what is left is nearly all used in jug wine production. The US also has some plantings in Texas and Alabama, of all places, and it is grown successfully in South Africa and Australia as well due to its ability to tolerate very hot conditions.

Colombard's home, though, is France. Everyone's best guess seems to be that Colombard is the result of a crossing of Gouais Blanc and Chenin Blanc. It is thought that it originated in the Charente region of France where it was vinified primarily in order to provide a base for Cognac. That role is being played mostly by Ugni Blanc (Trebbiano) these days, and plantings of Colombard in France have fallen as a result. It is still permitted in Bordeaux and is planted in some of the less prestigious regions there where it is used primarily as a blending grape. It is most widely grown in the Gascony region of Southwestern France where there are some varietal Colombard bottlings available.

Today's wine is from Bas-Armagnac in southwestern France (spanning the Landes and Gers départements in Gascony, for those with an intimate knowledge of French political geography), which is one of the three areas where grapes can be cultivated for Armagnac production. I was able to pick up a bottle of the 2009 Claire de Montesquiou "Espérance" bottling for around $9 from my friends over at Bin Ends. The wine was a pale lemon color in the glass. Even with a heavy chill on it, the nose was generous with grapefruit, green apple, lime and some vegetal asparagus aromas and overall was pretty similar to a Sauvignon Blanc. As the wine warmed up, it opened into more stone fruit and flower aromas, like a nice Viognier. The palate showed the same kind of thing: more green apple and citrus when very cold with more round peach flavors as it warmed up a bit. I personally preferred it with just a slight chill on it, but if you want it to taste a little leaner and sharper, throw it in the fridge overnight and keep it ice cold when serving. There was a nice lingering minerality on the finish which was very refreshing. I imagine this with seafood or other light meat dishes, though it's charming and interesting enough where I wouldn't mind just drinking it on its own. It's a great warm weather wine that I would love to crack open after mowing the lawn. I was very surprised at the quality and relative complexity of this wine given its low price. It seems to be very widely distributed so if you happen to run across it, do yourself a favor and give it a shot.

Colombard's home, though, is France. Everyone's best guess seems to be that Colombard is the result of a crossing of Gouais Blanc and Chenin Blanc. It is thought that it originated in the Charente region of France where it was vinified primarily in order to provide a base for Cognac. That role is being played mostly by Ugni Blanc (Trebbiano) these days, and plantings of Colombard in France have fallen as a result. It is still permitted in Bordeaux and is planted in some of the less prestigious regions there where it is used primarily as a blending grape. It is most widely grown in the Gascony region of Southwestern France where there are some varietal Colombard bottlings available.

Today's wine is from Bas-Armagnac in southwestern France (spanning the Landes and Gers départements in Gascony, for those with an intimate knowledge of French political geography), which is one of the three areas where grapes can be cultivated for Armagnac production. I was able to pick up a bottle of the 2009 Claire de Montesquiou "Espérance" bottling for around $9 from my friends over at Bin Ends. The wine was a pale lemon color in the glass. Even with a heavy chill on it, the nose was generous with grapefruit, green apple, lime and some vegetal asparagus aromas and overall was pretty similar to a Sauvignon Blanc. As the wine warmed up, it opened into more stone fruit and flower aromas, like a nice Viognier. The palate showed the same kind of thing: more green apple and citrus when very cold with more round peach flavors as it warmed up a bit. I personally preferred it with just a slight chill on it, but if you want it to taste a little leaner and sharper, throw it in the fridge overnight and keep it ice cold when serving. There was a nice lingering minerality on the finish which was very refreshing. I imagine this with seafood or other light meat dishes, though it's charming and interesting enough where I wouldn't mind just drinking it on its own. It's a great warm weather wine that I would love to crack open after mowing the lawn. I was very surprised at the quality and relative complexity of this wine given its low price. It seems to be very widely distributed so if you happen to run across it, do yourself a favor and give it a shot.

Monday, April 18, 2011

Freisa d'Asti - Piemonte, Italy

Friends and neighbors, today I have a very unusual treat. Have you ever had a high acid, fiercely tannic wine like Barolo and thought to yourself, "if only this had some bubbles it would be just perfect." If you have, then I may have just found your dream wine. Say hello to our friend Freisa!

Freisa is grown in Piemonte, home of Fringe Wine all stars Grignolino and Brachetto (among many others). It is believed to be native to the region, originating somewhere in the hills between Asti and Turin in the 18th Century. It is related somehow to Nebbiolo, the true star of northwestern Italy, either as one of its parents or one of its offspring. Freisa has two major clones: Freisa Piccolo and Freisa Grossa. Of the two, Freisa Piccolo is the most widely planted. Freisa di Chieri is a subclone of Freisa Piccolo which has its own DOC in the area around Turin. In general, Freisa is a heavy grower, producing heavy vegetation and lots of grapes if not pruned carefully. As a vine, it is somewhat resistant to downy mildew, but can suffer from powdery mildew. The grape is grown almost exclusively in Piemonte with only a few acres in Argentina making up the rest of the world plantings.

It's when we start to talk about styles of wine produced from Freisa that the real fun starts. The wine is produced in a dry, still version, as well as a ripasso style where the Freisa must is fermented on top of Nebbiolo skins, which must make for a seriously tough wine to sip through. The most common presentation of Freisa is in a lightly sparkling form which can be either a little sweet (like Sangue di Giuda) or bone dry (like Lambrusco). "Oh," you might think to yourself, "a little spritz in a red wine can be delightfully refreshing...I've enjoyed many a dry Lambrusco on a summer day and enjoyed them immensely." You're certainly entitled to your opinion, but you should realize going in that Freisa and Lambrusco are two very different grapes and they take to the process with wildly different results. Oz Clarke's take is that it's a "love it or hate it" kind of thing, and that seems to be pretty accurate with some of the world's foremost wine experts. Hugh Johnson considers the wine "immensely appetizing" while Robert Parker considers it "totally repugnant." I find myself somewhere between the two poles, mostly just scratching my head trying to figure out what on earth I just drank.

The bottle I was able to pick up was from Cascina Gilli. It was their Luna di Maggio Freisa d'Asti bottling from the 2007 vintage and it set me back $18. The style of this wine is called "Vivace," which I guess means that its slightly less fizzy than a frizzante style. If they insist there's a difference, I'll believe them, but that's a shade of grey that I can't see. The Luna di Maggio is apparently made from the best quality Freisa grapes at the estate. They get the fizz in there by adding a small amount of sweet wine after the grapes have totally undergone their initial fermentation. The sweet wine starts a secondary fermentation in the bottle that does ferment the sugar to dryness, but which leaves carbon dioxide and a bit of fizzyness in its wake.

In the glass, the wine had an inky, dense purple-black color that was opaque nearly out to the rim. The nose was a little shy with some bitter green vegetable and coffee aromas and not much fruit. The wine is slightly fizzy in the mouth and bone dry with high acid and shockingly high tannins. If you've never had anything like this before, there is no way for you to prepare yourself for the shock of having your mouth stripped out from the tannins in a sparkling wine. You can psych yourself up for it all you want, but you will not be prepared. It will surprise you and you will need a few minutes to collect yourself. Once you've pulled yourself together, there is dark black cherry fruit with some raspberry and espresso notes with a very bitter finish, but good luck getting to and staying with those fruit flavors. I'll be honest: this wine just isn't for me. I'm not saying it's a bad wine, I'm just saying that it doesn't push the right buttons for me as a wine. It has the same kind of structure as a Barolo, but it doesn't have the nice fruit that Barolo has to round out the piercing acidity and rough tannins. The bubbles don't really help as they just seem to accentuate the angularity and awkwardness of the wine in your mouth. Overall, my general sense was of a thin, harsh wine that was just being mean for the sake of meanness. Barolo can beat you up sometimes, but it also gives you something sweet that makes the punishment worthwhile and makes you come back for more; Freisa just seems to want to beat you up and then kick you while you're down.

The common recommendation seems to be that you should serve fizzy Freisa with a slight chill, but it didn't make much difference to me. There may be foods out there that this wine is just made for, but for the life of me I can't think of one. I would love to try a still version or a fizzy version with a some residual sugar in it to see whether its the grape or the style that I can't get over. As always, I never close the book on a wine without trying different producers and different years, but it may take awhile for me to screw up the courage to give this another shot.

Freisa is grown in Piemonte, home of Fringe Wine all stars Grignolino and Brachetto (among many others). It is believed to be native to the region, originating somewhere in the hills between Asti and Turin in the 18th Century. It is related somehow to Nebbiolo, the true star of northwestern Italy, either as one of its parents or one of its offspring. Freisa has two major clones: Freisa Piccolo and Freisa Grossa. Of the two, Freisa Piccolo is the most widely planted. Freisa di Chieri is a subclone of Freisa Piccolo which has its own DOC in the area around Turin. In general, Freisa is a heavy grower, producing heavy vegetation and lots of grapes if not pruned carefully. As a vine, it is somewhat resistant to downy mildew, but can suffer from powdery mildew. The grape is grown almost exclusively in Piemonte with only a few acres in Argentina making up the rest of the world plantings.

It's when we start to talk about styles of wine produced from Freisa that the real fun starts. The wine is produced in a dry, still version, as well as a ripasso style where the Freisa must is fermented on top of Nebbiolo skins, which must make for a seriously tough wine to sip through. The most common presentation of Freisa is in a lightly sparkling form which can be either a little sweet (like Sangue di Giuda) or bone dry (like Lambrusco). "Oh," you might think to yourself, "a little spritz in a red wine can be delightfully refreshing...I've enjoyed many a dry Lambrusco on a summer day and enjoyed them immensely." You're certainly entitled to your opinion, but you should realize going in that Freisa and Lambrusco are two very different grapes and they take to the process with wildly different results. Oz Clarke's take is that it's a "love it or hate it" kind of thing, and that seems to be pretty accurate with some of the world's foremost wine experts. Hugh Johnson considers the wine "immensely appetizing" while Robert Parker considers it "totally repugnant." I find myself somewhere between the two poles, mostly just scratching my head trying to figure out what on earth I just drank.

The bottle I was able to pick up was from Cascina Gilli. It was their Luna di Maggio Freisa d'Asti bottling from the 2007 vintage and it set me back $18. The style of this wine is called "Vivace," which I guess means that its slightly less fizzy than a frizzante style. If they insist there's a difference, I'll believe them, but that's a shade of grey that I can't see. The Luna di Maggio is apparently made from the best quality Freisa grapes at the estate. They get the fizz in there by adding a small amount of sweet wine after the grapes have totally undergone their initial fermentation. The sweet wine starts a secondary fermentation in the bottle that does ferment the sugar to dryness, but which leaves carbon dioxide and a bit of fizzyness in its wake.

In the glass, the wine had an inky, dense purple-black color that was opaque nearly out to the rim. The nose was a little shy with some bitter green vegetable and coffee aromas and not much fruit. The wine is slightly fizzy in the mouth and bone dry with high acid and shockingly high tannins. If you've never had anything like this before, there is no way for you to prepare yourself for the shock of having your mouth stripped out from the tannins in a sparkling wine. You can psych yourself up for it all you want, but you will not be prepared. It will surprise you and you will need a few minutes to collect yourself. Once you've pulled yourself together, there is dark black cherry fruit with some raspberry and espresso notes with a very bitter finish, but good luck getting to and staying with those fruit flavors. I'll be honest: this wine just isn't for me. I'm not saying it's a bad wine, I'm just saying that it doesn't push the right buttons for me as a wine. It has the same kind of structure as a Barolo, but it doesn't have the nice fruit that Barolo has to round out the piercing acidity and rough tannins. The bubbles don't really help as they just seem to accentuate the angularity and awkwardness of the wine in your mouth. Overall, my general sense was of a thin, harsh wine that was just being mean for the sake of meanness. Barolo can beat you up sometimes, but it also gives you something sweet that makes the punishment worthwhile and makes you come back for more; Freisa just seems to want to beat you up and then kick you while you're down.

The common recommendation seems to be that you should serve fizzy Freisa with a slight chill, but it didn't make much difference to me. There may be foods out there that this wine is just made for, but for the life of me I can't think of one. I would love to try a still version or a fizzy version with a some residual sugar in it to see whether its the grape or the style that I can't get over. As always, I never close the book on a wine without trying different producers and different years, but it may take awhile for me to screw up the courage to give this another shot.

Friday, April 15, 2011

Mencía - Bierzo and Monterrei, Spain

Mencía appears to be a grape on the rise. Over the past few months, I've noticed quite a few of the wine shops whose email lists I'm on start to offer more and more wines made with Mencía from northwest Spain. I've also started to notice that most shops that I visit these days have at least one wine made from Mencía and some shops have three or four different bottles to choose from. The main reason, I'd guess, is the price. These wines are generally very good values and tend to really over-perform for what you'll find yourself paying for them. It hasn't taken over the world just yet, though, so here's my take on Mencía.

Mencía, like our friend Godello, finds it home in northwestern Spain. This area of Spain is much different, climatically, from the rest of the country, as it tends to be a little cooler and receives much more rain. The main region for Mencía is Bierzo, which is just north of Valdeorras. The rainfall isn't quite as heavy and the temperature is generally warmer in Bierzo than in some areas of northwest Spain. The region is hilly, as you can see in the picture at right, and the vines tend to be planted on very steep hillsides at altitudes as high as 2,300 feet. For many years, Bierzo was a coal mining center for Spain but most of those mines were shut down in the 1980's. Facing a serious economic crisis, the region transformed itself into a tourist center and invested more heavily in developing agriculture, especially viticulture. It has only started to emerge on the worldwide quality wine scene in the last 20-30 years, but it has come on strong and fast.

For many years Mencía was thought to be either identical or closely related to Cabernet Franc. Noted Spanish wine expert Julian Jeffs, as recently as 1999, commented that Mencía was "generally equated with Cabernet Franc." Recent DNA evidence has shown that the two grapes are not related, though, they do share some similarities in their aroma and flavor profiles. DNA testing has revealed that Mencía is identical to a Portuguese grape called Jaen and winemakers in Spain and Portugal are permitted to use either name on their bottles. The grape is grown fairly widely in northwestern Spain, though the primary wine markets in the this part of the country are for white wines. In addition to Bierzo, one of the wines I sampled was from Monterrei (southwest of Bierzo), an area which Doug Frost in his 2008 Wines from Spain: Far From Ordinary Wine Guide, refers to as a DO with "little more to offer than promise at the moment" and which "[isn't] a factor in the marketplace at the moment." As a testament to this grape and this region's sudden rise, wines from some of these other northwestern regions are starting to show up in greater numbers, only three years after that was written.

The first wine I that I tried was the 2008 Luna Beberide from Bierzo. I picked this up at vinodivino in Brookline for about $17. The wine was fermented in stainless steel vats and is unfiltered. In the glass it was a deep ruby color with a light violet rim. The had a bit of a stewed smell, almost like stewed tomatoes, and a little bit of an earthy graphite note. There wasn't much going on with the nose here. In the mouth, though, the wine was fully bodied with medium acid and soft tannins. There were spicy cherry and and fleshy black plum flavors with some blackberry and a smoky kind of minerality to it. The wine itself wasn't sweet, but it had that sensation that I associate with the descriptor "sweet tannins" that always throws me a little bit. Everything else here was nicely balanced, but that sensation kept me from really getting excited about this. I was a little concerned as well because most of the descriptions that I had read about Mencía caused me to expect a lighter colored wine with more red berry fruits in it. For many years, apparently, this was the style produced in Bierzo because growers were not utilizing the excellent slopes in the region for vines and were planting them on the fertile alluvial plains in the region. This lead to overproduction and thin juice. Bierzo was evolving so rapidly that many books were really behind the times when it came to the current state of affairs in this region. I held off on writing about Mencía until I could get another bottle to see how atypical my experience really was.

The second bottle that I picked up was the 2009 Benaza Mencía from Monterrei. I grabbed this for about $13 from Curtis Liquors in Weymouth. This wine was also a nice purple ruby in the glass. The nose had waxy cherry and stewed strawberry fruit with a raspy kind of dried herb edge to it. In the mouth, the wine was medium bodied with medium acidity and little tannin. The palate followed the nose pretty closely with red cherry and stewed strawberry fruits with some raspberry. It was mostly a nice, juicy red-fruit driven wine with a touch of smoke on the finish. It's not the kind of thing that's going to blow you away, but it was a very nice, friendly little red wine. It was pretty similar to Loire Valley Cabernet Franc in its flavor profile and structure, which is just fine by me. This experience was much closer to what I was expecting from Mencía, though it still showed more character and extraction than many of the books I had read led me to believe was possible from this grape. The bottom line is that northwest Spain is making some very good red wines from the Mencía grape and the price is right for these bottles right now.

For many years Mencía was thought to be either identical or closely related to Cabernet Franc. Noted Spanish wine expert Julian Jeffs, as recently as 1999, commented that Mencía was "generally equated with Cabernet Franc." Recent DNA evidence has shown that the two grapes are not related, though, they do share some similarities in their aroma and flavor profiles. DNA testing has revealed that Mencía is identical to a Portuguese grape called Jaen and winemakers in Spain and Portugal are permitted to use either name on their bottles. The grape is grown fairly widely in northwestern Spain, though the primary wine markets in the this part of the country are for white wines. In addition to Bierzo, one of the wines I sampled was from Monterrei (southwest of Bierzo), an area which Doug Frost in his 2008 Wines from Spain: Far From Ordinary Wine Guide, refers to as a DO with "little more to offer than promise at the moment" and which "[isn't] a factor in the marketplace at the moment." As a testament to this grape and this region's sudden rise, wines from some of these other northwestern regions are starting to show up in greater numbers, only three years after that was written.

The first wine I that I tried was the 2008 Luna Beberide from Bierzo. I picked this up at vinodivino in Brookline for about $17. The wine was fermented in stainless steel vats and is unfiltered. In the glass it was a deep ruby color with a light violet rim. The had a bit of a stewed smell, almost like stewed tomatoes, and a little bit of an earthy graphite note. There wasn't much going on with the nose here. In the mouth, though, the wine was fully bodied with medium acid and soft tannins. There were spicy cherry and and fleshy black plum flavors with some blackberry and a smoky kind of minerality to it. The wine itself wasn't sweet, but it had that sensation that I associate with the descriptor "sweet tannins" that always throws me a little bit. Everything else here was nicely balanced, but that sensation kept me from really getting excited about this. I was a little concerned as well because most of the descriptions that I had read about Mencía caused me to expect a lighter colored wine with more red berry fruits in it. For many years, apparently, this was the style produced in Bierzo because growers were not utilizing the excellent slopes in the region for vines and were planting them on the fertile alluvial plains in the region. This lead to overproduction and thin juice. Bierzo was evolving so rapidly that many books were really behind the times when it came to the current state of affairs in this region. I held off on writing about Mencía until I could get another bottle to see how atypical my experience really was.

The second bottle that I picked up was the 2009 Benaza Mencía from Monterrei. I grabbed this for about $13 from Curtis Liquors in Weymouth. This wine was also a nice purple ruby in the glass. The nose had waxy cherry and stewed strawberry fruit with a raspy kind of dried herb edge to it. In the mouth, the wine was medium bodied with medium acidity and little tannin. The palate followed the nose pretty closely with red cherry and stewed strawberry fruits with some raspberry. It was mostly a nice, juicy red-fruit driven wine with a touch of smoke on the finish. It's not the kind of thing that's going to blow you away, but it was a very nice, friendly little red wine. It was pretty similar to Loire Valley Cabernet Franc in its flavor profile and structure, which is just fine by me. This experience was much closer to what I was expecting from Mencía, though it still showed more character and extraction than many of the books I had read led me to believe was possible from this grape. The bottom line is that northwest Spain is making some very good red wines from the Mencía grape and the price is right for these bottles right now.

Monday, April 11, 2011

Moschofilero - Peloponnesos, Greece

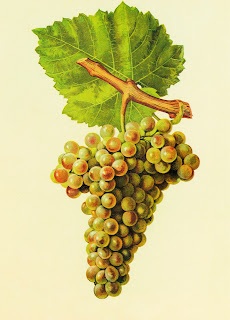

Looking at the grapes over on the left, if you had to hazard a guess, what style of wine would think they would produce? My first thought would probably be a light red wine like Schiava or Pinot Noir, and I'd be wrong. Those are Moschofilero grapes from Greece and, like their pink-skinned Greek counterpart Roditis, they are used to produced a white wine.

Much of the Moschofilero grown in Greece is grown in the region of Peloponnesos. We've briefly visiting Peloponnesos before: both Agiorghitiko and Roditis are produced in this region. Roditis is grown in Patras, at the far north of Peloponnesos while Agiorgitiko is grown in Nemea in the northeastern corner. Moschofilero is grown all over Peloponnesos and on many of the smaller islands, but the best of it is grown in Mantinia, located just south of Patras and just southwest of Nemea.

One might think, based on the name of the grape, that Moschofilero may have some kind of relation to one of the many Muscat varietals, but it doesn't. The "moscho" part of the grape name is derived from the world "moschato," which means aromatic, which both Moschofilero and Muscat certainly are. It is also not related to Gewurztraminer though it certainly can resemble it. So now we know what Moschofilero isn't, how about we talk about what it is? It is a genetically unstable grape, meaning there is a lot of clonal variation. It's kind of like how Torrontés is actually three different grapes; there are similarly three different clones of Moschofilero that make up most of the plantings in Greece: Asprofilero, Xanthrofilero and Mavrofilero (which itself has two different sub-clones with wildly different sugar contents), all of which have different skin colors (aspro = white, xanthro = blonde and mavro = black), leaf shapes, bunch shapes and growing habits. Additionally, the variants have different pick times and different acid and sugar levels. Since all of the clonal variants are allowed to fly under the catch-all "Moschofilero" banner, chances are that what's in the bottle that you find is probably a blend of several different clones.

There are two bottles under consideration here today. The first is the 2006 Nasiakos Moschofilero from the Mantinia region. I picked this up for around $16 (I didn't get a picture of the label and can't find anything online that looks similar). The wine had a golden color in the glass and I immediately began to wonder if this was over the hill. The nose was very reticent with just little bit of honeysuckle flower to it. This was my first Moschofilero, so I wasn't sure if something was amiss or not, because everything I had read about this wine was extolling its wonderful perfume and this wine was just not there aromatically. I pressed on, though, and found the wine pretty full-bodied in the glass with high acidity and nice white peach, honeysuckle and lemon curd flavors. There was definitely a creamy citrusy thing going on here. It was a nicely balanced wine with the acid really holding the surprisingly full body together. This wine was certainly not dead in the bottle, but it was disappointing to see the aromatics fade so quickly. I made a note to buy a more recent vintage and after searching for awhile, I finally found one.

I picked up a bottle of the 2009 Skouras Moschofilero from my friends at Bin Ends for about $14.50. The color was a much lighter straw color in the glass. The nose was explosively fragrant with lemon/lime citrus, green apple, and orange blossom. It was very reminiscent of a dry Muscat or a Gewurztraminer and was much more like what I had been expecting from this grape. This wine was more light/med bodied with very high acidity (bracingly acidic is the phrase in my notes). The flavors were very lemony with some green apple, white peach, apricot and honeysuckle in there as well. It finished with that slightly grapey flavor that muscat is known for, but the finish evolves into a nice steely crispness right at the end. The wine continued to open up and evolve as I drank through the bottle. The flavor profile was somewhere between an Rkatsiteli and a Muscat for me with lots of flowery citrus. This wine was superior to the older bottling and I would recommend that you drink this wine young to fully enjoy its lovely perfume. I think it is a very versatile food wine that would also be a perfect aperitif that would be guaranteed to get some conversations started at a party.

Wednesday, April 6, 2011

Chasselas - Switzerland

Chasselas is a grape with many names. The Vitis International Variety Catalog lists 216 different names for this grape. Those who are interested can feel free to peruse the list over on the VIVC database. Generally, when a grape has that many names, it means that it's grown in a lot of different places, which is true: there are significant plantings in Germany and Austria and lesser plantings in France, Eastern Europe, northern Italy, Australia and Chile (what is grown in California as Golden Chasselas is probably really Palomino). It is a star grape, though, in only one place: Switzerland.

When one stops and reflects on the great, traditional wine regions of the world, Switzerland is not likely to cross many people's minds. Viticulture is not a new phenomenon here, though. Grape growing has a history in Switzerland going back at least to Roman times, though it is possible that its roots go back another thousand years. Geographically, Switzerland is perhaps most associated with the high mountains of the Swiss Alps, but the Alps only constitute about 60% of the total land area of the country. There is a large plateau just north of the Alps where most of the population of the country is located and which provides nearly all of the arable land for the country. There are some grapes grown in some of the more mountainous areas and some grown in the northeastern part of the country, but the most important regions are located in the western part of the country around Lake Geneva near the French border.

Somewhat surprisingly, given the mountainous terrain and northerly latitude, red wine production accounts for almost 60% of Swiss output with Pinot Noir (30% of vineyard acreage) and Gamay (10% of vineyard acreage) leading the way. The other 40% is white wine and the overwhelming majority of white wine is produced from the Chasselas grape. Chasselas covers about 27% of the vineyard area of Switzerland with the next closest white varietal being Müller-Thurgau at 3.3%. For while, it was thought that Chasselas originated in Turkey or possibly Egypt and was the oldest known grape variety in the world, which may account for the overwhelming number of names it has. More recent research, though, seems to indicate that the grape is native to Switzerland. The Swiss make the most wine from Chasselas, but other countries in eastern Europe actually have more land devoted to cultivating the grape, but it is primarily grown as a table grape in those areas.

I was able to pick up a bottle of 2009 Dubaril Chasselas Vin de Pays from my friends at Bin Ends for about $13. There is an appellation system in Switzerland that is very similar to the French AOC system. Because this wine is labeled Vin de Pays, I don't have any more specific geographical reference for where it was produced than the name of the country itself. I will say, though, that I've had Chasselas at various tastings from the Valais and Vaud regions of Switzerland, which are perhaps the best known wine producing regions in that country and that my impressions of the grape have been similar every time I have tried it.

In the glass, the wine was a pale, silvery straw color. The nose was moderately open, but very one dimensional smelling of pears and little else. On the palate, the wine was medium bodied with low acidity. I guess the diplomatic thing to say is that Swiss neutrality does not stop with their politics. The wine has a chalky kind of minerality to it with a little bit of apple peel and ripe pear fruit, but overall, there's just not much there. Every time I taste a Chasselas, I get this overwhelming chalky taste that is a bit off-putting for me. Plus, the wines are generally low in both acid and fruit so there's not much else in the wine to off-set that chalky sensation. I keep waiting for a Chasselas-based wine to really grab me, but it just hasn't happened yet. I'm not so chauvinistic about it that I'll write the whole grape and region off, but if anyone has any recommendations on the Chasselas front, please let me know as I'd love to have my mind changed about it. I've heard that these are great fondue wines, and I guess that's as good a use as any for them.

When one stops and reflects on the great, traditional wine regions of the world, Switzerland is not likely to cross many people's minds. Viticulture is not a new phenomenon here, though. Grape growing has a history in Switzerland going back at least to Roman times, though it is possible that its roots go back another thousand years. Geographically, Switzerland is perhaps most associated with the high mountains of the Swiss Alps, but the Alps only constitute about 60% of the total land area of the country. There is a large plateau just north of the Alps where most of the population of the country is located and which provides nearly all of the arable land for the country. There are some grapes grown in some of the more mountainous areas and some grown in the northeastern part of the country, but the most important regions are located in the western part of the country around Lake Geneva near the French border.

Somewhat surprisingly, given the mountainous terrain and northerly latitude, red wine production accounts for almost 60% of Swiss output with Pinot Noir (30% of vineyard acreage) and Gamay (10% of vineyard acreage) leading the way. The other 40% is white wine and the overwhelming majority of white wine is produced from the Chasselas grape. Chasselas covers about 27% of the vineyard area of Switzerland with the next closest white varietal being Müller-Thurgau at 3.3%. For while, it was thought that Chasselas originated in Turkey or possibly Egypt and was the oldest known grape variety in the world, which may account for the overwhelming number of names it has. More recent research, though, seems to indicate that the grape is native to Switzerland. The Swiss make the most wine from Chasselas, but other countries in eastern Europe actually have more land devoted to cultivating the grape, but it is primarily grown as a table grape in those areas.

I was able to pick up a bottle of 2009 Dubaril Chasselas Vin de Pays from my friends at Bin Ends for about $13. There is an appellation system in Switzerland that is very similar to the French AOC system. Because this wine is labeled Vin de Pays, I don't have any more specific geographical reference for where it was produced than the name of the country itself. I will say, though, that I've had Chasselas at various tastings from the Valais and Vaud regions of Switzerland, which are perhaps the best known wine producing regions in that country and that my impressions of the grape have been similar every time I have tried it.

In the glass, the wine was a pale, silvery straw color. The nose was moderately open, but very one dimensional smelling of pears and little else. On the palate, the wine was medium bodied with low acidity. I guess the diplomatic thing to say is that Swiss neutrality does not stop with their politics. The wine has a chalky kind of minerality to it with a little bit of apple peel and ripe pear fruit, but overall, there's just not much there. Every time I taste a Chasselas, I get this overwhelming chalky taste that is a bit off-putting for me. Plus, the wines are generally low in both acid and fruit so there's not much else in the wine to off-set that chalky sensation. I keep waiting for a Chasselas-based wine to really grab me, but it just hasn't happened yet. I'm not so chauvinistic about it that I'll write the whole grape and region off, but if anyone has any recommendations on the Chasselas front, please let me know as I'd love to have my mind changed about it. I've heard that these are great fondue wines, and I guess that's as good a use as any for them.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)