Let's talk about the Blauer Portugieser grape. Of the two words in the grape's name, Blauer may seem like the one that needs the most explanation. Not true. Blauer simply means "blue" and is a fairly common prefix for German/Austrian grape names (think Blaufränkish or Blauburgunder). Of course, that may immediately lead to another question: why does a grape called "Portugieser" need a Germanic prefix? Well, Austria and Germany are the most prolific growers of Portugieser, as it is the third most planted red variety in each of those two countries (it occupies between 4,000 and 5,000 hectares in each). The vine is also widely spread throughout Eastern Europe and is grown in Croatia, the Czech Republic, Romania, Slovenia, and Hungary, where it is one of the permitted grapes in the Bull's Blood blend. It was even once widely grown in southwestern France, where it was known as Oporto or Portugais Bleu. So where does it rank in Portuguese production? Well, it doesn't.

As far as I can tell, Portugieser isn't actually grown in Portugal at all. In fact, depending on what sources you use, Portugieser may not have any connection to Portugal whatsoever. The Austrian Wine website maintains that the grape is native to Portugal and was taken to Austria by the Baron von Fries in 1770. Most other sources, though, indicate that the grape is native to Austria with no apparent or proven link either to Portugal or to any other Portuguese grape. The von Fries origin story must be persistent, though, as most of the synonyms for Portugieser incorporate some reference to Portugal: Kékoporto in Hungary, Modrý Portugal in the Czech Republic, Portugaljka in Croatia, etc. (those who are terribly interested can peruse the full list of synonyms here). I suppose it's possible that wines made from the Portugieser grape reminded the drinkers of wines from Portugal, but that seems unlikely given the grape's reputation for producing pale, light bodied red wines, a far cry from the powerhouse Ports that were likely in circulation in the 18th and 19th Centuries.

Whatever the true origin of the name is, the grape is now widely known as Portugieser and is relatively widely planted, though little of it gets exported. Mostly this is because the wines made from the grape have a pretty lousy reputation. The Oxford Companion to Wine writes that Portugieser is a "black grape variety common in both senses of that word in Austria and Germany" which "can taste disconcertingly inconsequential to non-natives." They further write "such wines are rarely exported, with good reason, and are only rarely worthy of detailed study." So why does the grape take up so much real estate in these countries?

Well, the main reason is that Blauer Portugieser is really easy to grow. It is resistant to a wide range of vine diseases, most specifically coulure, or poor fruit set (when the berries are very young, many of them fall off, which is called coulure). Because of its resistance to this particular affliction, Portugieser is an explosive yielder, sometimes producing as much as 120 hl/ha of juice, or around 7 tons of fruit per acre. As you might expect, if the vine is allowed to produce to its full potential, the resulting wines are dilute and the grape's naturally low acidity is stretched even thinner. There are some producers who are trying to produce fine wines from this unappreciated grape by restricting yields, using old vines and barrel-maturing their wine.

To be honest, I'm not at all sure if the maker of the bottle I bought is one of these producers or not. I tried to go to the producer's website, and, after fighting off the pop-up ads for getting a green card, was unable to understand anything on the site, since the English translation button doesn't seem to work (I took Latin in school so these Germanic languages are pretty opaque to me). So, we'll just have to go by what's in the bottle. The wine I was able to find was from Pretterebner and it was from the 2004 vintage. I picked it up for about $13. In the glass, the wine was a medium ruby color with a fruity, grape juice kind of nose. There were also some aromas of plum and red cherry. On the palate, the wine was medium bodied with no tannins and acidity on the lower side of medium. It tasted a bit like watered down grape juice with some cherry and raspberry fruit. As the wine sat in my glass, it started to pick up a kind of rubbery aroma and taste that reminded me of when I was a kid and on really hot days, we would drink water from a garden hose. The smell and taste of the water that had been sitting in the hose in the sun is kind of what this started to taste like. Unfortunately, it didn't get a whole lot better as the rubbery smell and taste started to taste a little burnt. It really started to remind me of some really lousy Pinotage wines that I've had. My sum-it-up line in my notes reads "this was nice for the first 10 minutes it was open...then it tasted like an old tire." This is certainly not my new favorite wine, but as with so many others on this site, I'm not willing to write it off wholesale because of one bottle. I'll give it another shot, but I'd pass on this particular bottling unless you're really into drinking what a car accident smells like.

Tuesday, May 31, 2011

Wednesday, May 25, 2011

Trepat - Penedès, Catalonia, Spain

Let's talk about Cava for a little bit. I know, I know, Cava is everywhere and hardly qualifies for a site like this, but hear me out. Yes, a lot of Cava is made (about 31 million gallons per year or about 1/3 of the total output of Champagne), and yes, a lot of it is your standard, run of the mill stuff made from one, some, or all of the three primary white grapes: Macabeo (known as Viura in Rioja), Xarel-lo and Parellado. Your typical bottle of Cava is probably made from a blend of these grapes with Macabeo generally accounting for about half of the final blend. There are other grapes that are permitted in the Cava blend, though. The ubiquitous Chardonnay has been permitted for the last 25 years or so, and Malvasia can also be found in some Cava blends.

But not all Cava is made from white grapes. There are rosado Cavas available as well and the grapes permitted in those wines are Garnacha (Grenache), Monsatrell (Mourvedre), Pinot Noir and Trepat. Three of those grapes should be pretty recognizable to the average, informed wine consumer, as they have homes elsewhere in the world where they get to be shining stars, but Trepat? What the heck is Trepat?

My first line of attack in most of my research is the Oxford Companion to Wine, which is not particularly helpful when it comes to Trepat. The book's entry reads in full: "indigenous red wine grape of north east Spain, particularly in Conca de Barberá and Costers del Segre. About 1,500 ha/3,700 acres are grown, used mainly for light rosés, but it has shown some intriguing potential for fine reds." A little extra digging shows that Trepat is picky about the soils it thrives in (it's not a fan of calcium-rich soils), though it does appear to be pretty resistant to most fungal diseases. It buds early and is thus susceptible to frost damage, which is more of a problem in this region at some of the higher altitudes, but Trepat is generally planted on lower-altitude sites. There are a few sources that say that there is as little as1,000 ha of Trepat planted, and I'm not aware of any plantings outside of Spain. The overwhelming majority of the grapes grown are used in the production of rosado Cava, though there are a few producers who do make a still wines either as a full-blown red or as a rosado.

I was able to pick up a bottle of the German Gilabert NV rosado Cava from my friends at Curtis Liquors for around $15. The blend for this wine was 85% Trepat and 15% Garnacha. The wine was aged for 10 months on the lees before disgorgement, and it is a Brut Nature Cava, which means that there is no dosage (a measure of wine and sugar typically added to sparkling wines right before final corking) added prior to bottling so the wine is very dry. The wine had a rich pink color in the glass with lively bubbles and aromas of light strawberry and raspberry fruit. On the palate, the wine was very dry with high acid and toasty strawberry/raspberry fruit. If you're looking for depth and complexity, keep looking because the name of the game here is clean, refreshing red-berry fruit with a few of the secondary aromas that you get with bottle fermented wines. This is a big value wine, as most Cava is. I'm not aware of any other kind of traditional-method sparkling wine in the $10-$20 range that is more consistently drinkable (if rarely great). It can be enjoyed on its own but the intense dryness here makes me want to have this with food more than I want to sip it alone. I had mine with a ham that I cooked for Easter dinner and it was a very nice match. I could also see this with some sushi or with a nice cheese plate.

But not all Cava is made from white grapes. There are rosado Cavas available as well and the grapes permitted in those wines are Garnacha (Grenache), Monsatrell (Mourvedre), Pinot Noir and Trepat. Three of those grapes should be pretty recognizable to the average, informed wine consumer, as they have homes elsewhere in the world where they get to be shining stars, but Trepat? What the heck is Trepat?

My first line of attack in most of my research is the Oxford Companion to Wine, which is not particularly helpful when it comes to Trepat. The book's entry reads in full: "indigenous red wine grape of north east Spain, particularly in Conca de Barberá and Costers del Segre. About 1,500 ha/3,700 acres are grown, used mainly for light rosés, but it has shown some intriguing potential for fine reds." A little extra digging shows that Trepat is picky about the soils it thrives in (it's not a fan of calcium-rich soils), though it does appear to be pretty resistant to most fungal diseases. It buds early and is thus susceptible to frost damage, which is more of a problem in this region at some of the higher altitudes, but Trepat is generally planted on lower-altitude sites. There are a few sources that say that there is as little as1,000 ha of Trepat planted, and I'm not aware of any plantings outside of Spain. The overwhelming majority of the grapes grown are used in the production of rosado Cava, though there are a few producers who do make a still wines either as a full-blown red or as a rosado.

I was able to pick up a bottle of the German Gilabert NV rosado Cava from my friends at Curtis Liquors for around $15. The blend for this wine was 85% Trepat and 15% Garnacha. The wine was aged for 10 months on the lees before disgorgement, and it is a Brut Nature Cava, which means that there is no dosage (a measure of wine and sugar typically added to sparkling wines right before final corking) added prior to bottling so the wine is very dry. The wine had a rich pink color in the glass with lively bubbles and aromas of light strawberry and raspberry fruit. On the palate, the wine was very dry with high acid and toasty strawberry/raspberry fruit. If you're looking for depth and complexity, keep looking because the name of the game here is clean, refreshing red-berry fruit with a few of the secondary aromas that you get with bottle fermented wines. This is a big value wine, as most Cava is. I'm not aware of any other kind of traditional-method sparkling wine in the $10-$20 range that is more consistently drinkable (if rarely great). It can be enjoyed on its own but the intense dryness here makes me want to have this with food more than I want to sip it alone. I had mine with a ham that I cooked for Easter dinner and it was a very nice match. I could also see this with some sushi or with a nice cheese plate.

Monday, May 23, 2011

Kerner - Valle Isarco, Alto Adige, Italy

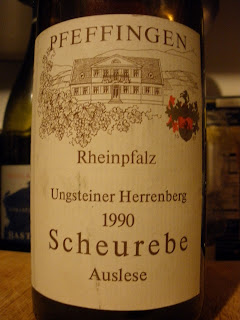

By all accounts, today's post should take us back into Germany. After all, the Kerner grape was created in 1929 by August Herold in Lauffen, Germany, by crossing Riesling and Schiava (also known as Trollinger or Vernatsch). In the mid-90's, Kerner was the third most planted white grape in Germany and occupied about 8,000 hectares of land, accounting for about 7.5% of total German vineyard land. Plantings have fallen in recent years, though, and Kerner today accounts for about 4% of total German vineyard area, placing it eighth among German white grapes. For comparison's sake, Scheurebe accounts for less than 2% of vineyard area, and German Scheurebe, while not exactly everywhere, is easier to find than German Kerner for some reason. In fact, both of the wines I'll be writing about today are from Alto Adige in Italy and every Kerner that I've seen on the shelf has been from this same region.

Why might that be? Well, I think it has something to do with the image of each country in the mind of the American consumer (it may be more widespread than that, but I'm not going to presume on behalf of other nationalities...I hesitate even here to generalize about the "American consumer"). As mentioned in the Scheurebe post, when you have a look at the German section of your local wine shop, I'm guessing that an overwhelming majority of the bottles on the shelf are Riesling even though Riesling itself only accounts for 22% of the vineyard area in Germany (most shops I frequent run between 90 - 100% Riesling in their German sections). I suspect that American consumers have associated Germany with Riesling to such an extent that there just isn't a lot of interest over here for wines made from other grapes, even though Germany certainly has a wealth of them. Italy, on the other hand, has kind of a reputation for wines made from all kinds of different grapes, so consumers are probably more willing to take a chance on a grape they've never heard of from Italy. In fact, the Italian landscape of grapes almost forces consumers to be open to variety unless they want to drink only Chianti for the rest of their life. I get a sense that for most people, Germany is practically equivalent to Riesling (or, worse, Liebfraumilch), so wine made from others grapes are a tougher sell. I've actually had more luck finding Müller-Thurgau wines from Italy than I have from Germany, and Müller-Thurgau is Germany's second most planted white grape, accounting for nearly 14% of the total vineyard surface!

So even if we grant that my little theory has some merit, some may still be scratching their heads and wondering what German grapes like Kerner and Müller-Thurgau are doing in Italy in the first place. Well, as mentioned in the post about Schiava, the Alto Adige region is on the northern border of Italy and, historically, has been under the control of the Austro-Hungarian empire (the territory was ceded to Italy only as recently as the end of World War I). The culture here is very Germanic and many of the grape varieties grown here reflect that. Kerner seems to have a special affinity for a sub-region in the north-central part of Alto Adige called Valle Isarco which sits directly on the border with Austria. This is Alpine country, though the areas right around the Isarco river are a little lower as the river has carved out the valley over time. Many of the vineyards here are at altitude, though, ranging from 500 - 1000 meters above sea level. As you might expect, this is definitely white wine country and Kerner seems to grow particularly well on these elevated slopes.

Most crossings are created to deal with specific climatic conditions and Kerner is no exception. It buds late so it misses most of the spring frosts, which is a big deal in the climates it inhabits. It does not have any specific soil requirements and is not particularly susceptible to any of the major moisture-related diseases that prey on vines (molds, rots, etc.). Like pretty much all successful crossings, Kerner can yield very large crops which, if left unchecked, can create thin, dilute wines. If properly managed in the vineyard and if given enough time to ripen fully (it is often not fully ripe until well into October), it can create exotically perfumed wines that resemble Riesling.

The first wine I was able to try was from the Cantina Valle Isarco, a cooperative within the Valle Isarco with over 130 members. The word "Eisacktaler" on the label is the Germanic term for the Valle Isarco region. The vintage on my bottle was 2006 and I paid about $18 for it. In the glass, the wine was a lemon yellow color with aromas of petrol, melon and honeysuckle. "Oily flowers" was the sum-up phrase I used for the nose. On the palate, the wine was dry with a rich, oily texture and medium acidity. There were lean fruit flavors of white peaches with honey and a touch of leafy mint on the finish. There was a nice, flinty kind of minerality running through the wine as well. The petrol aromas and flavors were pretty strong here and I'd guess this wine probably didn't have a lot of time left before it fell apart completely. If the acid level were a little higher here, this would be a fantastic wine, but the rich, oily texture didn't have much to support it. The alcohol here is also sky high for a white wine, clocking in at a monstrous 14.5%. This wine was certainly made from very ripe grapes and was pretty good, considering its age. This had the body to stand up to a lot, but I'd avoid foods with acidity as they'd probably make this taste a little flabbier than it really is. Thick sauces or chicken or pork are probably the ticket here.

The second wine I was able to try was from the Abbazia di Novacella winery. The vintage was 2009 and the price was $22. In the glass, this was a medium lemon green color with intense aromatics of grapefruit, lemon, melon and a touch of grassy herbs. The body was on the fuller side of medium with the same thick, oily texture as the prior bottle. The acid level was medium and there were flavors of ripe melon and grapefruit pith with a touch of lemony citrus. Considering how aromatic the wine was, it was a bit of a letdown on the palate as that exuberance didn't really carry over. The alcohol was very high here again (14%) and was much more obvious and in the way than on the previous bottle. All in all, this reminded me more of a Sancerre style Sauvignon Blanc than a Riesling which makes me wonder whether these grapes were a little underripe or whether they may something else blended in here (the DOC regulations stipulate that if a varietal is stated, the wine only needs to be comprised of 85 - 100% of that varietal with the rest made up of "other local similar varietals"). My money's on slightly underripe grapes, for what it's worth, and I would consider pairing this the same way I would the wine above, really, as it still had the big body with the lackluster acidity.

All in all, Kerner probably isn't going to replace Riesling any time soon, but it is a refreshing change of pace. I'd recommend drinking these wines young and pairing them with fairly hefty dishes that aren't particularly acidic. Also, because of the body and the high alcohol content, these feel more like autumn or winter weather whites to me, as they're not all that refreshing to drink on their own. Alto Adige has plenty of light zippy wines that will serve you better for the warm months ahead.

Why might that be? Well, I think it has something to do with the image of each country in the mind of the American consumer (it may be more widespread than that, but I'm not going to presume on behalf of other nationalities...I hesitate even here to generalize about the "American consumer"). As mentioned in the Scheurebe post, when you have a look at the German section of your local wine shop, I'm guessing that an overwhelming majority of the bottles on the shelf are Riesling even though Riesling itself only accounts for 22% of the vineyard area in Germany (most shops I frequent run between 90 - 100% Riesling in their German sections). I suspect that American consumers have associated Germany with Riesling to such an extent that there just isn't a lot of interest over here for wines made from other grapes, even though Germany certainly has a wealth of them. Italy, on the other hand, has kind of a reputation for wines made from all kinds of different grapes, so consumers are probably more willing to take a chance on a grape they've never heard of from Italy. In fact, the Italian landscape of grapes almost forces consumers to be open to variety unless they want to drink only Chianti for the rest of their life. I get a sense that for most people, Germany is practically equivalent to Riesling (or, worse, Liebfraumilch), so wine made from others grapes are a tougher sell. I've actually had more luck finding Müller-Thurgau wines from Italy than I have from Germany, and Müller-Thurgau is Germany's second most planted white grape, accounting for nearly 14% of the total vineyard surface!

So even if we grant that my little theory has some merit, some may still be scratching their heads and wondering what German grapes like Kerner and Müller-Thurgau are doing in Italy in the first place. Well, as mentioned in the post about Schiava, the Alto Adige region is on the northern border of Italy and, historically, has been under the control of the Austro-Hungarian empire (the territory was ceded to Italy only as recently as the end of World War I). The culture here is very Germanic and many of the grape varieties grown here reflect that. Kerner seems to have a special affinity for a sub-region in the north-central part of Alto Adige called Valle Isarco which sits directly on the border with Austria. This is Alpine country, though the areas right around the Isarco river are a little lower as the river has carved out the valley over time. Many of the vineyards here are at altitude, though, ranging from 500 - 1000 meters above sea level. As you might expect, this is definitely white wine country and Kerner seems to grow particularly well on these elevated slopes.

Most crossings are created to deal with specific climatic conditions and Kerner is no exception. It buds late so it misses most of the spring frosts, which is a big deal in the climates it inhabits. It does not have any specific soil requirements and is not particularly susceptible to any of the major moisture-related diseases that prey on vines (molds, rots, etc.). Like pretty much all successful crossings, Kerner can yield very large crops which, if left unchecked, can create thin, dilute wines. If properly managed in the vineyard and if given enough time to ripen fully (it is often not fully ripe until well into October), it can create exotically perfumed wines that resemble Riesling.

The first wine I was able to try was from the Cantina Valle Isarco, a cooperative within the Valle Isarco with over 130 members. The word "Eisacktaler" on the label is the Germanic term for the Valle Isarco region. The vintage on my bottle was 2006 and I paid about $18 for it. In the glass, the wine was a lemon yellow color with aromas of petrol, melon and honeysuckle. "Oily flowers" was the sum-up phrase I used for the nose. On the palate, the wine was dry with a rich, oily texture and medium acidity. There were lean fruit flavors of white peaches with honey and a touch of leafy mint on the finish. There was a nice, flinty kind of minerality running through the wine as well. The petrol aromas and flavors were pretty strong here and I'd guess this wine probably didn't have a lot of time left before it fell apart completely. If the acid level were a little higher here, this would be a fantastic wine, but the rich, oily texture didn't have much to support it. The alcohol here is also sky high for a white wine, clocking in at a monstrous 14.5%. This wine was certainly made from very ripe grapes and was pretty good, considering its age. This had the body to stand up to a lot, but I'd avoid foods with acidity as they'd probably make this taste a little flabbier than it really is. Thick sauces or chicken or pork are probably the ticket here.

The second wine I was able to try was from the Abbazia di Novacella winery. The vintage was 2009 and the price was $22. In the glass, this was a medium lemon green color with intense aromatics of grapefruit, lemon, melon and a touch of grassy herbs. The body was on the fuller side of medium with the same thick, oily texture as the prior bottle. The acid level was medium and there were flavors of ripe melon and grapefruit pith with a touch of lemony citrus. Considering how aromatic the wine was, it was a bit of a letdown on the palate as that exuberance didn't really carry over. The alcohol was very high here again (14%) and was much more obvious and in the way than on the previous bottle. All in all, this reminded me more of a Sancerre style Sauvignon Blanc than a Riesling which makes me wonder whether these grapes were a little underripe or whether they may something else blended in here (the DOC regulations stipulate that if a varietal is stated, the wine only needs to be comprised of 85 - 100% of that varietal with the rest made up of "other local similar varietals"). My money's on slightly underripe grapes, for what it's worth, and I would consider pairing this the same way I would the wine above, really, as it still had the big body with the lackluster acidity.

All in all, Kerner probably isn't going to replace Riesling any time soon, but it is a refreshing change of pace. I'd recommend drinking these wines young and pairing them with fairly hefty dishes that aren't particularly acidic. Also, because of the body and the high alcohol content, these feel more like autumn or winter weather whites to me, as they're not all that refreshing to drink on their own. Alto Adige has plenty of light zippy wines that will serve you better for the warm months ahead.

Friday, May 20, 2011

Monica - Sardinia, Italy

Insularity is an interesting phenomenon. We usually consider a group to be insular when they're tightly-knit and close with one another while being suspicious and closed minded about people and ideas that come from outside of their group. Generally speaking, insularity is a bad thing since, at its worst, it promotes intolerance and distrust (think of cults or hate groups like Westboro Baptist Church). Insularity is typically a result of some kind of isolation and for most of the groups that we negatively associate insularity with, ideological isolation is the root cause. Ideological isolation typically occurs when a group shares a set of beliefs that is radically out of step with the culture they share a geographical proximity with (or are located within). This proximity is key as insularity becomes a kind of defense mechanism to keep the ideologies of the group intact against the constant threat of other nearby groups or prevalent ideas within the community at large that are threatening to that group's own ideological base. These constant threats can create aggression as the group seeks to protect their own beliefs through attack. When you believe that you are surrounded and under attack, it often seems like the best defense is to come out firing.

But insularity isn't necessarily all bad. In its more benign forms, insularity can act as a preservative for unique and interesting ideas or ways of life. For this type of insularity, geographical isolation is the driving force. Geographically isolated communities become insular by virtue of their distance from other groups and cultures which allows them to carry on their own traditions without much threat from outside forces or influences. Rather than aggression, provincialism or parochialism seem to be the biggest drawbacks to insular communities formed in geographical isolation.

All of which leads us to Sardinia, which is literally insular, as the primary meaning of insular is "of, pertaining to, or resembling an island or islands." Sardinia is located a little over 100 miles off the western coast of Italy, though it is less than ten miles from the French island of Corsica to its north. Though it is surrounded by water today, millions of years ago it was connected to the mainland of Italy by a series of isthmuses. It has been occupied by a laundry list of foreign powers, but never really been conquered. The interior of the island is very hilly and most locals are content to farm and shepherd there. Most occupiers were almost certainly more interested in Sardinia as a naval base and since the coastline was never a big part of Sardinian life, for the most part, it seems, each side let the other be.

Sardinia is the second largest island in the Mediterranean Sea behind Sicily. Like Sicily, Sardinia has its own local dialect called Sardo that may as well be a language unto itself. Unlike Sicily, though, wine production in Sardinia is not that high. Sicily tends to be near the top of Italian regions in terms of production and is responsible for about one-sixth of Italy's total output. Sardinia, on the other hand, only produces about two percent of Italy's total (which amounts to only about 10% of Sicily's total) even though it is its third largest region by area. The dominant agricultural crop in Sardinia was grain for many years and the focus on viticulture has really come around only in the last 60 years or so. Wine has been made here for a long time, but for many years it was sweet and fortified wine, since their location made it necessary for them to produce wine that could survive travel well. The focus on table wines for external markets is a very new phenomenon here, taking off really around the late 1970's.

Sardinia is the second largest island in the Mediterranean Sea behind Sicily. Like Sicily, Sardinia has its own local dialect called Sardo that may as well be a language unto itself. Unlike Sicily, though, wine production in Sardinia is not that high. Sicily tends to be near the top of Italian regions in terms of production and is responsible for about one-sixth of Italy's total output. Sardinia, on the other hand, only produces about two percent of Italy's total (which amounts to only about 10% of Sicily's total) even though it is its third largest region by area. The dominant agricultural crop in Sardinia was grain for many years and the focus on viticulture has really come around only in the last 60 years or so. Wine has been made here for a long time, but for many years it was sweet and fortified wine, since their location made it necessary for them to produce wine that could survive travel well. The focus on table wines for external markets is a very new phenomenon here, taking off really around the late 1970's.

Sardinia has a wealth of native grape varieties that aren't grown anywhere else on earth (part of geographical insularity and isolation is an abundance of unique native species, as any student of Darwin can tell you). We'll get around to some of them (like Nuragus and Torbato) in later posts, but the grape in question today is the Monica grape. Monica is native to Spain though it is seldom grown there today. Conquistadors from Spain arrived in Sardinia around the 13th Century and hung around for awhile. During their occupation many grape varieties were brought over from mainland Spain including Carignano (Carignan in France), Cannonau (Garnacha in Spain and Grenache in France), Monica and Bovale which is primarily a blending grape. Monica is widely grown on the southern half of the island, especially around the port town of Cagliari (pictured above) on the southern coast of Sardinia where it has its own small DOC area (there is a larger Monica di Sardegna DOC that covers the entire island as well).

If you are able to find Monica on American shelves, it is likely the bottling from Argiolas called Perdera. I was able to pick up a bottle of the 2008 vintage of this for around $13. This bottling is mostly Monica with some Bovale and Carignano making up the remaining portion. I had thought that the blend was 90/5/5, but this is bottled as an IGT rather than a DOC, and the only explanation I can think of is that there is less than 85% Monica in the bottle, which is the minimum for the DOC classification. If you go to the Argiolas website and read their factsheet, the wine is listed as a Monica di Sardegna DOC and a Google image search for the label seems to be split 50/50 between the two designations. I would guess that depending on how their crops do, they have to adjust the blend from year to year and hope they can use at least 85% Monica. The IGT listed is Isola dei Nuraghi which is a catch-all designation covering all of Sardinia. The Nuraghi mentioned in the IGT name are ancient stone tower-fortresses that can be found all over Sardinia (there are over 7,000 of them).

In any case, the wine had a medium purplish-ruby color in the glass with aromas of stewed cherries and raspberries with a kind of musty, damp earth undertone. It was on the lighter side of medium bodied with low tannins and medium plus acidity with tart cherry and stewed red fruit flavors. It had some dusky chocolate and earth wet earth flavors and bit of a bitter cranberry tang to it on the finish. This is definitely more on the Pinot Noir end of the spectrum than the Cabernet or Syrah end in terms of body and structure. It's a simple, easy going light red wine that, like so many Italian wines, really seems to want some food to go with it. Anything with tomatoes would be great here, as would some lighter meat dishes like turkey burgers or lean meatballs.

But insularity isn't necessarily all bad. In its more benign forms, insularity can act as a preservative for unique and interesting ideas or ways of life. For this type of insularity, geographical isolation is the driving force. Geographically isolated communities become insular by virtue of their distance from other groups and cultures which allows them to carry on their own traditions without much threat from outside forces or influences. Rather than aggression, provincialism or parochialism seem to be the biggest drawbacks to insular communities formed in geographical isolation.

All of which leads us to Sardinia, which is literally insular, as the primary meaning of insular is "of, pertaining to, or resembling an island or islands." Sardinia is located a little over 100 miles off the western coast of Italy, though it is less than ten miles from the French island of Corsica to its north. Though it is surrounded by water today, millions of years ago it was connected to the mainland of Italy by a series of isthmuses. It has been occupied by a laundry list of foreign powers, but never really been conquered. The interior of the island is very hilly and most locals are content to farm and shepherd there. Most occupiers were almost certainly more interested in Sardinia as a naval base and since the coastline was never a big part of Sardinian life, for the most part, it seems, each side let the other be.

Sardinia is the second largest island in the Mediterranean Sea behind Sicily. Like Sicily, Sardinia has its own local dialect called Sardo that may as well be a language unto itself. Unlike Sicily, though, wine production in Sardinia is not that high. Sicily tends to be near the top of Italian regions in terms of production and is responsible for about one-sixth of Italy's total output. Sardinia, on the other hand, only produces about two percent of Italy's total (which amounts to only about 10% of Sicily's total) even though it is its third largest region by area. The dominant agricultural crop in Sardinia was grain for many years and the focus on viticulture has really come around only in the last 60 years or so. Wine has been made here for a long time, but for many years it was sweet and fortified wine, since their location made it necessary for them to produce wine that could survive travel well. The focus on table wines for external markets is a very new phenomenon here, taking off really around the late 1970's.

Sardinia is the second largest island in the Mediterranean Sea behind Sicily. Like Sicily, Sardinia has its own local dialect called Sardo that may as well be a language unto itself. Unlike Sicily, though, wine production in Sardinia is not that high. Sicily tends to be near the top of Italian regions in terms of production and is responsible for about one-sixth of Italy's total output. Sardinia, on the other hand, only produces about two percent of Italy's total (which amounts to only about 10% of Sicily's total) even though it is its third largest region by area. The dominant agricultural crop in Sardinia was grain for many years and the focus on viticulture has really come around only in the last 60 years or so. Wine has been made here for a long time, but for many years it was sweet and fortified wine, since their location made it necessary for them to produce wine that could survive travel well. The focus on table wines for external markets is a very new phenomenon here, taking off really around the late 1970's.Sardinia has a wealth of native grape varieties that aren't grown anywhere else on earth (part of geographical insularity and isolation is an abundance of unique native species, as any student of Darwin can tell you). We'll get around to some of them (like Nuragus and Torbato) in later posts, but the grape in question today is the Monica grape. Monica is native to Spain though it is seldom grown there today. Conquistadors from Spain arrived in Sardinia around the 13th Century and hung around for awhile. During their occupation many grape varieties were brought over from mainland Spain including Carignano (Carignan in France), Cannonau (Garnacha in Spain and Grenache in France), Monica and Bovale which is primarily a blending grape. Monica is widely grown on the southern half of the island, especially around the port town of Cagliari (pictured above) on the southern coast of Sardinia where it has its own small DOC area (there is a larger Monica di Sardegna DOC that covers the entire island as well).

If you are able to find Monica on American shelves, it is likely the bottling from Argiolas called Perdera. I was able to pick up a bottle of the 2008 vintage of this for around $13. This bottling is mostly Monica with some Bovale and Carignano making up the remaining portion. I had thought that the blend was 90/5/5, but this is bottled as an IGT rather than a DOC, and the only explanation I can think of is that there is less than 85% Monica in the bottle, which is the minimum for the DOC classification. If you go to the Argiolas website and read their factsheet, the wine is listed as a Monica di Sardegna DOC and a Google image search for the label seems to be split 50/50 between the two designations. I would guess that depending on how their crops do, they have to adjust the blend from year to year and hope they can use at least 85% Monica. The IGT listed is Isola dei Nuraghi which is a catch-all designation covering all of Sardinia. The Nuraghi mentioned in the IGT name are ancient stone tower-fortresses that can be found all over Sardinia (there are over 7,000 of them).

In any case, the wine had a medium purplish-ruby color in the glass with aromas of stewed cherries and raspberries with a kind of musty, damp earth undertone. It was on the lighter side of medium bodied with low tannins and medium plus acidity with tart cherry and stewed red fruit flavors. It had some dusky chocolate and earth wet earth flavors and bit of a bitter cranberry tang to it on the finish. This is definitely more on the Pinot Noir end of the spectrum than the Cabernet or Syrah end in terms of body and structure. It's a simple, easy going light red wine that, like so many Italian wines, really seems to want some food to go with it. Anything with tomatoes would be great here, as would some lighter meat dishes like turkey burgers or lean meatballs.

Wednesday, May 18, 2011

Nosiola - Vignetti Delle Dolomiti, Italy

I remember well my first encounter with Nosiola. I was at one of those huge walk-around tastings at a local wine shop and was tasting through an importer's selection of Italian wines. Some guy I didn't know was doing the flight concurrently with me and when the pourer gave us a splash of Nosiola, a grape neither of us had ever heard of at the time, we gave it a tentative sniff and sip and kind of looked at one another out of the corners of our eyes. It smelled a little nutty and really didn't taste like much of anything. We both had the same thought: is this what it's supposed to taste like or is this flawed? After we politely queried the pourer about the soundness of the bottle, she poured herself a taste and told us that the bottle had just come off the ship the day before so it may be in a little shock, but for the most part, yes, this is really what this wine is like. My temporary companion and I shrugged and walked away. There weren't any bottles available for purchase at the tasting, and since the shop was pretty far from my home base, I didn't put in an order for any. The wine didn't really captivate me and I was content to walk away and put off the chance to write about it for another time. It was six months before I spotted any more Nosiola. Remembering my prior experience, I wasn't exactly thrilled with the find, but I was determined to give Nosiola a chance to win me over so I bought two bottles and tasted them on back to back nights.

Nosiola is a tough grape to write about. Oz Clarke calls it "unusually neutral," and that's a pretty good summation. There's very little information about it available, I'd guess, because it's a pretty forgettable grape. It's not the kind of thing you taste and get really excited about and rush out to tell the world. It seems to be native to Trentino and was first described in detail in 1825 by an Italian naturalist named Giusseppe Acerbi. The name derives from the Italian word for hazelnut, which is nocciola, and is so called because the wine can have some hazelnut characteristics in the nose (much of the info I have is from this site and while they say something about the color of the berries or stems or something, I can't quite parse what it is that they're getting at). The grape does well in hilly regions, which is good because the Dolomiti in the region name in the title of this post references the Dolomite mountain range in northern Italy. It buds early and so is susceptible to frost and is thin skinned and thus susceptible to grey rot (the bad Botrytis) and powdery mildew.

Nosiola is perhaps best known as the base of the Trentino version of Vin Santo (not to be confused with the similarly named but somewhat different Vin Santos of Greece). In Tuscany, most Vin Santo is blended from Trebbiano, Malvasia and a handful of other white grapes while in the Marche, the blend must be mostly from a grape called Passerina (which will be the subject of an upcoming post here). In Trentino, Vin Santo must be made from 100% Nosiola grapes that are dried on small mats, crushed and fermented and stored in very small wooden vessels for at least three years (though typically for longer). Wines made in this style are eligible to be bottled under the Trentino DOC appellation which, as far as I can tell, is one of only two DOCs in Italy that allow Nosiola to make up the majority or totality of the blend (the other is Sorni Bianco). Most varietal Nosiolas that you are likely to come across will be IGT bottlings and all of the ones that I've seen are bottled under the Vignetti Delle Dolomiti IGT which stretches across both Trentino and the Veneto.

The first bottle that I was able to find was the 2004 Castel Noarna which I picked up for around $19. I was curious to taste this wine to see if perhaps Nosiola would pick up some more interesting flavors from a little bottle age. In the glass, this wine was a medium gold color, definitely showing its age a bit. It had a distinctly nutty aroma like fresh hazelnuts or almonds and not much else. On the palate it was medium bodied with a surprising vein of acidity. There was a light lemony flavor along with slivered almonds and a clean minerality. As it warmed up, it seemed to pick up a kind of buttery flavor but on the whole, it was pretty neutral. I was surprised at how well it had held up since this isn't a grape that is typically known for its acidity and aging potential. My suspicion is that there just isn't that much that can fade from Nosiola in the first place, so aging it really isn't much of a risky endeavor. It reminded me a little of a Fino Sherry (though not nearly as overwhelmingly nutty) and the same kinds of pairings that work with that wine would probably work well here also. I'm thinking aperitif or salted nuts or something in that vein.

The second wine that I tried was the 2008 Gino Pedrotti Nosiola which I picked up from my friends at Curtis Liquors for around $18. If the label looks a little familiar it's because I've written about this producer's Schiava here before. In the glass, the wine had a medium lemon color with aromas of green apple and lemon peel. The nose was somewhat elusive as it was markedly present on a first whiff, but I found myself acclimating to it very quickly. You kind of have to sniff it and then walk away for a minute and come back to it to really get at it. On the palate the wine was medium bodied with medium acidity. It had light minerally lemon and a kind of candied green apple flavor. The nutty aromas and flavors that were the hallmark of the prior wine were largely absent here though the general sense of neutrality was not. There was more primary fruit here (relatively speaking) so perhaps the nuttiness comes out a bit more with some time in the bottle. This wine would be an adequate companion to a lot of foods, but I wouldn't expect that it would really heighten or intensify very many dishes. Neutral wines do occasionally have their place at the table so if you're in the market for that kind of wine, Nosiola may be your new best friend. At those price points, though, it's probably not a wine I'll be spending a lot of time with in the future.

Nosiola is a tough grape to write about. Oz Clarke calls it "unusually neutral," and that's a pretty good summation. There's very little information about it available, I'd guess, because it's a pretty forgettable grape. It's not the kind of thing you taste and get really excited about and rush out to tell the world. It seems to be native to Trentino and was first described in detail in 1825 by an Italian naturalist named Giusseppe Acerbi. The name derives from the Italian word for hazelnut, which is nocciola, and is so called because the wine can have some hazelnut characteristics in the nose (much of the info I have is from this site and while they say something about the color of the berries or stems or something, I can't quite parse what it is that they're getting at). The grape does well in hilly regions, which is good because the Dolomiti in the region name in the title of this post references the Dolomite mountain range in northern Italy. It buds early and so is susceptible to frost and is thin skinned and thus susceptible to grey rot (the bad Botrytis) and powdery mildew.

Nosiola is perhaps best known as the base of the Trentino version of Vin Santo (not to be confused with the similarly named but somewhat different Vin Santos of Greece). In Tuscany, most Vin Santo is blended from Trebbiano, Malvasia and a handful of other white grapes while in the Marche, the blend must be mostly from a grape called Passerina (which will be the subject of an upcoming post here). In Trentino, Vin Santo must be made from 100% Nosiola grapes that are dried on small mats, crushed and fermented and stored in very small wooden vessels for at least three years (though typically for longer). Wines made in this style are eligible to be bottled under the Trentino DOC appellation which, as far as I can tell, is one of only two DOCs in Italy that allow Nosiola to make up the majority or totality of the blend (the other is Sorni Bianco). Most varietal Nosiolas that you are likely to come across will be IGT bottlings and all of the ones that I've seen are bottled under the Vignetti Delle Dolomiti IGT which stretches across both Trentino and the Veneto.

The first bottle that I was able to find was the 2004 Castel Noarna which I picked up for around $19. I was curious to taste this wine to see if perhaps Nosiola would pick up some more interesting flavors from a little bottle age. In the glass, this wine was a medium gold color, definitely showing its age a bit. It had a distinctly nutty aroma like fresh hazelnuts or almonds and not much else. On the palate it was medium bodied with a surprising vein of acidity. There was a light lemony flavor along with slivered almonds and a clean minerality. As it warmed up, it seemed to pick up a kind of buttery flavor but on the whole, it was pretty neutral. I was surprised at how well it had held up since this isn't a grape that is typically known for its acidity and aging potential. My suspicion is that there just isn't that much that can fade from Nosiola in the first place, so aging it really isn't much of a risky endeavor. It reminded me a little of a Fino Sherry (though not nearly as overwhelmingly nutty) and the same kinds of pairings that work with that wine would probably work well here also. I'm thinking aperitif or salted nuts or something in that vein.

The second wine that I tried was the 2008 Gino Pedrotti Nosiola which I picked up from my friends at Curtis Liquors for around $18. If the label looks a little familiar it's because I've written about this producer's Schiava here before. In the glass, the wine had a medium lemon color with aromas of green apple and lemon peel. The nose was somewhat elusive as it was markedly present on a first whiff, but I found myself acclimating to it very quickly. You kind of have to sniff it and then walk away for a minute and come back to it to really get at it. On the palate the wine was medium bodied with medium acidity. It had light minerally lemon and a kind of candied green apple flavor. The nutty aromas and flavors that were the hallmark of the prior wine were largely absent here though the general sense of neutrality was not. There was more primary fruit here (relatively speaking) so perhaps the nuttiness comes out a bit more with some time in the bottle. This wine would be an adequate companion to a lot of foods, but I wouldn't expect that it would really heighten or intensify very many dishes. Neutral wines do occasionally have their place at the table so if you're in the market for that kind of wine, Nosiola may be your new best friend. At those price points, though, it's probably not a wine I'll be spending a lot of time with in the future.

Monday, May 16, 2011

Crémant de Jura Rosé - Jura, France

After attending a great tasting of wines from the Jura at The Wine Bottega in the North End of Boston last week, I decided to finally turn my attention to a tasting note for a Crémant de Jura that's been sitting in my notebook for awhile. I keep looking at this note and putting it off in favor of another topic and just have had a difficult time working up the motivation to write about it. It's not that it is isn't an interesting wine. In fact, it has pretty much all three Fringe Wine components working for it: unusual grapes (Trousseau and Poulsard), unusual region and unusual style (most Crémant de Jura is made from Chardonnay in a Blanc de Blancs style). No, my hesitation stemmed from something a little more personal: I'm a terrible sparkling wine taster.

More specifically, I guess, I'm a terrible taster of sparkling wines made using the traditional Champagne method. The secondary flavor characteristics from lees aging coupled with the bubbles form a tag team that I have difficulty penetrating. Charmat method wines don't give me as much trouble but it's still tough for me to taste past the bubbles. Don't get me wrong, I love sparkling wines and enjoy them every opportunity I get, but the nuances are mostly lost on me (unlike my fellow Boston-area blogger Dale Cruse whose blog is essential reading for bubbly fans). The only remedy, I've decided, is to keep plugging away and work my way through it (the ultimate torture, I know: drink more sparkling wine).

So, anyway, about that Crémant de Jura. The Jura is a small region in France, east of Burgundy, on the border with Switzerland. It's a little farther north than Savoie and is less geologically rugged as the Jura mountains are more sylvan and resemble rolling hills more than capital-M Mountains. There are five different grape varieties used in the Jura: Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Trousseau, Poulsard (sometimes called Ploussard) and Savagnin. The red wines from here are usually very light in both color and body and Pinot Noir is actually used to darken the wines made from Poulsard and Trousseau. The white wines are usually a little heftier, are served after the reds in a tasting, and are often intentionally oxidized to some extent (to greatest effect in the region's vin jaune offerings). Production is not particularly voluminous here and when you couple that with the off-beat style of many of the offerings, it translates into limited exposure in the US market. Word is spreading about these wines, though, and though they're still not omnipresent, they are showing up in more shops and are well worth the search.

The bottle I was able to find was from Domaine Rolet Pere et Fils. It's a non-vintage bottling that I got for around $19 from my friends at Bin Ends. The grapes featured in this rosé sparkler were Poulsard, Trousseau and Pinot Noir and Fringe Wine regulars may note that I didn't write about the grapes in the body of the post. I skipped it this time not out of negligence but because I have single varietal bottlings of Poulsard and Trousseau that I picked up at the Jura tasting that will be written up soon. Suffice to say for now that Poulsard is a very thin-skinned red grape that gives very little color, and Trousseau is also known as Bastardo in Portugal where it is a permitted grape in the Port blend but is not considered one of the five noble port grapes. In the glass this had a pale salmon color and a nice, steady bead. The nose was fruity with some strawberry and toast but not much else. The wine was dry with high acidity, a creamy mousse, some nice strawberry fruit, and some toasty notes. This was a relatively straightforward rosé sparkler that hit just a few notes, but hit them pretty well. I had this with an Alfredo sauced pasta dish and found that it served very admirably as an accompaniment. This particular bottling from the Jura probably won't change your life or anything, but it is a nice, accessible introduction to a very unique and interesting region in France.

I also would like to point out that I have written the section on the Jura for AG Wine's iPhone app. The piece is currently in the final editing stages and should be up on the app soon. If you buy the app now, you will receive all future updates with new regions for free. You can check out AG Wine's website here or you can go here to download the app for your iPhone or iPad. It's definitely one of the most informative and useful wine apps that I've used and I enthusiastically recommend it for people interested in learning more about wine and less about wine scores. I've also written the section on Alsace and the upcoming section for Savoie as well. Their free Wine News app also syndicates my posts so you can follow Fringe Wine and many other great writers on the go for free. In the interest of full disclosure, I do not receive any financial compensation from AG Wine for any of the content or promotion that I provide to them.

More specifically, I guess, I'm a terrible taster of sparkling wines made using the traditional Champagne method. The secondary flavor characteristics from lees aging coupled with the bubbles form a tag team that I have difficulty penetrating. Charmat method wines don't give me as much trouble but it's still tough for me to taste past the bubbles. Don't get me wrong, I love sparkling wines and enjoy them every opportunity I get, but the nuances are mostly lost on me (unlike my fellow Boston-area blogger Dale Cruse whose blog is essential reading for bubbly fans). The only remedy, I've decided, is to keep plugging away and work my way through it (the ultimate torture, I know: drink more sparkling wine).

So, anyway, about that Crémant de Jura. The Jura is a small region in France, east of Burgundy, on the border with Switzerland. It's a little farther north than Savoie and is less geologically rugged as the Jura mountains are more sylvan and resemble rolling hills more than capital-M Mountains. There are five different grape varieties used in the Jura: Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Trousseau, Poulsard (sometimes called Ploussard) and Savagnin. The red wines from here are usually very light in both color and body and Pinot Noir is actually used to darken the wines made from Poulsard and Trousseau. The white wines are usually a little heftier, are served after the reds in a tasting, and are often intentionally oxidized to some extent (to greatest effect in the region's vin jaune offerings). Production is not particularly voluminous here and when you couple that with the off-beat style of many of the offerings, it translates into limited exposure in the US market. Word is spreading about these wines, though, and though they're still not omnipresent, they are showing up in more shops and are well worth the search.

The bottle I was able to find was from Domaine Rolet Pere et Fils. It's a non-vintage bottling that I got for around $19 from my friends at Bin Ends. The grapes featured in this rosé sparkler were Poulsard, Trousseau and Pinot Noir and Fringe Wine regulars may note that I didn't write about the grapes in the body of the post. I skipped it this time not out of negligence but because I have single varietal bottlings of Poulsard and Trousseau that I picked up at the Jura tasting that will be written up soon. Suffice to say for now that Poulsard is a very thin-skinned red grape that gives very little color, and Trousseau is also known as Bastardo in Portugal where it is a permitted grape in the Port blend but is not considered one of the five noble port grapes. In the glass this had a pale salmon color and a nice, steady bead. The nose was fruity with some strawberry and toast but not much else. The wine was dry with high acidity, a creamy mousse, some nice strawberry fruit, and some toasty notes. This was a relatively straightforward rosé sparkler that hit just a few notes, but hit them pretty well. I had this with an Alfredo sauced pasta dish and found that it served very admirably as an accompaniment. This particular bottling from the Jura probably won't change your life or anything, but it is a nice, accessible introduction to a very unique and interesting region in France.

I also would like to point out that I have written the section on the Jura for AG Wine's iPhone app. The piece is currently in the final editing stages and should be up on the app soon. If you buy the app now, you will receive all future updates with new regions for free. You can check out AG Wine's website here or you can go here to download the app for your iPhone or iPad. It's definitely one of the most informative and useful wine apps that I've used and I enthusiastically recommend it for people interested in learning more about wine and less about wine scores. I've also written the section on Alsace and the upcoming section for Savoie as well. Their free Wine News app also syndicates my posts so you can follow Fringe Wine and many other great writers on the go for free. In the interest of full disclosure, I do not receive any financial compensation from AG Wine for any of the content or promotion that I provide to them.

Wednesday, May 11, 2011

Xinomavro - Naoussa, Greece

Xinomavro just sounds exotic. You look at the word with all those rare consonants and rolling syllables and it just feels different somehow. I was reading through a few wine sites' April Fools posts this past year and the grape that was mentioned the most in their joke posts was Xinomavro by a fairly large margin. Let's face it: there just aren't that many words that start with the letter "X" and there certainly aren't very many grapes that do either. While it's certainly not the most obscure grape on the planet, it sure sounds like it should be. I've briefly covered Xinomavro on this site before, though I wrote about a white wine produced from the grape. Since I wrote that post, I've found that there are some white wines made from the Xinomavro grape, but the most exciting examples are universally red.

Xinomavro is found mostly in the Imathia subregion of Macedonia in northern Greece. Within Imathia is the town of Naoussa where the best Xinomavros are made. It can be a little tough to find Xinomavro wines because the grapes is not usually mentioned on the label, but rest assured if your label says "Naoussa" then you're in very good shape as this area is a monoculture and does not produce wine from any other grape. The name Naoussa is a Greek corruption of the Roman name for the village, "Nova Augusta," and the region has produced wine for thousands of years. When the Ottomans took over Greece, the townspeople of Naoussa were able to negotiate some particularly favorable deals with them and they were able to keep and maintain their vineyards for the duration of the Ottoman occupation (since the Ottomans were Muslim, many regions in Greece were forced to abandon wine production in order to comply with Ottoman religious custom). Political struggles between local leaders and a disastrous revolt against the Ottoman occupiers in the early part of the 18th Century were major setbacks for the region as they exacted serious financial, territorial and human tolls on the region. They've since rebounded nicely and the region was given Appellation status in 1971.

Xinomavro itself is a finicky grape to grow. It doesn't like very dry conditions, is susceptible to several fungal diseases, and is very sensitive to soil types, planting densities and canopy management. There are also many different clones of the grape which differ markedly from one another in virtually every way that you can think of. They flower and ripen at different times, have different bunch and berry sizes, have different vinous characteristics (fruit, acidity and tannin) and reach their peak ripeness in different microclimates. No one clone seems to have the magic combination so many different clones are grown on different sites and blended together in the winery. Once you get past all the growing troubles and issues in the winery (many clones have poor color stability and can create very odd aromas when vinified), the wine that you get tends to be fairly light in color and very high and acidity and tannin. In short, it is the polar opposite of the kind of wine that is very much in fashion right now in that it's not very accessible in its youth and tends to demand food. Needless to say, Xinomavro is facing several uphill battles in the world marketplace.

But is it all worth it? I was able to sample two different bottlings from the same producer in order to find that out. The first wine I tried was the basic Boutari Naoussa bottling. I picked up a bottle of the 2007 vintage for around $18. The wine had a light ruby color in the glass and and a generous nose of crushed red berries, stewed cherries, rich raspberry and some redcurrant with kind of a leafy, herbal edge. There was kind of a chocolate note in it too, like a chocolate covered dried cherry. The texture was a little thin and the wine had a very high acidity and very grippy tannins. I've seen a lot of comparisons between Xinomavro and Pinot Noir, but I definitely agree more with Konstantinos Lazarakis (in his The Wines of Greece) in that I think the more appropriate comparison is with Nebbiolo based wines from the Piedmont. This wine demands food (think meats and pretty much anything you'd serve with a Barolo) and has the structure to age for awhile yet.

The second wine I tried was also from Boutari, but it was their Grand Reserve bottling. I grabbed the 2003 vintage of this for about $40. The Grand Reserve level from Boutari are held for a few years before they are released. They see two years in oak barrels that are a little larger than the barriques used in most of the world (those hold about 225 liters while the ones at Boutari are either 400 or 500 liter barrels), half of which are new oak and the other half neutral oak. They are aged an additional two years in bottle. In the glass, this was a very pale violet color with little saturation. The nose had a spicy, woody kind of aroma with redcurrant, stewed tomatoes, crushed sage, tobacco and old leather. The wine was medium bodied with high acid and high tannins (again, this is a food wine and not an afternoon sipper). The fruits were faded pretty badly from this with just a vague sense of raspberryish red fruit along with dried sage and something a little floral. Though the nose was more interesting and complex on this wine, the palate was not as generous as the entry level Naoussa wine and I don't know if it was in a dumb phase or whether this was just an off-year (Greek wine vintage charts aren't very common). It's not that it was a bad wine, but for the money I'd much rather drink the entry level Naoussa bottling rather than run the risk of a bad vintage of the Grand Reserve, especially since Xinomavro is so finicky in the vineyard and very susceptible to vintage variations. These Grand Reserve bottlings are famously long-lived (from good years, anyway) so I'd like to have a chance to taste one with about 10 years of age on it and see how it's doing at that point. In the meantime, if you're in the mood for something Barolo-like but don't want to fork over Barolo bucks, give Xinomavro a shot.

Xinomavro is found mostly in the Imathia subregion of Macedonia in northern Greece. Within Imathia is the town of Naoussa where the best Xinomavros are made. It can be a little tough to find Xinomavro wines because the grapes is not usually mentioned on the label, but rest assured if your label says "Naoussa" then you're in very good shape as this area is a monoculture and does not produce wine from any other grape. The name Naoussa is a Greek corruption of the Roman name for the village, "Nova Augusta," and the region has produced wine for thousands of years. When the Ottomans took over Greece, the townspeople of Naoussa were able to negotiate some particularly favorable deals with them and they were able to keep and maintain their vineyards for the duration of the Ottoman occupation (since the Ottomans were Muslim, many regions in Greece were forced to abandon wine production in order to comply with Ottoman religious custom). Political struggles between local leaders and a disastrous revolt against the Ottoman occupiers in the early part of the 18th Century were major setbacks for the region as they exacted serious financial, territorial and human tolls on the region. They've since rebounded nicely and the region was given Appellation status in 1971.

Xinomavro itself is a finicky grape to grow. It doesn't like very dry conditions, is susceptible to several fungal diseases, and is very sensitive to soil types, planting densities and canopy management. There are also many different clones of the grape which differ markedly from one another in virtually every way that you can think of. They flower and ripen at different times, have different bunch and berry sizes, have different vinous characteristics (fruit, acidity and tannin) and reach their peak ripeness in different microclimates. No one clone seems to have the magic combination so many different clones are grown on different sites and blended together in the winery. Once you get past all the growing troubles and issues in the winery (many clones have poor color stability and can create very odd aromas when vinified), the wine that you get tends to be fairly light in color and very high and acidity and tannin. In short, it is the polar opposite of the kind of wine that is very much in fashion right now in that it's not very accessible in its youth and tends to demand food. Needless to say, Xinomavro is facing several uphill battles in the world marketplace.

But is it all worth it? I was able to sample two different bottlings from the same producer in order to find that out. The first wine I tried was the basic Boutari Naoussa bottling. I picked up a bottle of the 2007 vintage for around $18. The wine had a light ruby color in the glass and and a generous nose of crushed red berries, stewed cherries, rich raspberry and some redcurrant with kind of a leafy, herbal edge. There was kind of a chocolate note in it too, like a chocolate covered dried cherry. The texture was a little thin and the wine had a very high acidity and very grippy tannins. I've seen a lot of comparisons between Xinomavro and Pinot Noir, but I definitely agree more with Konstantinos Lazarakis (in his The Wines of Greece) in that I think the more appropriate comparison is with Nebbiolo based wines from the Piedmont. This wine demands food (think meats and pretty much anything you'd serve with a Barolo) and has the structure to age for awhile yet.

The second wine I tried was also from Boutari, but it was their Grand Reserve bottling. I grabbed the 2003 vintage of this for about $40. The Grand Reserve level from Boutari are held for a few years before they are released. They see two years in oak barrels that are a little larger than the barriques used in most of the world (those hold about 225 liters while the ones at Boutari are either 400 or 500 liter barrels), half of which are new oak and the other half neutral oak. They are aged an additional two years in bottle. In the glass, this was a very pale violet color with little saturation. The nose had a spicy, woody kind of aroma with redcurrant, stewed tomatoes, crushed sage, tobacco and old leather. The wine was medium bodied with high acid and high tannins (again, this is a food wine and not an afternoon sipper). The fruits were faded pretty badly from this with just a vague sense of raspberryish red fruit along with dried sage and something a little floral. Though the nose was more interesting and complex on this wine, the palate was not as generous as the entry level Naoussa wine and I don't know if it was in a dumb phase or whether this was just an off-year (Greek wine vintage charts aren't very common). It's not that it was a bad wine, but for the money I'd much rather drink the entry level Naoussa bottling rather than run the risk of a bad vintage of the Grand Reserve, especially since Xinomavro is so finicky in the vineyard and very susceptible to vintage variations. These Grand Reserve bottlings are famously long-lived (from good years, anyway) so I'd like to have a chance to taste one with about 10 years of age on it and see how it's doing at that point. In the meantime, if you're in the mood for something Barolo-like but don't want to fork over Barolo bucks, give Xinomavro a shot.

Monday, May 9, 2011

Bobal - Utiel-Requena, Spain

Pop quiz: what are the top three grapes in Spain by vineyard area planted? No points if you guessed Tempranillo, which is actually second in this race. One bonus point if you knew the little trivia bit about Airén being the most planted grape variety in the world by vineyard acreage (and thus the most planted grape in Spain). You might guess that Garnacha Tinta, Carignan (Mazuelo) or Viura (Macabeo) may take the number three slot, but you'd be mistaken. Bobal covers more than 90,000 ha of land in Spain, accounting for 8% of all plantings, and that means that it is the third most planted grape by acreage in Spain. So why haven't we heard more about Bobal and why is it so difficult to find? I've been wine shopping for this blog for a long time at a variety of stores and to date have found exactly one bottling of Bobal on the shelves. What's going on here?

Well, one explanation is that vineyard area sizes are misleading when we're talking about Spain. As mentioned in the post on Verdejo, it gets really hot in Spain and is very dry in a lot of places. This is especially true of Utiel-Requena, just west of Valencia, where most of Spain's Bobal is grown (it accounts for somewhere between 75 - 90% of vineyard area there). Drought is a problem here so vines are planted pretty far apart so they won't compete with one another for the little rain that they get. The spacing also allows for air circulation between the vines which helps to keep them cool (these vineyards are also at a slight elevation, averaging about 720m above sea level, which helps, but not a lot). But even if we take planting density into account, there's still 90,000 acres of this grape in Spain, which is an awful lot of land. That's more than Garnacha, Carignan or Monastrell which can be found pretty easily in your local wines shops, and it's a lot more than Mencía or Godello, which aren't exactly widespread but can be found with a little diligent looking. So why no Bobal?

The answer is similar to the answer you'd get if you really looked into why you don't see much Colombard from California. In volume of grapes crushed, Colombard is #2 for white grapes in California, yet you almost never see a varietal Colombard. The reason is bulk wine production. Almost all of the Colombard in California is used in bulk and jug wine production, and for many years, most of the Bobal grown in Spain was meeting the same fate as it has never been considered a star variety (Bobal is not mentioned at all in the Far From Ordinary Spanish Wine guide written by Doug Frost and published by the Spanish Institute for Foreign Trade). The red varieties recommended by the Consejo Regulador in Utiel-Requena are Garnacha and Tempranillo while Bobal is relegated to "permitted variety" status. It does make a very good rosado (rosé) wine and is the only permitted grape in the rosado Superior bottlings though it is not permitted in the red Superior wines (Superior wines have a slightly higher alcohol content than the regular wines which is a sign of riper grapes and, theoretically, higher quality wine).

It is native to Utiel-Requena, where it has adapted quite well to the extreme climate of the region (which, I'm guessing, make the land not so great for other forms of agriculture as well). Frosts are a major hazard here and they can persist well into April and May. Bobal buds late, though, and so avoids most of the dangerous frosts. It thrives in the heat, which is good because temperatures can soar to well over 100 degrees in the summer in Valencia. Bobal is also a very vigorous vine which is a quality that all bulk wine growers look for, especially in a region with very low planting density, since they can get a lot more juice from a fewer number of vines. There is a method used in the production of many of these bulk wines called doble pasta. When Bobal is made into a rosado wine, it is left in contact with the skins for only about 12 hours or so. The wine is then drained off the skins and taken to ferment in a different vessel. The grape skins are left behind and a new batch of grape must is poured on top of it so that the new juice is essentially fermenting on two batches of skins. This creates a powerful dark wine with very high alcohol which is used in bulk blending to add color and body to wines from elsewhere that may be overcropped or dilute.

As in so many regions in the world today, there is a newfound commitment to quality on the part of many producers who are trying to elevate Utiel-Requena and Bobal to new heights. Vera des Estenas is one of the oldest producers in this region and they are one of the producers leading the charge for a new Utiel-Requena. They grow several different grapes on this property (including many of the international varieties), but they also have some choice 100+ year old Bobal vines that they make into a high-end bottling called Casa Don Angel which retails for around $30. I was able to pick up a bottle of their 2009 P.G. Bobal (their entry level bottling) for around $11 at Bin Ends. In the glass, the wine was a purple-ruby color with good, intense saturation. The nose was all ripe purple fruits with blueberries, blackberries and something a little flowery. The wine was pretty full-bodied with nice acidity and firm grippy tannins. There was blueberry and blackcurrant fruit with some blackberry jam and a smoky charcoal element to it. This was an interesting wine as it had a lot of really ripe, concentrated fruit, but structurally it was pretty rustic with chunky tannins and nice acidity. It has definitely seen some oak, as the phrase "Madurado en Barrica" practically screams at you from the top of the label. This is a food wine in every sense and would be a great wine to have with grilled meats or something with a good char on it. This is really an excellent bottle of wine for $11 and is a pretty exciting find for me. I will definitely seek out more wines made from this grape and this region because if they're even close to the quality here, they represent one of the great wine values in the world right now.

**UPDATE**

Recently I was able to find and try a rosado version of Bobal. It was the 2010 Vera de Estenas PG Bobal, as in the red wine above, that I was able to find from my friends at Curtis Liquors for about $13. In the glass, the wine was a light ruby color that was fairly deep for a rosé, and looked more like a pale red wine than a pink one. The nose was very aromatic with strawberry, watermelon candy and flower aromas. On the palate, the wine was on the lighter side of medium with fairly high acidity. There were flavors of juicy watermelon and light strawberry with some red cherry flavors as well. The wine was very fruity, juicy and fresh. It was a little tart, but not enough to really be distracting. This is exactly the kind of rosé that I look for in the summer as it was very refreshing and while it wasn't all that complex, it was pure and delicious. If you're a fan of fruit-forward, juicy rosé wines that are popping with red fruit flavors, then you've probably just found your next summer companion, especially at only $13 per bottle.