As mentioned above, Inzolia/Ansonica are first mentioned definitively in the literature around the 16th or 17th centuries. I say definitively because the ancient Roman writer Pliny the Elder mentions a grape called Irziola in his Naturalis Historia, which some have taken to be the first mention of Inzolia in print, but aside from their similar sounds, there is no evidence that indicates that Pliny was talking about the grape we know as Inzolia today. In Sicily, Inzolia has historically been found mainly on the western end of the island where it is has been valued as an ingredient, along with Grillo, in high-end Marsala production. As the production of high-end Marsala has fallen, Inzolia has given way to Catarratto, which is more widely used for low-end Marsala production. Inzolia is still relatively widely planted, though, as current Sicilian acreage stands at around 19,000 acres. As table wine production has taken off in Sicily over the past few decades, more and more of the existing Inzolia plantings have been used for that purpose as well.

In Tuscany, the grape is known as Ansonica and is planted mainly along the coast and on some of the nearby islands of the Tuscan archipelago. The most famous of these seven islands is Elba, where Napoleon was banished in 1814, and while Ansonica is grown there, the island we're most concerned with is called Giglio. Giglio is a small (about 1.36 square miles), mountainous island made primarily of granite and located about 10 miles from the Tuscan shore. It has been inhabited since the Stone Age and has been ruled over by the Etruscans, Greeks, Romans and Florentines among others. At various times throughout history, the island has been completely abandoned as invading forces deported the native population, but it has always been resettled eventually. Grapes have been grown on this island since at least the 6th Century BC, and today, Ansonica is the mostly widely planted grape there.

Despite their geographical distance, ampelographers have long suspected that Inzolia and Ansonica were the same grape and the Italian authorities have recognized them as the same for many years. In 1999, the first DNA evidence started coming in which validated this particular hypothesis. An Italian team used AFLP markers, which are a little bit different from the microsatellite markers primarily used today, to show that the Ansonica from Giglio was most closely related to Ansonica from the Tuscan mainlaind, Inzolia from Sicily, Roditis from Greece, Airén from Spain and Clairette from France. While these results are interesting, we do have to take them with a grain of salt. AFLP analysis is looking at DNA sites throughout a sample's genome, which means that it can be more precise than microsatellite analysis, but that precision isn't necessarily a good thing. If you're looking for a murderer, then you want to be as precise as possible, but when you're dealing with families of plants that are subject to genetic mutation over time, that precision can indicate differences in two plants that you would otherwise consider to be identical.* Clonal variants can show up in AFLP analysis as different varieties, as can geographically disparate populations that shared a common ancestor hundreds of years ago, but which have been evolving separately from one another ever since. This is the case with Inzolia and Ansonica, and this AFLP analysis was able to show that there were differences not only between Tuscan Ansonica and Sicilian Inzolia, but also between Ansonica from Giglio and Ansonica from Tuscany. The two Ansonicas were closer to one another than to Inzolia from Sicily and the Tuscan Ansonica was closer to the Sicilian Inzolia than the Giglio Ansonica was, which would indicate that the grape likely came from Sicily to Tuscany and then to Giglio.

I mentioned above that this study also found similarities between Inzolia/Ansonica and Roditis, Airén and Clairette, and this probably needs a bit of explanation as well. Many genetic studies compare large groups of grapes from specific geographic regions in order to see how similar they are to one another genetically. The theory is that grapes from a certain region have likely been together a very long time and are probably distantly related to one another in ways that are too complicated to tease out with pedigree analysis. When testing a large pool of grapes, the scientists look to see which grapes have the most DNA in common with one another and then hypothesize that these grapes are then more closely related to one another than to the other grapes in the study. The main problem in interpreting the results is that you are limited by the number and the variety of grapes in a study. The results are really only telling you that these grapes are more like each other than the other grapes in the study, which can be problematic if you've chosen your samples poorly. Imagine a study like this done with human beings where you're Italian and your family has lived in a small village for hundreds of years. The researchers select you and a handful of people from your town and compare them with another group from the mountains of Tibet. The study should show that you are more closely related to the people from your village than the villagers of Tibet. Now imagine that the study took you, one person from the village in Tibet, and a pack of chimpanzees. Suddenly you and the Tibetan villager look a lot more closely related.

The point is that these relatedness studies can be useful, but they can also be misleading. The group above sampled a very high number of Greek grapes along with a handful of grapes from a whole bunch of different regions all over the world. They tested very few Sicilian or Tuscan varieties, which one would expect to be more closely related, and so the results may be a little skewed. They interpreted their results as showing that Inzolia likely came from Greece, due to its relatedness to Roditis, into Sicily before moving to Tuscany and then to Giglio. In Wine Grapes, Vouillamoz points to a 2010 study (citation 1) where another Italian team analyzed 82 different Sicilian grapes to see how closely they were related as refutation of the study above. They found that Inzolia was mostly closely related to a few other varieties with Inzolia in the name (but which are separate varieties) such as Inzolia Imperiale and Inzolia Nera (which is not a red-berried mutation of Inzolia at all, but rather a separate variety). Further, this group also had similarities with Coda di Volpe, Grecanico, Frappato, Carricante and Nerello Mascalese among others. Vouillamoz claims that the relatedness of Inzolia to these other Sicilian grapes indicates that it is likely from Sicily and not from Greece. Since this particular study did not include any Greek grape varieties, it seems difficult to compare the results from the different studies and come to that kind of conclusion. Both studies do seem to indicate that Inzolia came from Sicily to Tuscany, but whether it is native to Sicily or whether its ancestors or Greek seems to still be an open question.

I was able to try two different wines, one from Sicily and one from Giglio, made from the Inzolia/Ansonica grape. The first was the 2009 Ansonaco from Familia Carfagna, which I picked up for around $50 from my friends at the Wine Bottega (though I have recently seen it available at Curtis Liquors as well). In the glass the wine was a medium bronze gold color. The nose was intense with aromas of ripe red apples, toasted nuts, apple cider, poached pear, brown sugar, dried apple and abundant autumn spice. On the palate the wine was medium bodied with fairly acidity. There were flavors of dried apricot, red apple, apple cider, toasted almonds, autumn spice and dried leaves. I would have sworn that this wine saw some skin contact, but this website seems to indicate no maceration. I thought this was a really gorgeous wine that was an absolute pleasure to drink. It should be drunk at cellar or room temperature, as the cold really blunts the aromas and flavors. It is a bit pricey but I thought it was worth every penny. You probably could pair this with some food, but I really just enjoyed it on its own.

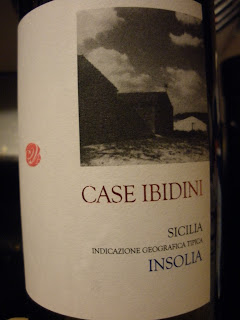

The second wine that I tried was the 2010 Case Ibidni Inzolia from Sicily, which I picked up from my friends at the Wine Bottega for around $12. In the glass the wine was a medium lemon yellow color. The nose was moderately intense with aromas of ripe white pear, green melon, ripe apple and something vaguely tropical. On the palate the wine was on the lighter side of medium with medium acidity. There were flavors of ripe, round white pear and red apple along with a touch of mild pineapple and banana. Inzolia does have a tendency to get flabby if not picked early enough, and I think that these grapes maybe hung on the vine a little too long. It had some of those flat fruit-cocktail kinds of flavors going on and really wasn't my thing.

Reader and frequent commenter WineKnurd was able to try a more recent vintage (2011) of this wine which he picked up from his friends at Wine Authorities in Durham, North Carolina. His tasting note reads:

"100% Insolia from Sicily, 12.5% abv with a slight spritz in the glass on first pour. Classic Italian white wine nose full of wet stone and minerals backed with notes of fresh cut granny smith apple and some hints of cantaloupe rind. The palate was lighter and less intense than I was expecting based on the nose and the wine in general had lower acidity than what I was expecting for an Italian white. Up front there are flavors of sour apple and melon rind but somewhere along the mid-palate it thins out and finishes weak. My guess is that this needs to be consumed as fresh as possible in Sicily, not a year behind in the USA. At $12.99 it doesn't break the bank but this is money better spent elsewhere."

CITATION

1) Carimi, F, Mercati, F, Abbate, L, & Sunseri, F. 2010. Microsatellite analyses for evaluation of genetic diversity among Sicilian grapevine cultivars. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 57(5): pp 703-719.

*It really seems to be taken for granted that Inzolia and Ansonica are genetically identical, but I actually was not able to find any studies that specifically prove the synonymy. I checked the microsatellite profile data in the VIVC with the data given for Inzolia in Citation 1 and found that the adjusted values matched at all six sites, so that's good enough for me.

No comments:

Post a Comment