When I'm out shopping for unusual wines for this website, there are a few sections of most wine shops that I linger in, and a few sections that I blow right through. I usually blow through the South American section, for example, because for the most part, I know exactly what I'm going to find there. The South American sections of nearly every wine shop on earth are laid out the same way with the same kinds of wines in them and I know that the likelihood of me finding something unusual is pretty slim. I tend to linger a little longer in the Italian sections of most shops and really pay attention to what they have because the chances of my finding something unusual in the Italian section are much higher than they are for pretty much any other section in the store.

Some of the larger shops have their Italian sections broken up into smaller, region-specific sections as well, and there are some parts of Italy that I really linger over and some parts that I blow right by. I really dive in to the sections devoted to the wines of Piedmont (or anywhere in northern Italy, really) and Sicily in particular, but the region that I find that I skip over the most is Tuscany. It's certainly not because I don't love wines from this region, it's just that for the most part, Tuscany's wines are very mainstream and the grapes that they use for nearly all of the wines are very well known. I've been dying to try a wine made mostly from some of the supporting players in Chianti like Colorino or Canaiolo, but so far haven't had any luck in finding one. The DOC reds are almost all made from Sangiovese of one form or another while the IGT wines are nearly all some blend of Sangiovese, Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot. I am a big fan of these wines at my dinner table, but for the purposes of this website, Tuscany doesn't provide me with a lot of material. To date, I've only written about one wine from Tuscany, a Teroldego/Syrah blend that was very nice, but which has proven to be an extreme outlier in the world of Tuscan wine.

Which is too bad, because it turns out that there are a lot of grapes that are native to Tuscany that may be of some interest to the wine world. In the 1980's, a group of researchers got together with the aim of identifying and preserving what was left of the native grape population throughout Tuscany in an attempt to stave off the selective extinction of a large number of heirloom grape varieties. They visited 500 estates throughout Tuscany and identified 229 different grapes that were growing throughout the region. They took samples and planted 18 vines of each of them in an experimental vineyard property owned by the San Felice winery called "Vitiarium." A large number of the vines produced grapes that were of no commercial or viticultural interest, but a few of them showed some potential. In 1990 the researchers selected 13 of the most interesting vines and made small lots of wine from the grapes produced at Vitiarium. Of those 13, a grape called Pugnitello quickly established itself as the star of the show, and the San Felice winery planted 1000 cuttings of the vine for more large-scale experimentation. The first commercial bottlings were made in 2003 and have been made each year except for 2005. In many cases, the governmental authorities are slow to recognize new discoveries like Pugnitello, but in 2002, the Italian Ministry of Agriculture put Pugnitello in the National Registry of Vine Varieties, and in 2003 the Tuscan Regional Commission approved Pugnitello for use throughout the region. As of today, only a few wineries other than San Felice are making a varietal Pugnitello, but it is happening.

The original Pugnitello vine had been found in a vineyard near the town of Cinigiano, which is just southwest of Montalcino in Tuscany. The owner of the vineyard site had no information about the grape itself and there doesn't appear to be any record of the grape in any previous ampelographical work. The name Pugnitello was given to the grape because the clusters resemble little balled up fists (pugno, in Italian). The researchers conducted DNA testing on the grape and have thus far found no genetic links to any other existing grape varieties. It's easy to imagine how the grape could have been overlooked in the past. From a grower's perspective, it doesn't have much to recommend it. The clusters are very small and the berries themselves are on the smallish side with thick skins. The vine is also a naturally low-yielder, so pretty much any way you look at it, it doesn't look like a very profitable vine to grow.

Except for the fact that it makes really interesting wine. On the consumer end of things, we often think that this should really be the only consideration given when one decides to plant and tend to the vine, but in reality, good wine is not always profitable for the grower, and it's all too easy to see how over time growers would abandon low-yielding, unreliable vines that make excellent wine for higher yielding varieties that make an inferior product, but make more of it and make it more reliably. Those of us interested in characterful, interesting, different kinds of wines owe a great debt to growers and researchers who are committed to discovering and maintaining the great diversity of vines, whether their efforts pay off with a discovery like Pugnitello or not. The world could very easily shift over to the major ten or so major grape varieties tomorrow without too much gnashing of teeth from the wine drinkers of the world, but part of what I really love about wine is its variety and the seemingly inexhaustible supply of grapes as source material. I am grateful when I hear about discoveries like Pugnitello because I'm certain that the discovery won't lead to any kind of major financial windfall for its discoverers, but the fact that they were curious enough to go out and find something like Pugnitello and make wine from it just so that they could see what might happen really excites me.

I mentioned yesterday that my friend Joe Godas over at Curtis Liquors in Weymouth invited me to his back room to sample a Mavrotragano from Santorini, Greece, he had been given. As he mentions in the comments to that post, his disappointment was as great as mine was at how the Mavrotragano turned out, but little did I know that he had a backup plan. Joe hadn't told me about the Pugnitello before I showed up, but given the Mavrotragano's poor showing, he was gracious enough to open a bottle of the 2006 San Felice Pugnitello da San Felice that he had also been given as a sample bottle. I'm not sure about the SRP, but online prices for this wine seem to be somewhere between $36 and $60. In the glass, the wine was a deep purple ruby color with a medium purple-crimson rim. The nose was somewhat reserved with savory leathery funk over a bit of red cherry fruit. As the wine opened up a bit, some darker, blacker fruits started to show up as well. On the palate, the wine was medium bodied with fairly high acidity and medium tannins. There were ripe cherry fruit flavors with a bit of blackberry, leather, cocoa and espresso. The wine walked the line between dark, ripe fruits and savory, earthy flavors extraordinarily well. It was a bit closer to Brunello than Chianti in style, but really walked the line between the two nicely. This is a very very good wine and it was universally preferred amongst the local distributor's and customer's in Joe's back room to the flashier, oakier Mavrotragano that had preceded it. Yes, this wine sees some new oak, but it's much more integrated here and it gives the grape a chance to express itself in the glass. If you run across this rarity, I'd definitely recommend it to you not only for the great story, but also for the great wine you'll find in your glass.

Wednesday, December 21, 2011

Tuesday, December 20, 2011

Mavrotragano - Santorini, Greece

It doesn't happen all that often, but it does occasionally happen that I will get an invitation from someone familiar with this site to sample an interesting bottle of wine that I wouldn't ordinarily have access to. In today's case, what happened was that Joe Godas, the head wine guy over at Curtis Liquors in Weymouth, received a sample bottle of a wine made from the Mavrotragano grape that he invited me to his shop to try out.

Mavrotragano has been on my radar since I picked up a few bottles of wine made from the Mandilaria grape on the island of Santorini in Greece. In doing the research for those wines, I came across the following passage in Konstantinos Lazarakis' excellent book, The Wines of Greece: "...in terms of quality, it [Mandilaria] is totally eclipsed by the much rarer Mavrotragano...[which] can be Greece's answer to Mourvedre." I rather enjoyed the Mandilaria that I was able to try, so I was very intrigued by the notion that the little blending partner in the wines I had may be the real star. I tried to track down a bottle made mostly from Mavrotragano grapes, but it turns out that very few bottles are actually made and not very much of it finds its way to US shores. The producer for the bottle that I was able to try only makes about 500 cases per year, just to give you an idea.

And, frankly, it's something of a miracle that even that much is made today. Nearly a century ago, Mavrotragano was relatively common throughout the island of Santorini, but what was grown was typically used to make a sweet red wine for the growers themselves that generally wasn't bottled or sold to the public. Through the years, a handful of circumstances began to line up that nearly sounded the death knell for the grape. First of all, Santorini is an absolutely gorgeous place and as the island began to develop something of a reputation amongst tourists, new places for the tourists to stay needed to be built. Many vineyards were torn up to make way for the hotel building blitz undertaken to keep pace with Santorini's rise in stature as a tourist destination.

This was a problem, but there were still plenty of vineyards around Santorini where Mavrotragano could have been planted. The trouble was compounded, though, by the belief that Santorini was not an appropriate place to try and make red wine due to its somewhat erratic climate and the incredibly powerful winds that tear across the island's surface. Historically, the island has been best known for its white wines made from the Assyrtiko grape, and its reputation in the wider wine world has been rising rapidly over the past few decades on the strength of the wines made from that grape (it doesn't hurt anything that it's usually pretty hot on Santorini and the white wines made from Assyrtiko are very refreshing, much more so than a red wine would be, and a major market for the wines made here are the tourists looking more to unwind than to explore the island's vinous range). Further, Assyrtiko is easier to grow in the difficult conditions on Santorini than Mavrotragano, and many growers uprooted their Mavrotragano plantings for new Assyrtiko plantings in greater and greater numbers through the years until Mavrotragano occupied less than 2% of the vineyard land by the year 2000.

As happens in so many places, though, there were a certain number of growers whose curiosity and experimental spirit wouldn't allow them to be content with the one-dimensional view of Santorini wine that had begun to take hold. A few of them looked to the native red grapes that they had on the island and saw that Mavrotragano might have some potential. There were some experimental trials run in the late 1990's that began to show promise, and a few estates began to plant over small vineyard sites to the Mavrotragano grape. Production is still small, but there is a buzz growing about these wines in the international community that seems to indicate that Santorini may have found a red star to complement its already famous Assyrtiko.

As mentioned above, the wine that I was able to try was a sample bottle. I tasted the wine with Joe and a few other locals in a back room at Curtis Liquors following a public tasting of some Italian wines that the shop had put on. The wine was from the 2008 vintage and was from the Domaine Sigalas, who apparently has about 8 hectares of land devoted to the Mavrotragano grape. I'm not entirely sure what the SRP is for this bottle, though Decanter has it listed at £12 in the UK market. In the glass, the wine was a deep crimson ruby color that was opaque in the center to a narrow crimson rim. The nose was nicely aromatic with spicy blueberry, blackberry, black cherry and boysenberry fruits with a touch of smoke to them. The nose was very deep with a lot of interesting fruit aromas. On the palate, the wine was on the fuller side of medium with medium acid and medium tannins. The flavors were very ripe with rich black and blue fruit flavors throughout. There were flavors of blueberry pie, black cherry and blackberry with some baking spice and chocolate and a touch of black pepper. The oak influence was incredibly pronounced here, and the back label confirmed what a lot of us in the room were picking up on. The wine spends 18 months in new oak, and it wears it very loudly. The wine wasn't necessarily bad, but I know that I was somewhat disappointed that so much oak was applied to the wine, as it really masked what might exist for varietal character or any real sense of place. Instead, the wine came across as most similar to a California Zinfandel or an Aussie Shiraz, an overripe fruit bomb (14% abv for those interested) slathered in new oak that can be enjoyable in its own way, but which is interchangeable with any number of other bottles. Oak tastes like oak no matter what and it's disturbing to see something so rare hidden behind all that make-up.

Mavrotragano has been on my radar since I picked up a few bottles of wine made from the Mandilaria grape on the island of Santorini in Greece. In doing the research for those wines, I came across the following passage in Konstantinos Lazarakis' excellent book, The Wines of Greece: "...in terms of quality, it [Mandilaria] is totally eclipsed by the much rarer Mavrotragano...[which] can be Greece's answer to Mourvedre." I rather enjoyed the Mandilaria that I was able to try, so I was very intrigued by the notion that the little blending partner in the wines I had may be the real star. I tried to track down a bottle made mostly from Mavrotragano grapes, but it turns out that very few bottles are actually made and not very much of it finds its way to US shores. The producer for the bottle that I was able to try only makes about 500 cases per year, just to give you an idea.

And, frankly, it's something of a miracle that even that much is made today. Nearly a century ago, Mavrotragano was relatively common throughout the island of Santorini, but what was grown was typically used to make a sweet red wine for the growers themselves that generally wasn't bottled or sold to the public. Through the years, a handful of circumstances began to line up that nearly sounded the death knell for the grape. First of all, Santorini is an absolutely gorgeous place and as the island began to develop something of a reputation amongst tourists, new places for the tourists to stay needed to be built. Many vineyards were torn up to make way for the hotel building blitz undertaken to keep pace with Santorini's rise in stature as a tourist destination.

This was a problem, but there were still plenty of vineyards around Santorini where Mavrotragano could have been planted. The trouble was compounded, though, by the belief that Santorini was not an appropriate place to try and make red wine due to its somewhat erratic climate and the incredibly powerful winds that tear across the island's surface. Historically, the island has been best known for its white wines made from the Assyrtiko grape, and its reputation in the wider wine world has been rising rapidly over the past few decades on the strength of the wines made from that grape (it doesn't hurt anything that it's usually pretty hot on Santorini and the white wines made from Assyrtiko are very refreshing, much more so than a red wine would be, and a major market for the wines made here are the tourists looking more to unwind than to explore the island's vinous range). Further, Assyrtiko is easier to grow in the difficult conditions on Santorini than Mavrotragano, and many growers uprooted their Mavrotragano plantings for new Assyrtiko plantings in greater and greater numbers through the years until Mavrotragano occupied less than 2% of the vineyard land by the year 2000.

As happens in so many places, though, there were a certain number of growers whose curiosity and experimental spirit wouldn't allow them to be content with the one-dimensional view of Santorini wine that had begun to take hold. A few of them looked to the native red grapes that they had on the island and saw that Mavrotragano might have some potential. There were some experimental trials run in the late 1990's that began to show promise, and a few estates began to plant over small vineyard sites to the Mavrotragano grape. Production is still small, but there is a buzz growing about these wines in the international community that seems to indicate that Santorini may have found a red star to complement its already famous Assyrtiko.

As mentioned above, the wine that I was able to try was a sample bottle. I tasted the wine with Joe and a few other locals in a back room at Curtis Liquors following a public tasting of some Italian wines that the shop had put on. The wine was from the 2008 vintage and was from the Domaine Sigalas, who apparently has about 8 hectares of land devoted to the Mavrotragano grape. I'm not entirely sure what the SRP is for this bottle, though Decanter has it listed at £12 in the UK market. In the glass, the wine was a deep crimson ruby color that was opaque in the center to a narrow crimson rim. The nose was nicely aromatic with spicy blueberry, blackberry, black cherry and boysenberry fruits with a touch of smoke to them. The nose was very deep with a lot of interesting fruit aromas. On the palate, the wine was on the fuller side of medium with medium acid and medium tannins. The flavors were very ripe with rich black and blue fruit flavors throughout. There were flavors of blueberry pie, black cherry and blackberry with some baking spice and chocolate and a touch of black pepper. The oak influence was incredibly pronounced here, and the back label confirmed what a lot of us in the room were picking up on. The wine spends 18 months in new oak, and it wears it very loudly. The wine wasn't necessarily bad, but I know that I was somewhat disappointed that so much oak was applied to the wine, as it really masked what might exist for varietal character or any real sense of place. Instead, the wine came across as most similar to a California Zinfandel or an Aussie Shiraz, an overripe fruit bomb (14% abv for those interested) slathered in new oak that can be enjoyable in its own way, but which is interchangeable with any number of other bottles. Oak tastes like oak no matter what and it's disturbing to see something so rare hidden behind all that make-up.

Wednesday, December 14, 2011

Southwest France Round-Up - Virtual Tasting of 12/7/11

Last Wednesday night I was invited to a virtual tasting of eight wines from all over Southwest France. The tasting was led by Master Sommelier and spokesperson for the South West Wines of France Council Fred Dexheimer, who led a group of bloggers through the eight wines that were provided to us free of charge. Today I'd like to give my impressions of the eight wines we tasted, some of which we've covered here before and some of which we'll get to shortly.

The total vineyard area for Southwest France is about 50,000 hectares, half of which are in the hands of private producers and half of which is used by members of local co-ops. The region produces about 450 million bottles of wine annually, split pretty evenly between white wines on one hand and red and rosé wines on the other. There's also a small percentage of sparkling wine here made in the very old (older than the Champagne method) methode ancestrale which we took a brief look at when we looked at a wine made from the Mauzac grape. I've written fairly extensively about the local wine histories of the subregions of Gaillac, Marcillac, Jurançon and Fronton elsewhere on the site, so I won't go over all that again. Instead, I'm just going to jump right in and go through the wines in the order they were presented to us.

The first wine was the 2010 Producteurs Plaimont "Colombelle" Blanc from the Côtes de Gascogne, which is just south of Bordeaux in the Armagnac region of France. The blend here is 80% Colombard and 20% Sauvignon Blanc and Ugni Blanc and the SRP is $10. In the glass, the wine was a pale silvery lemon color. The nose was very aromatic with white grapefruit and grapefruit peel with a bit of pear fruit as well. There was also a very prominent kind of grassy herbaceousness that reminded me a lot of Sauvignon Blanc. On the palate, the wine was light bodied with high acidity. There were flavors of tart lemon, white grapefruit and sour pineapple. The grassy herbaceous character extended through the palate as well. The wine was clean and very refreshing with a stony minerality to the finish. This wine would be a great stand-in for those looking for a substitute for Sauvignon Blanc or anyone looking for a tart, high acid aperitif. Surprisingly, this wine held up very well the next day, and even tasted a little better as the acid had calmed down a bit. For $10, this is an outstanding wine that would be great with shellfish or light chicken dishes.

The second wine we tried was from the same vintage and producer, but was a red wine (called Colombelle Rouge) that was about 60% Tannat, 20% Merlot and 20% Cabernet Sauvignon with an SRP of $10. Tannat is usually a very fierce grape in its youth, so to soften it, the winemakers used a technique known as micro-oxygenation, which is essentially like sticking an aquarium bubbler into the wine as it is fermenting to introduce a lot of oxygen very quickly which reduces the tannic bite of a wine and makes it more approachable in its youth. The technique is not without controversy, but you can go watch Mondovino or read any number of other writers if you're interested. In the glass, this wine was a medium purple ruby color which wasn't all that deep, but which was very intense. The nose was nicely aromatic with black cherry and dark plummy fruit with a noticeable bell pepper edge to it. On the palate, the wine was medium bodied with fairly high acidity and low tannins. There was juicy cherryish fruit with some bell pepper herbaceousness and some dark, earthy undertones to balance it out. Overall, it was a little thin and hollow for my tastes, but it represents a pretty decent value for the money. It had completely fallen apart by day two and, overall, it was my least favorite wine of the tasting.

For the third wine, we went back to the whites and had a 2008 Château Montus Blanc that was from the Pacherenc du Vic-Bilh, which is the name for white wines made in the Madiran region. The wine is made up of 90% Petit Courbu and 10% Petit Manseng with an SRP of $27. The wine is aged on the lees in very large (600 gallon) new French Oak barrels for between 6-8 months before bottling. In the glass, the wine had a deep golden straw color. The nose was nicely aromatic with vanilla, butterscotch and baked apple aromas with some pear, pineapple and pastry crust. On the palate, the wine was just on the fuller side of medium with fairly high acidity. There were flavors of lemony citrus, ripe apple and tropical pineapple flavors with side notes of pastry dough, butter and vanilla. I am usually not a fan of oak in white wines, but the oak is integrated beautifully here and the wine is exceptionally balanced. It's very similar to a fine white Burgundy and would pair with essentially the same kinds of dishes. This wine suffered a bit on day two, but it was one of only two of the bottles that I completely finished and it was the second best wine of the tasting in my opinion. $27 is a little high, but the quality is exceptional here and I wouldn't hesitate to pay full retail for this wine should I run across it again.

The fourth wine was one that I've had before and one I've written about here. The wine was the 2010 Domaine du Cros "Lo Sang del Pais" made from the Fer Servadou grape (100%) in the Marcillac region. The SRP for this bottle is around $12. In the glass, the wine was a deep, nearly opaque purple-ruby color. The nose was nicely aromatic with waxy black cherry and brambly blackberry fruit with some vegetal, smoky bell pepper aromas. On the palate, the wine was medium bodied with fairly high acidity and medium tannins. There were flavors of dark black fruits like blackberry and black cherry with a lot of smoke and savory meat flavors as well. The tasting note provided to us says that the wine "displays the iron mineral character that is characteristic of the terroir," and I can kind of see that, I guess. There was a bitter, metallic tang to the finish of the wine that reminded me of the unfortunate occasions in my life when I've had a bit of rusty metal in my mouth. Iron oxide does have a particular tang to it, and I could certainly see it here, though I'm not totally sure if it was a good thing or not. I wasn't a bit fan of this wine the first time I had it, and I'm still not totally sold on it, but for $12, it's definitely worth a shot for those curious about Fer Servadou. The wine held up pretty well by day two, but there were other wines that I was more interested in within this tasting.

The fifth wine we tasted was the 2008 Domaine des Terrisses Gaillac Rouge which was 50% Fer Servadou, 30% Duras and 20% Syrah. The SRP for this wine is $13. In the glass, the wine was a very deep, purple ruby color that was inky black in the center all the way out to a very narrow violet rim. The nose was a bit reserved with some smoky black fruit and a little bit of bell pepper herbaceousness. On the palate, the wine was on the fuller side of medium with medium acidity and fairly high tannins. There were flavors of dark black cherry and blackberry fruit with an intense smokiness and bitter iron tang on the finish. There was also a touch of black pepper that lingered on the finish. The wine was dark, brooding and a bit backward, needing a bit of time to really open up, which was a little surprising to me since our notes say that the wine is matured in stainless steel instead of wood. Perhaps the lack of oxidative aging kept it tightly wound, but I'm not sure. It was one of the few wines that was much better the second day. I certainly enjoyed it, but I was much more fond of the Domaine Philémon Gaillac Rouge I wrote about in my Fer post, which is available at the same price point. This wine will probably improve with some extra time in the bottle so if you run across it, maybe give it a little time before cracking it open.

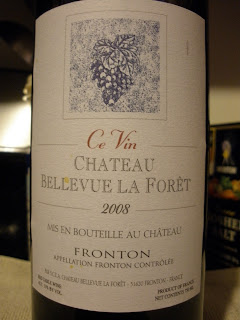

The sixth wine that we tried was the 2008 Chateau Bellevue La Forêt "Ce Vin," made from the Négrette grape in the Fronton region of France. I wrote about Négrette yesterday and also wrote about this wine, so those interested in reading more about the grape can do so here, and I'll just cut and paste my tasting note from yesterday's post. In the glass, the wine was a deep, inky purple-ruby color. The nose was very aromatic with strawberry and red berry fruit with a floral, rosy kind of character to it. The nose was intoxicating and reminded me a bit of the Frappato that I wrote about a few months ago. On the palate the wine was medium bodied with medium acidity and low tannins. Like the other Fronton above, the palate was a bit of letdown from the nose, as this wine had some raspberry and blackberry fruit with a touch of bitter smoke and spice. Overall, it was a little hollow and thin and the bitterness was a little too pronounced for me. I tasted all of the wines for the tasting the next day and this one had suffered the most, completely falling apart by day two.

The seventh wine we had was the 2005 Clos Fardet Cuvée Moutoue Fardet which was made from 98% Tannat and 2% Cabernet Franc. The wine is from the Madiran region and has an SRP of about $27. The wine is made with natural yeast and minimal sulfur contact and is aged in 400 liter barrels for five years before being bottled. In the glass, the wine had a deep, inky purple-black color that was opaque out to a narrow crimson rim. The nose was very aromatic with tobacco, spice box, leather, cocoa, rich black cherry, blackberry and black plum fruit and just a hint of mint. The nose was deep, complex and compelling and it was a struggle to get past the sniffing phase of the tasting. On the palate, the wine was full bodied with fairly high acidity and fairly high tannins. The flavor profile was deep, dense and ripe with boysenberry, blackberry and black cherry fruit with deep earthy chocolate, baking spice and cigar tobacco flavors as well. It was incredibly powerful and layered but also exceptionally balanced. It was the hands down superstar of the tasting for me and was drinking well three days after I opened it. At $27, this wine is a steal and I wouldn't hesitate to pay double that retail if I had to. The big problem is that they only make about 350 cases total, about half of which makes it to US shores. It is a phenomenal wine that is now on my personal "buy on sight" list.

The final wine that we tried was the 2008 Domaine Brana "Ohtiza" Rouge from the very hilly Irouléguy region of France, right on the Spanish border. The wine is made up of 80% Tannat and 20% Cabernet Franc and retails for about $26. In the glass the wine was a deep purple-ruby color that was nearly opaque out to a narrow violet rim. The nose was nicely aromatic with blackberry and black cherry fruit with a touch of smoke. It turns out that I'm very sensitive to bell pepper aromas, and I picked up quite a bit on this wine. On the palate the wine was on the fuller side of medium with fairly high acid and medium tannins. There were flavors of tart cherry and under-ripe blackberry fruits with something a little cranberryish about it. The wine was very lean and angular with sour berry fruits and vegetal flavors. Where the Madiran was all soft curves and plush fruits, this wine was sharp and sour and wasn't as much to my taste. It held up fairly well by day two, but never really got any softer. Perhaps more so than any other wine in the tasting, this wine really needed some food and I wasn't really able to accommodate it properly. This would be really good with sausage stuffed peppers or really any rich red meat dish with a heavy vegetable presence.

Overall, the tasting was exceptionally well done and I had a great time participating. There was a wonderful range of wines represented from a wide variety of regions within Southwest France. I came away from this tasting even more convinced that Southwest France is one of the great world wine regions for very good wines made from unusual grapes at great prices.

Just to reiterate, all wines reviewed above were provided to me free of charge and I have done my best to review them as objectively as I could. I received no compensation for participating in this event other than the wines.

The total vineyard area for Southwest France is about 50,000 hectares, half of which are in the hands of private producers and half of which is used by members of local co-ops. The region produces about 450 million bottles of wine annually, split pretty evenly between white wines on one hand and red and rosé wines on the other. There's also a small percentage of sparkling wine here made in the very old (older than the Champagne method) methode ancestrale which we took a brief look at when we looked at a wine made from the Mauzac grape. I've written fairly extensively about the local wine histories of the subregions of Gaillac, Marcillac, Jurançon and Fronton elsewhere on the site, so I won't go over all that again. Instead, I'm just going to jump right in and go through the wines in the order they were presented to us.

The first wine was the 2010 Producteurs Plaimont "Colombelle" Blanc from the Côtes de Gascogne, which is just south of Bordeaux in the Armagnac region of France. The blend here is 80% Colombard and 20% Sauvignon Blanc and Ugni Blanc and the SRP is $10. In the glass, the wine was a pale silvery lemon color. The nose was very aromatic with white grapefruit and grapefruit peel with a bit of pear fruit as well. There was also a very prominent kind of grassy herbaceousness that reminded me a lot of Sauvignon Blanc. On the palate, the wine was light bodied with high acidity. There were flavors of tart lemon, white grapefruit and sour pineapple. The grassy herbaceous character extended through the palate as well. The wine was clean and very refreshing with a stony minerality to the finish. This wine would be a great stand-in for those looking for a substitute for Sauvignon Blanc or anyone looking for a tart, high acid aperitif. Surprisingly, this wine held up very well the next day, and even tasted a little better as the acid had calmed down a bit. For $10, this is an outstanding wine that would be great with shellfish or light chicken dishes.

The second wine we tried was from the same vintage and producer, but was a red wine (called Colombelle Rouge) that was about 60% Tannat, 20% Merlot and 20% Cabernet Sauvignon with an SRP of $10. Tannat is usually a very fierce grape in its youth, so to soften it, the winemakers used a technique known as micro-oxygenation, which is essentially like sticking an aquarium bubbler into the wine as it is fermenting to introduce a lot of oxygen very quickly which reduces the tannic bite of a wine and makes it more approachable in its youth. The technique is not without controversy, but you can go watch Mondovino or read any number of other writers if you're interested. In the glass, this wine was a medium purple ruby color which wasn't all that deep, but which was very intense. The nose was nicely aromatic with black cherry and dark plummy fruit with a noticeable bell pepper edge to it. On the palate, the wine was medium bodied with fairly high acidity and low tannins. There was juicy cherryish fruit with some bell pepper herbaceousness and some dark, earthy undertones to balance it out. Overall, it was a little thin and hollow for my tastes, but it represents a pretty decent value for the money. It had completely fallen apart by day two and, overall, it was my least favorite wine of the tasting.

For the third wine, we went back to the whites and had a 2008 Château Montus Blanc that was from the Pacherenc du Vic-Bilh, which is the name for white wines made in the Madiran region. The wine is made up of 90% Petit Courbu and 10% Petit Manseng with an SRP of $27. The wine is aged on the lees in very large (600 gallon) new French Oak barrels for between 6-8 months before bottling. In the glass, the wine had a deep golden straw color. The nose was nicely aromatic with vanilla, butterscotch and baked apple aromas with some pear, pineapple and pastry crust. On the palate, the wine was just on the fuller side of medium with fairly high acidity. There were flavors of lemony citrus, ripe apple and tropical pineapple flavors with side notes of pastry dough, butter and vanilla. I am usually not a fan of oak in white wines, but the oak is integrated beautifully here and the wine is exceptionally balanced. It's very similar to a fine white Burgundy and would pair with essentially the same kinds of dishes. This wine suffered a bit on day two, but it was one of only two of the bottles that I completely finished and it was the second best wine of the tasting in my opinion. $27 is a little high, but the quality is exceptional here and I wouldn't hesitate to pay full retail for this wine should I run across it again.

The fourth wine was one that I've had before and one I've written about here. The wine was the 2010 Domaine du Cros "Lo Sang del Pais" made from the Fer Servadou grape (100%) in the Marcillac region. The SRP for this bottle is around $12. In the glass, the wine was a deep, nearly opaque purple-ruby color. The nose was nicely aromatic with waxy black cherry and brambly blackberry fruit with some vegetal, smoky bell pepper aromas. On the palate, the wine was medium bodied with fairly high acidity and medium tannins. There were flavors of dark black fruits like blackberry and black cherry with a lot of smoke and savory meat flavors as well. The tasting note provided to us says that the wine "displays the iron mineral character that is characteristic of the terroir," and I can kind of see that, I guess. There was a bitter, metallic tang to the finish of the wine that reminded me of the unfortunate occasions in my life when I've had a bit of rusty metal in my mouth. Iron oxide does have a particular tang to it, and I could certainly see it here, though I'm not totally sure if it was a good thing or not. I wasn't a bit fan of this wine the first time I had it, and I'm still not totally sold on it, but for $12, it's definitely worth a shot for those curious about Fer Servadou. The wine held up pretty well by day two, but there were other wines that I was more interested in within this tasting.

The fifth wine we tasted was the 2008 Domaine des Terrisses Gaillac Rouge which was 50% Fer Servadou, 30% Duras and 20% Syrah. The SRP for this wine is $13. In the glass, the wine was a very deep, purple ruby color that was inky black in the center all the way out to a very narrow violet rim. The nose was a bit reserved with some smoky black fruit and a little bit of bell pepper herbaceousness. On the palate, the wine was on the fuller side of medium with medium acidity and fairly high tannins. There were flavors of dark black cherry and blackberry fruit with an intense smokiness and bitter iron tang on the finish. There was also a touch of black pepper that lingered on the finish. The wine was dark, brooding and a bit backward, needing a bit of time to really open up, which was a little surprising to me since our notes say that the wine is matured in stainless steel instead of wood. Perhaps the lack of oxidative aging kept it tightly wound, but I'm not sure. It was one of the few wines that was much better the second day. I certainly enjoyed it, but I was much more fond of the Domaine Philémon Gaillac Rouge I wrote about in my Fer post, which is available at the same price point. This wine will probably improve with some extra time in the bottle so if you run across it, maybe give it a little time before cracking it open.

The sixth wine that we tried was the 2008 Chateau Bellevue La Forêt "Ce Vin," made from the Négrette grape in the Fronton region of France. I wrote about Négrette yesterday and also wrote about this wine, so those interested in reading more about the grape can do so here, and I'll just cut and paste my tasting note from yesterday's post. In the glass, the wine was a deep, inky purple-ruby color. The nose was very aromatic with strawberry and red berry fruit with a floral, rosy kind of character to it. The nose was intoxicating and reminded me a bit of the Frappato that I wrote about a few months ago. On the palate the wine was medium bodied with medium acidity and low tannins. Like the other Fronton above, the palate was a bit of letdown from the nose, as this wine had some raspberry and blackberry fruit with a touch of bitter smoke and spice. Overall, it was a little hollow and thin and the bitterness was a little too pronounced for me. I tasted all of the wines for the tasting the next day and this one had suffered the most, completely falling apart by day two.

The seventh wine we had was the 2005 Clos Fardet Cuvée Moutoue Fardet which was made from 98% Tannat and 2% Cabernet Franc. The wine is from the Madiran region and has an SRP of about $27. The wine is made with natural yeast and minimal sulfur contact and is aged in 400 liter barrels for five years before being bottled. In the glass, the wine had a deep, inky purple-black color that was opaque out to a narrow crimson rim. The nose was very aromatic with tobacco, spice box, leather, cocoa, rich black cherry, blackberry and black plum fruit and just a hint of mint. The nose was deep, complex and compelling and it was a struggle to get past the sniffing phase of the tasting. On the palate, the wine was full bodied with fairly high acidity and fairly high tannins. The flavor profile was deep, dense and ripe with boysenberry, blackberry and black cherry fruit with deep earthy chocolate, baking spice and cigar tobacco flavors as well. It was incredibly powerful and layered but also exceptionally balanced. It was the hands down superstar of the tasting for me and was drinking well three days after I opened it. At $27, this wine is a steal and I wouldn't hesitate to pay double that retail if I had to. The big problem is that they only make about 350 cases total, about half of which makes it to US shores. It is a phenomenal wine that is now on my personal "buy on sight" list.

The final wine that we tried was the 2008 Domaine Brana "Ohtiza" Rouge from the very hilly Irouléguy region of France, right on the Spanish border. The wine is made up of 80% Tannat and 20% Cabernet Franc and retails for about $26. In the glass the wine was a deep purple-ruby color that was nearly opaque out to a narrow violet rim. The nose was nicely aromatic with blackberry and black cherry fruit with a touch of smoke. It turns out that I'm very sensitive to bell pepper aromas, and I picked up quite a bit on this wine. On the palate the wine was on the fuller side of medium with fairly high acid and medium tannins. There were flavors of tart cherry and under-ripe blackberry fruits with something a little cranberryish about it. The wine was very lean and angular with sour berry fruits and vegetal flavors. Where the Madiran was all soft curves and plush fruits, this wine was sharp and sour and wasn't as much to my taste. It held up fairly well by day two, but never really got any softer. Perhaps more so than any other wine in the tasting, this wine really needed some food and I wasn't really able to accommodate it properly. This would be really good with sausage stuffed peppers or really any rich red meat dish with a heavy vegetable presence.

Overall, the tasting was exceptionally well done and I had a great time participating. There was a wonderful range of wines represented from a wide variety of regions within Southwest France. I came away from this tasting even more convinced that Southwest France is one of the great world wine regions for very good wines made from unusual grapes at great prices.

Just to reiterate, all wines reviewed above were provided to me free of charge and I have done my best to review them as objectively as I could. I received no compensation for participating in this event other than the wines.

Tuesday, December 13, 2011

Négrette - Fronton, France

We've recently been visiting Southwest France quite a bit around here, having taken a look at the Fer Servadou grape from Gaillac and Marcillac, the Duras grape from Gaillac, and the Gros Manseng grape from the Jurancon region. There are a number of really interesting grapes grown only in Southwest France and today we're going to take a look at yet another of them, the Négrette grape.

Négrette is grown in a few different areas, but Fronton is its best known home. The Côtes du Frontonnais is located just southwest of Gaillac and just north of the city of Toulouse, on the western bank of the Tarn river. The viticultural history of the region can be traced back to Roman times, as the city of Montauban, located just across the Tarn river from Fronton, was an early Roman outpost before they went on to conquer all of Gaul. The fall of Rome resulted in a very turbulent time as many Barbarian tribes invaded the region repeatedly. The mood was so bleak that many of the locals believed that the world was going to come to an end after the first millennium AD. As we all know, the year 1000 came and went without incident, and many of the landholders were so grateful for their continued existence that they donated large tracts of their land to the Catholic Church.

Around the same time, an organization known as the Knights of Saint John came into the region. The Knights were a charitable religious organization who were focused on providing food and shelter for religious pilgrims passing through the area on their way to the Holy City Santiago de Compostela (in western Spain) or on their way to the Holy Land. The Knights were based on the Greek island of Cyprus, and it is said that they brought with them a grape called "Mavro," which means "black" in Greek, which is thought to be a direct ancestor of the modern Négrette grape. Etymologically, this makes a certain sense, as both grapes are clearly named for the dark color of their skins, juice and the resulting wine. It's a good story, but it's probably not true. More recent research indicates that Négrette is probably a member of the côt family which also includes the Southwestern French grapes Malbec and Tannat. This family is thought to have been brought from Spain in the Middle Ages before settling in Southwest France. There's a story that Négrette first came to prominence in Gaillac, but that the locals believed that the grape wasn't worthy of their soils and they banished the grape to Fronton, in much the same way as Gamay was pushed out of the better vineyard sites of Burgundy. It turns out that this a great thing for the grape, as it is very prone to fungal diseases and needs a hot, dry climate such as that found in the Fronton region. There are about 1300 hectares planted throughout France with the overwhelming majority in Fronton. There is also some grown in California where it is known as Pinot St. George, though the grape appears to be unrelated to the Pinot family.

I was fortunate enough to try three different bottles containing Négrette. The first was the 2007 Le Roc "Le Classique" that I picked up from my friends at Curtis Liquors for about $10. The wine is 70% Negrette, 20% Syrah and 10% Cabernet Sauvignon. The AOC regulations stipulate that the Négrette grape must make up 50 - 70% of the acreage of a grower's vineyard area, and that Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet France, Syrah or Gamay should make up no more than 25% of a final blend, while Malbec should only make up 10%. In the glass, the wine was a deep purple-ruby color and was nearly opaque through its core. The nose was very aromatic with funky wild blackberry and black cherry fruit with some wet leather. The aromatics were lifted and powerful and the wine was a real pleasure just to sniff. On the palate, the wine was medium bodied with acid just on the higher side of medium and medium, powdery tannins. There were sour black cherry and blackberry fruit with some espresso and smoke. The finish is a little short with a serious bitter bite on the end, though it spreads out a bit as it opens. It was a disappointing follow-up based on the powerfully aromatic nose, but it was a very good wine, especially at the $10 price point. Red wines from the Négrette grape are meant to be drunk young, and it this one may have been starting to fall apart a bit, but it was still hanging in there.

The second wine I was able to try was the NV Nicolas Gelis "Flambant" Bulles Rouge which I picked up from my friends at the Wine Bottega for about $15. The blend here is about 85% Négrette and 15% Syrah. In the glass, the wine was a deep lavender color with a bit of fizz to it. The nose was very aromatic with blackberry candy and dusky cherry fruit with a savage, damp leaf sort of character to it. On the palate, the wine was medium bodied with medium acid and a light fizz. It was medium sweet and clocked in at only 8% alcohol. It tasted kind of like a blackberry or a black cherry soda. There were a lot of candied black fruits with a touch of wild, wet underbrush to it. It reminded me a lot of Brachetto d'Acqui and had a lot of the candyish kinds of characteristics that I find in good Brachetto. It did have just enough of that savage, foresty character to it so that it wasn't like pure sugar, but it was still very friendly and was a lot of fun to drink.

I recently was asked to take part in a virtual tasting of wines from Southwest France led by Master Sommelier Fred Dexheimer, which I will be writing more about soon, but one of the wines we took a look at was the 2008 Chateau Bellevue La Forêt "Ce Vin," which retails for about $11 a bottle. I received this bottle as a free sample for the purposes of the online seminar. They told us that the wine is 100% Négrette, which is very hard to find. In the glass, the wine was a deep, inky purple-ruby color. The nose was very aromatic with strawberry and red berry fruit with a floral, rosy kind of character to it. The nose was intoxicating and reminded me a bit of the Frappato that I wrote about a few months ago. On the palate the wine was medium bodied with medium acidity and low tannins. Like the other Fronton above, the palate was a bit of letdown from the nose, as this wine had some raspberry and blackberry fruit with a touch of bitter smoke and spice. Overall, it was a little hollow and thin and the bitterness was a little too pronounced for me. I tasted all of the wines for the tasting the next day and this one had suffered the most, completely falling apart by day two. I would have loved to try a Négrette from a more recent vintage, as most sources indicate that these wines deteriorate very rapidly after the vintage, but I've certainly seen enough in these three wines to excited about the possibilities for this grape.

Négrette is grown in a few different areas, but Fronton is its best known home. The Côtes du Frontonnais is located just southwest of Gaillac and just north of the city of Toulouse, on the western bank of the Tarn river. The viticultural history of the region can be traced back to Roman times, as the city of Montauban, located just across the Tarn river from Fronton, was an early Roman outpost before they went on to conquer all of Gaul. The fall of Rome resulted in a very turbulent time as many Barbarian tribes invaded the region repeatedly. The mood was so bleak that many of the locals believed that the world was going to come to an end after the first millennium AD. As we all know, the year 1000 came and went without incident, and many of the landholders were so grateful for their continued existence that they donated large tracts of their land to the Catholic Church.

Around the same time, an organization known as the Knights of Saint John came into the region. The Knights were a charitable religious organization who were focused on providing food and shelter for religious pilgrims passing through the area on their way to the Holy City Santiago de Compostela (in western Spain) or on their way to the Holy Land. The Knights were based on the Greek island of Cyprus, and it is said that they brought with them a grape called "Mavro," which means "black" in Greek, which is thought to be a direct ancestor of the modern Négrette grape. Etymologically, this makes a certain sense, as both grapes are clearly named for the dark color of their skins, juice and the resulting wine. It's a good story, but it's probably not true. More recent research indicates that Négrette is probably a member of the côt family which also includes the Southwestern French grapes Malbec and Tannat. This family is thought to have been brought from Spain in the Middle Ages before settling in Southwest France. There's a story that Négrette first came to prominence in Gaillac, but that the locals believed that the grape wasn't worthy of their soils and they banished the grape to Fronton, in much the same way as Gamay was pushed out of the better vineyard sites of Burgundy. It turns out that this a great thing for the grape, as it is very prone to fungal diseases and needs a hot, dry climate such as that found in the Fronton region. There are about 1300 hectares planted throughout France with the overwhelming majority in Fronton. There is also some grown in California where it is known as Pinot St. George, though the grape appears to be unrelated to the Pinot family.

I was fortunate enough to try three different bottles containing Négrette. The first was the 2007 Le Roc "Le Classique" that I picked up from my friends at Curtis Liquors for about $10. The wine is 70% Negrette, 20% Syrah and 10% Cabernet Sauvignon. The AOC regulations stipulate that the Négrette grape must make up 50 - 70% of the acreage of a grower's vineyard area, and that Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet France, Syrah or Gamay should make up no more than 25% of a final blend, while Malbec should only make up 10%. In the glass, the wine was a deep purple-ruby color and was nearly opaque through its core. The nose was very aromatic with funky wild blackberry and black cherry fruit with some wet leather. The aromatics were lifted and powerful and the wine was a real pleasure just to sniff. On the palate, the wine was medium bodied with acid just on the higher side of medium and medium, powdery tannins. There were sour black cherry and blackberry fruit with some espresso and smoke. The finish is a little short with a serious bitter bite on the end, though it spreads out a bit as it opens. It was a disappointing follow-up based on the powerfully aromatic nose, but it was a very good wine, especially at the $10 price point. Red wines from the Négrette grape are meant to be drunk young, and it this one may have been starting to fall apart a bit, but it was still hanging in there.

The second wine I was able to try was the NV Nicolas Gelis "Flambant" Bulles Rouge which I picked up from my friends at the Wine Bottega for about $15. The blend here is about 85% Négrette and 15% Syrah. In the glass, the wine was a deep lavender color with a bit of fizz to it. The nose was very aromatic with blackberry candy and dusky cherry fruit with a savage, damp leaf sort of character to it. On the palate, the wine was medium bodied with medium acid and a light fizz. It was medium sweet and clocked in at only 8% alcohol. It tasted kind of like a blackberry or a black cherry soda. There were a lot of candied black fruits with a touch of wild, wet underbrush to it. It reminded me a lot of Brachetto d'Acqui and had a lot of the candyish kinds of characteristics that I find in good Brachetto. It did have just enough of that savage, foresty character to it so that it wasn't like pure sugar, but it was still very friendly and was a lot of fun to drink.

I recently was asked to take part in a virtual tasting of wines from Southwest France led by Master Sommelier Fred Dexheimer, which I will be writing more about soon, but one of the wines we took a look at was the 2008 Chateau Bellevue La Forêt "Ce Vin," which retails for about $11 a bottle. I received this bottle as a free sample for the purposes of the online seminar. They told us that the wine is 100% Négrette, which is very hard to find. In the glass, the wine was a deep, inky purple-ruby color. The nose was very aromatic with strawberry and red berry fruit with a floral, rosy kind of character to it. The nose was intoxicating and reminded me a bit of the Frappato that I wrote about a few months ago. On the palate the wine was medium bodied with medium acidity and low tannins. Like the other Fronton above, the palate was a bit of letdown from the nose, as this wine had some raspberry and blackberry fruit with a touch of bitter smoke and spice. Overall, it was a little hollow and thin and the bitterness was a little too pronounced for me. I tasted all of the wines for the tasting the next day and this one had suffered the most, completely falling apart by day two. I would have loved to try a Négrette from a more recent vintage, as most sources indicate that these wines deteriorate very rapidly after the vintage, but I've certainly seen enough in these three wines to excited about the possibilities for this grape.

Wednesday, December 7, 2011

Petite Arvine - Valle d'Aosta, Italy and Vétroz, Switzerland

Today's post is hardest kind of post to write. I've this really cool, rare grape to write about and my research keeps coming up with nothing. Sure, there's a sentence here or there about Petite Arvine, but there isn't all that much of substance. Sometimes I get lucky with these things and find out that there's some kind of controversy or interesting mystery about a grape, but with Petite Arvine, there just doesn't seem to be anything like that. I could, of course, just ignore the grape and move on, but I bought two bottles of this stuff and am going to find some way to make use of them. So, without further ado, here's what I was able to find about Petite Arvine.

Petite Arvine's origins are mysterious, but unfortunately that's all they are. The grape is thought to be native to Switzerland and one source claims that it has been grown in the Valais regions of Switzerland since 1602, while another source dates it to 1878. The 1878 date is important, as it is when the International Ampelographic Society met in Geneva and decided that Petite Arvine was a unique grape not found anywhere else in the Valais or in the world. It is this article that people point to when trying to establish a Swiss origin for the grape, but without knowing exactly how thorough their search was, it's hard to say how credible their statement is. The grape is also known today in the Valle d'Aosta of Italy and some source say that the grape is actually named for the Arve valley around Savoy where the grape is thought to have entered the Valais region, possibly from the Valle d'Aosta. In either case, the grape almost certainly has Alpine origins and today is found virtually nowhere other than the Valais and the Valle d'Aosta.

The grape's parentage is a mystery as well. Petite Arvine was thought to be closely related to Amigne for some time, but recent DNA testing has shown that they may not be that closely related after all. It does seem to be distantly related to Prié Blanc, Premetta and possibly Chasselas. The grape is commonly known as Arvine these days, though the Petite Arvine name was necessary for many years to differentiate it from another grape known as Grosse Arvine (or sometimes Arvine Grande) which has larger berries and which makes wine of a much lower quality. Today, Grosse Arvine is practically extinct (it does not exist in cultivation but only in grape collections) so the distinction isn't as important. The two grapes are related, but not as closely as their names might have you believe. Confusingly, both Arvine and Arvine Grande are synonyms for Silvaner, which is not related to either Petite Arvine or Grosse Arvine.

Viticulturally, Petite Arvine is a very late ripener, sometimes ripening a full month later than Chasselas. As a result, the vine needs a lot of sun to ensure that it gets completely ripe and it also needs to be protected from the wind as the clusters can be fragile. Wines made from the grape are highly esteemed, and though the Oxford Companion to Wine doesn't have much to say about Petite Arvine, it does say that it is "the finest of the grape specialties of Valais." Despite it's high critical esteem, Petite Arvine is not very widely grown, occupying only about 150 hectares of land in Switzerland, though this figure is up significantly from the 65 hectares planted in the year 2000. I couldn't find any numbers on the Italian acreage devoted to the grape, but you can be sure that it is extraordinarily small. Wines made from the grape run the gamut from bone dry to sticky sweet.

I was fortunate enough to find a bottle of Petite Arvine from both Switzerland and Italy. The first bottle I found was the 2007 Romain Papilloud Cave du Vieux Moulin Petite Arvine from the Vétroz region of Switzerland (home to our old friend Amigne). The wine came in a 500 mL bottle and I picked it up for about $39. In the glass, the wine was a fairly deep lemon gold color. The nose was very shy with a little bit of peaches and honey and something a little flowery, but it was mostly a blank and never really opened up. On the palate, the wine was medium bodied with fairly low acidity and was surprisingly dry. Given the size of the bottle, I was expecting something a little sweet, but this wasn't it. There were flavors of honeysuckle flower and under ripe peaches, but it was mostly metallic and hollow tasting. I don't say this very often, but this was an awful bottle of wine. It tasted like chemicals and was just bitter and mean. It was so bad, I was only able to get through one glass and had to pour the rest down the sink, which I almost never do. I don't know if this was just a bad bottle or if this wine always tastes this way, but for $39, I won't be running the experiment twice.

The second bottle that I picked up was the 2005 Grosjean Petite Arvine which I got from my friends at Curtis Liquors for about $30. In the glass the wine was a yellow gold color that was so vibrant it almost had a kind of neon tinge to it. The nose was very aromatic with ripe apple, butterscotch, pineapple tropical fruit, lees and a biscuitty, pastry-like kind of thing going on. On the palate, the wine was on the lighter side of medium with high acidity. There were flavors of ripe apple and pear, pastry dough, and a distinctive leesy, cheesy kind of flavor to it (the wine is fermented and held on its lees, which are stirred, for a month). I thought I was picking up some oak, but this wine is stainless steel fermented, so it was probably just from the lees contact. The wine not all that fleshy, but the flavors seem very decadent and rich. Nearly everything I've read about Petite Arvine says that the wines characteristically taste like grapefruits with a touch of salinity, but that wasn't my experience with these two bottles. While I wasn't a fan at all of the Swiss bottle, the Italian bottle was excellent and very enjoyable. The price is pretty high here, but the quality is too. I'd especially be interested in a more recent bottling from this producer, as I got the impression that this may have been starting to fade, though it wasn't dead yet.

Petite Arvine's origins are mysterious, but unfortunately that's all they are. The grape is thought to be native to Switzerland and one source claims that it has been grown in the Valais regions of Switzerland since 1602, while another source dates it to 1878. The 1878 date is important, as it is when the International Ampelographic Society met in Geneva and decided that Petite Arvine was a unique grape not found anywhere else in the Valais or in the world. It is this article that people point to when trying to establish a Swiss origin for the grape, but without knowing exactly how thorough their search was, it's hard to say how credible their statement is. The grape is also known today in the Valle d'Aosta of Italy and some source say that the grape is actually named for the Arve valley around Savoy where the grape is thought to have entered the Valais region, possibly from the Valle d'Aosta. In either case, the grape almost certainly has Alpine origins and today is found virtually nowhere other than the Valais and the Valle d'Aosta.

The grape's parentage is a mystery as well. Petite Arvine was thought to be closely related to Amigne for some time, but recent DNA testing has shown that they may not be that closely related after all. It does seem to be distantly related to Prié Blanc, Premetta and possibly Chasselas. The grape is commonly known as Arvine these days, though the Petite Arvine name was necessary for many years to differentiate it from another grape known as Grosse Arvine (or sometimes Arvine Grande) which has larger berries and which makes wine of a much lower quality. Today, Grosse Arvine is practically extinct (it does not exist in cultivation but only in grape collections) so the distinction isn't as important. The two grapes are related, but not as closely as their names might have you believe. Confusingly, both Arvine and Arvine Grande are synonyms for Silvaner, which is not related to either Petite Arvine or Grosse Arvine.

Viticulturally, Petite Arvine is a very late ripener, sometimes ripening a full month later than Chasselas. As a result, the vine needs a lot of sun to ensure that it gets completely ripe and it also needs to be protected from the wind as the clusters can be fragile. Wines made from the grape are highly esteemed, and though the Oxford Companion to Wine doesn't have much to say about Petite Arvine, it does say that it is "the finest of the grape specialties of Valais." Despite it's high critical esteem, Petite Arvine is not very widely grown, occupying only about 150 hectares of land in Switzerland, though this figure is up significantly from the 65 hectares planted in the year 2000. I couldn't find any numbers on the Italian acreage devoted to the grape, but you can be sure that it is extraordinarily small. Wines made from the grape run the gamut from bone dry to sticky sweet.

I was fortunate enough to find a bottle of Petite Arvine from both Switzerland and Italy. The first bottle I found was the 2007 Romain Papilloud Cave du Vieux Moulin Petite Arvine from the Vétroz region of Switzerland (home to our old friend Amigne). The wine came in a 500 mL bottle and I picked it up for about $39. In the glass, the wine was a fairly deep lemon gold color. The nose was very shy with a little bit of peaches and honey and something a little flowery, but it was mostly a blank and never really opened up. On the palate, the wine was medium bodied with fairly low acidity and was surprisingly dry. Given the size of the bottle, I was expecting something a little sweet, but this wasn't it. There were flavors of honeysuckle flower and under ripe peaches, but it was mostly metallic and hollow tasting. I don't say this very often, but this was an awful bottle of wine. It tasted like chemicals and was just bitter and mean. It was so bad, I was only able to get through one glass and had to pour the rest down the sink, which I almost never do. I don't know if this was just a bad bottle or if this wine always tastes this way, but for $39, I won't be running the experiment twice.

The second bottle that I picked up was the 2005 Grosjean Petite Arvine which I got from my friends at Curtis Liquors for about $30. In the glass the wine was a yellow gold color that was so vibrant it almost had a kind of neon tinge to it. The nose was very aromatic with ripe apple, butterscotch, pineapple tropical fruit, lees and a biscuitty, pastry-like kind of thing going on. On the palate, the wine was on the lighter side of medium with high acidity. There were flavors of ripe apple and pear, pastry dough, and a distinctive leesy, cheesy kind of flavor to it (the wine is fermented and held on its lees, which are stirred, for a month). I thought I was picking up some oak, but this wine is stainless steel fermented, so it was probably just from the lees contact. The wine not all that fleshy, but the flavors seem very decadent and rich. Nearly everything I've read about Petite Arvine says that the wines characteristically taste like grapefruits with a touch of salinity, but that wasn't my experience with these two bottles. While I wasn't a fan at all of the Swiss bottle, the Italian bottle was excellent and very enjoyable. The price is pretty high here, but the quality is too. I'd especially be interested in a more recent bottling from this producer, as I got the impression that this may have been starting to fade, though it wasn't dead yet.

Monday, December 5, 2011

Chambourcin - Lehigh Valley, Pennsylvania, USA

I first had wine made from the Chambourcin grape at an airport. Many years ago, the airport in Charlotte, NC used to have a tiny little wine bar tucked away in one of its darker corners that focused exclusively on wines made in the state of North Carolina. During a layover there one year when I was flying to visit my parents, my wife and I spotted it and since it was much less crowded than any of the other airport bars, we decided to give it a shot. I was fairly ignorant about wine at the time and was looking more for a drink than anything else.

The pourer was very nice and knowledgeable, but most importantly he was very patient. He was clearly used to people seeing North Carolina wines as a kind of novelty and he seemed determined to try and change that perception. The little wine bar offered several different flight options that covered a wide variety of styles made within the state, and I remembered being very impressed with many of the wines on offer. At the time, I knew just enough to know that North Carolina wasn't exactly a wine powerhouse, but I didn't know enough to be predisposed to the idea of North Carolina wine one way or the other, which it turns out is a pretty good way to discover an awful lot of things.

One of the wines that we enjoyed and ended up buying a bottles of was a Chambourcin. At the time, of course, I didn't know the different between Sangiovese and Sauvignon Blanc, and I had no idea that Chambourcin was anything other than a regular old wine grape. I always remembered it, though, as it made a very favorable impression on me at the time, and I was a little vexed that I couldn't find anything called Chambourcin at my local wine shops. Over time, as I became more experienced with wine, I started to understand that Chambourcin wasn't just any old grape, and today I'd like to tell you a little more about it.

Chambourcin is one of the French Hybrids, so called because, well, they were created in France. See, after phylloxera devastated the European vines in the mid 18th Century, the French were desperately trying to find some way to keep their wine industry afloat while combating the tiny louse. The major French agricultural research schools were devoting nearly all of their time and resources to understanding and defeating phylloxera, but many growers still had to earn a living, so they turned to Native American varieties as a stop-gap measure, since many of those grapes were naturally resistant to the louse. It turned out that the Native American grapes have a particular kind of aroma and taste derisively referred to as "foxiness" that the European palate could not adjust to, and it was quickly realized that pure Native American varieties were not going to be the long-term answer. Many private growers began to experiment with crossing the European vinifera varieties with these Native American species to see if perhaps they could breed some of the unwelcome flavors out while retaining many of the positive features of the grapes, such as their resistance to disease and their high levels of productivity.

Depending on your perspective, their results were either incredibly successful or incredibly dismaying. They did succeed in creating many different hybrid species that lacked the signature foxiness of their Native American forbears, but the resulting species were (and for the most part still are) still considered vastly inferior to their European forbears. The growers loved the hybrid grapes because they didn't have to spend as much money on pesticides and fungicides and the crops that the hybrids produced were heavy and profitable. The hybrids were especially popular in northern France where the climate is marginal for vinifera grapes for the most part, but where the hybrids and their cold-hardiness thrived. The French government wasn't too happy about it, as the booming hybrid production in northern France affected the prices for much of the bulk wine produced in southern France, and they decided to do something about it. In the 1950's and 60's, France outlawed the use of hybrids in any designated French wine, meaning that producers could not (and still cannot) even use the lowly vin de table designation for their wines with hybrid grapes in them. From a peak of nearly 1,000,000 acres of hybrids planted in France in 1958, the total has fallen to under 50,000 acres today.

Despite what many of them would have you believe, the French are not the only people on Earth who grow grapes and make wine, though, and many of the French hybrids are still in use today in European countries like Germany and the UK that have many areas that are too cold to reliably grow vinifera grapes. The hybrids also found a home in the United States in areas where the climactic conditions are too extreme for vinifera cultivation (namely, anywhere that isn't on the west coast). The criticisms of wines made from these grapes are still around and are still mostly salient, though, as the wines produced from them are never going to have the depth and complexity of the finest wines in the world, but growers and producers in many of these regions just don't have any other viable options. It's not just that vinifera grapes wouldn't fully ripen in many of these areas, it's that the climactic conditions may actually kill the vinifera vines, and it takes time and money to replant and regrow vines after they die. I'm not defending hybrids planted absolutely everywhere, but I am saying that they aren't absolute evil wherever they pop up, and if you run across one, approach it with an open mind and you may be surprised.

Chambourcin is one of the hybrids that it is worth taking a chance on. It is widely regarded as one of the better French hybrids, and it still is the third most planted grape in the Muscadet region of France (though I have no idea what they do with the grapes there). It was created in the 1860's by a French hybridizer named Joannes Seyve who must not have kept very good records, as the grape's exact parentage is a mystery (it is thought to be a crossing between a Seibel crossing and another of Joannes Seyve's hybrids, but this far removed from the process, it is virtually impossible to say with any certainty). It is also known as "Joannes Seyve 26-205," but some official French body changed it to the much snappier Chambourcin. It was not commercially available until 1963, for some reasonIt has a fairly long growing season and isn't as cold hardy as many of the hybrids are, so it tends to be planted in warmer areas.

The wine bar in the Charlotte airport closed a year or two after I first discovered it, and I don't trust my notes on the wine I had to be of any value at this point in time, so unfortunately I won't be writing about that experience. A few years later, though, I was visiting my sister in law in Philadelphia and I wandered into the Clover Hill Winery shop in the King of Prussia mall (which has also, sadly, closed, though the winery is still in business). I was very excited to see that they made a Chambourcin, so I picked up their 2008 offering for about $15. In the glass, the wine was a deep purple-ruby color that was opaque nearly all the way out to the rim (Chambourcin is well-known for its deeply colored wines). The nose was nicely aromatic with black cherry, spice box, blackberry and toasty vanilla notes. It had a lot of oak character to it, which had me a little on edge at this point. On the palate, the wine was medium bodied with fairly high acid and low tannins. There were tart blackberry, sour cherry and raspberry flavors with some baking spice, charcoal and smoke. The wine was very tart and surprisingly thin, and the oak influence was very noticeable. Overall, it was clunky and out of balance, I thought, and needed more weight on the palate to carry the oak that it was richly covered in. It had a good amount of complexity, but ultimately was just an OK wine. There are much better examples of this grape out there, and I'd encourage you to visit your local winery and see if they are doing anything with this grape. Even if they aren't, visit your local winery anyway and discover what kind of treasures your backyard may have to offer.

The pourer was very nice and knowledgeable, but most importantly he was very patient. He was clearly used to people seeing North Carolina wines as a kind of novelty and he seemed determined to try and change that perception. The little wine bar offered several different flight options that covered a wide variety of styles made within the state, and I remembered being very impressed with many of the wines on offer. At the time, I knew just enough to know that North Carolina wasn't exactly a wine powerhouse, but I didn't know enough to be predisposed to the idea of North Carolina wine one way or the other, which it turns out is a pretty good way to discover an awful lot of things.

One of the wines that we enjoyed and ended up buying a bottles of was a Chambourcin. At the time, of course, I didn't know the different between Sangiovese and Sauvignon Blanc, and I had no idea that Chambourcin was anything other than a regular old wine grape. I always remembered it, though, as it made a very favorable impression on me at the time, and I was a little vexed that I couldn't find anything called Chambourcin at my local wine shops. Over time, as I became more experienced with wine, I started to understand that Chambourcin wasn't just any old grape, and today I'd like to tell you a little more about it.

Chambourcin is one of the French Hybrids, so called because, well, they were created in France. See, after phylloxera devastated the European vines in the mid 18th Century, the French were desperately trying to find some way to keep their wine industry afloat while combating the tiny louse. The major French agricultural research schools were devoting nearly all of their time and resources to understanding and defeating phylloxera, but many growers still had to earn a living, so they turned to Native American varieties as a stop-gap measure, since many of those grapes were naturally resistant to the louse. It turned out that the Native American grapes have a particular kind of aroma and taste derisively referred to as "foxiness" that the European palate could not adjust to, and it was quickly realized that pure Native American varieties were not going to be the long-term answer. Many private growers began to experiment with crossing the European vinifera varieties with these Native American species to see if perhaps they could breed some of the unwelcome flavors out while retaining many of the positive features of the grapes, such as their resistance to disease and their high levels of productivity.